There’s a fine line between hoarder and archivist—but Brian Kelley just about sits in the second camp. From maps to discarded MetroCards, the New York photographer and collector may own a fair bit of ‘old tat’, but rather than stash it all away in shoeboxes gathering dust, he lets it out into the world.

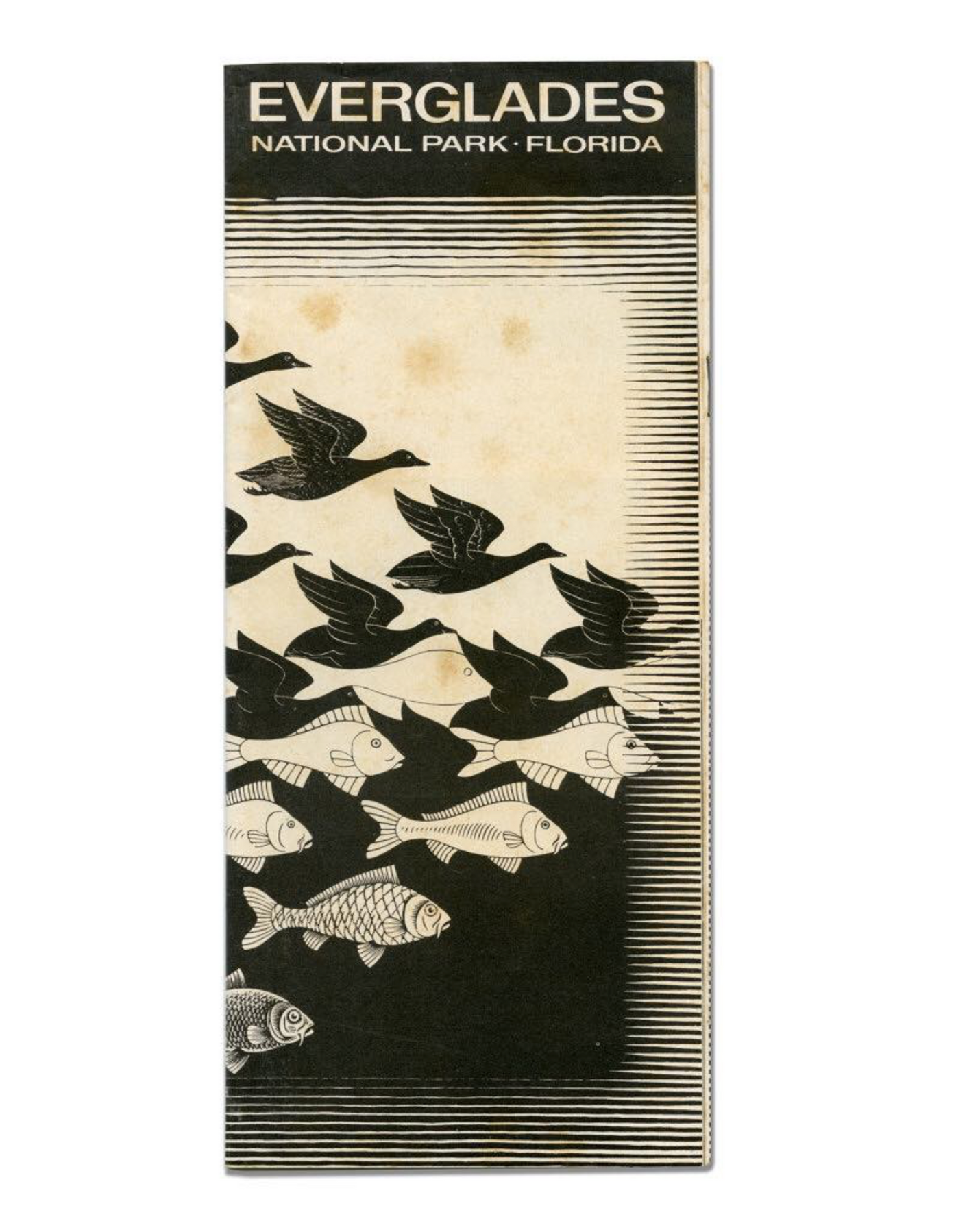

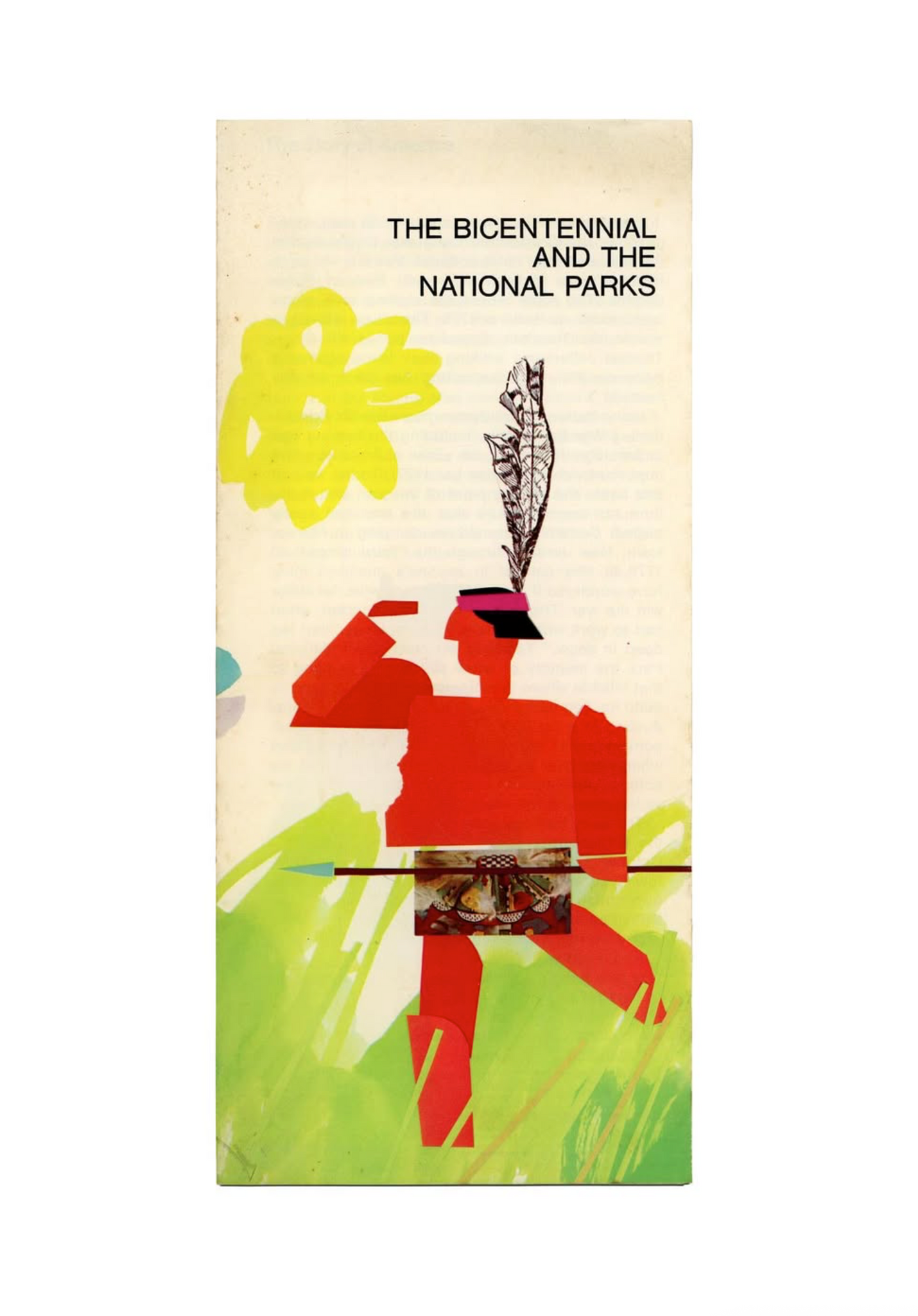

Published by Standards Manual, the two part Parks series is a true treasure-trove of outdoor ephemera, displaying Kelley’s extensive collection of National Park Service maps and brochures—documenting not just the visual history of the US National Park Service, but the evolution of graphic design and the printed page across the 20th century.

His Gathering Growth project applies the same thorough process to photography—as he lugs around a large-format camera into ancient woodland on the endless search for the biggest and oldest trees in the United States. After all, if a tree grows really tall in the woods and no one is around to take high-quality photographs of it, is it even really that tall?

Here’s an interview with the man himself about old maps, big ol’ trees and the buzz of going where no one has gone before…

Sam: Your Parks books collect together maps and ephemera from the U.S. National Parks Service. How did this project start? You must have quite a collection now.

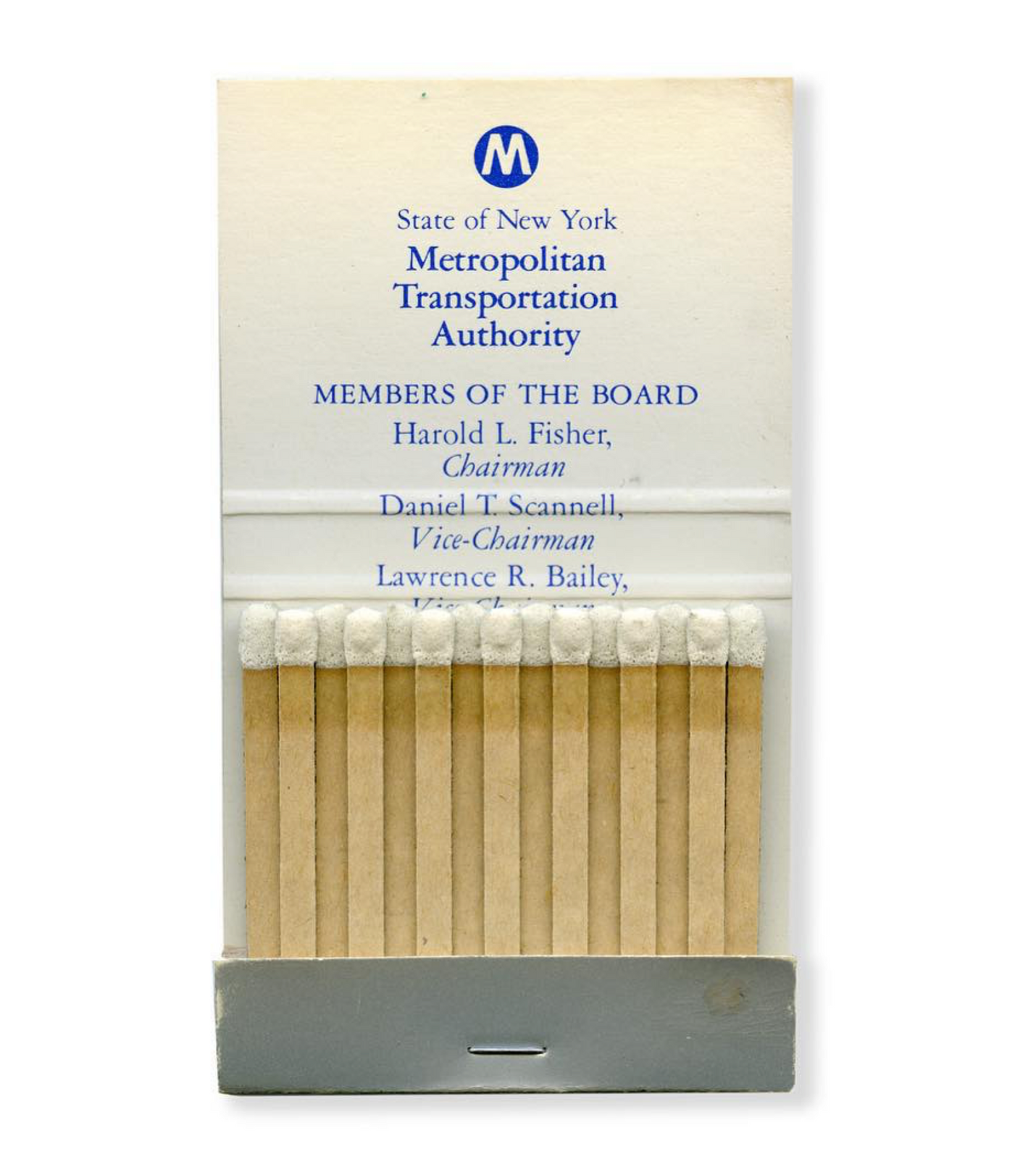

Brian: I’d just wrapped up my first book with the publisher Standards Manual—New York City Transit Authority: Objects. We finished that and they were like, “What else do you got? What else do you want to make?”

At that time, I wasn't collecting anything else, but I just started doing deep dives into the internet, and eventually, through eBay, I found this whole plethora of amazingly well-designed National Park brochures. I basically screenshot it and I bought a few and I sent them over to the publisher, and they were like, “You’re onto something, keep going.” Three years later, we had Parks. And then for Parks 2, there were maybe three or four more years of collecting.

Sam: And what was the process of collecting? Was it just a case of just scouring eBay constantly? Is this stuff expensive?

Brian: Every single map is from eBay. Every once in a while, I would get maps that were maybe like $24. I feel like for Parks 1, $24 to $40 was probably the most I paid for a single map, but I do feel like once Parks 1 came out, the process of making Parks 2 was way harder.

Sam: I suppose when you start collecting something, everything’s new. But once you get that low-hanging fruit, those rarer bits are a lot harder to find. The game gets tougher.

Brian: Yeah—that's why it took us another four or five years. Essentially, I had already gotten a lot of good ones, and in order to keep that same quality, I knew what I needed to get. And you're just at the whim of whatever collectors or people trying to sell off their parents' archives have got.

A lot of times when I would communicate with people on the internet or through eBay, they'd be like, “Oh yeah, my dad passed away, and he loved traveling. In the 60s and 70s, he traveled all around the country.”

I talked about this in the introduction to Parks 1, but I think when you just look at a single map, it might not mean anything. But then once you start putting them together like an archive or a collection, that's when they start to feel like they have real weight or value.

Sam: Yeah—that’s when you can start to notice patterns or themes.

Brian: Especially once I started to look at the 60s and 70s maps. That’s my favourite era. The design in that time was just so loose, but so well considered versus today, where it's just some guys typing into a template and pressing print.

Sam: I’ve noticed that a lot with printed stuff. Even with really dull things like church newsletters, there’s an era where they were inadvertently amazing to look at. Maybe desktop publishing and digital printing kind of put an end to that. Why does the 60s and 70s stuff stand out to you?

Brian: It's the design, the type, even the photography—they were doing a lot of macro shots of plants or bugs, and then laying beautiful type over those photographs and it just looked beautiful. But I will say that the printing costs were crazy, which is one of the reasons why they went to the standardized format that Massimo Vignelli designed. But up until then, from like the ‘50s until the early 80s, everyone was just doing their thing.

There are some graphic or design consistencies, and you can sometimes tell that the same designer or agency did different maps, but generally they’re so loose.

Sam: And then this Massimo Vignelli guy came along. Can you explain what he did?

Brian: In the late ‘70s he basically came in and created their standards guide—he created what's called the Unigrid. Everything we see today is based off of the Unigrid, even though it's so horrible now. I was good up until like ‘92, and then after that, for whatever reason, people started just like doing whatever they wanted. If you really look at a 1979 brochure compared to a 2010 brochure, it's very obvious that they just stopped following. It's kind of sad, honestly.

Sam: It’s interesting, because maps are pretty basic, functional things—but then for whatever reason those designers in the 60s and 70s added these wild graphic flourishes. They didn’t really need to be so amazing.

Brian: I think that was just the time—you know, drugs were flying and people were having fun. Looking from the official formation of the National Park in 1916 to present day, these maps follow not just the evolution of design, but the evolution of photography. So you have this super romantic gothic type with beautiful black and white photography, and then you look at that transition to the present day.

Sam: How many of these things were they getting printed?

Brian: I'm not sure. I would think that maybe I would see more on eBay, but there’s some brochures I’ve only seen once. And there's times I've gotten into bidding wars with people and a brochure has gone up to almost $250 because no one's ever seen it before.

Sam: And how long were they in print for? Was it like, “This will be good for like eight years and then we have to re-update it?”

Brian: I’m not absolutely sure, but I feel like maybe every four to five years they’d switch it out, unless there was major stuff changing. In the book you can see side-by-side from one year to the next when Mount McKinley changed to Denali. So when they changed the name of the National Park, they had to get the maps changed ASAP.

Sam: Quick turnaround needed there. Going back in time a little, what was the process for your New York Transit book? Was that a similar thing of just hunting around the internet?

Brian: I was 22 years old and, basically, I started wanting to experiment. I’m a still life photographer and I was wanting to do a new project. And at the same time, a lot of people were doing these perfectly laid out grids of items.

Sam: Oh yeah—the ‘Everyday Carry’ thing—a Macbook, a Moleskine and a huge hunting knife.

Yeah. And so I was like, “Oh, let me try one with MetroCards.” I walked around the MetroCard station just collecting all these different MetroCards. And then my brother was like, “Oh, have you checked eBay? There's probably some crazy old ones or rare ones.” And then I just kept going—finding tickets from 1905, and then belt buckles and maps. And that was the first time I realized, like, “Damn, this is addicting.”

Sam: Is this stuff organized? Have you got nice shelves and drawers and stuff, or is it just chaos?

Brian: It's in horizontal filing cabinets. But, you know, I live in a cabin in upstate New York, so I'm limited in space and storage. The goal is eventually to be able to sell it to a museum that would be interested in housing it as a permanent collection.

Sam: I can’t imagine anyone else has an archive of this stuff to such a degree. Even the NYC Transit Authority or the National Park Service.

Brian: I don’t think people have the foresight to hold on to stuff. You just don’t know the value of something until all of a sudden it’s been 10 or 15 years and it’s like, “Damn, we made a lot of shit!” And it’s hard because archiving is so difficult—and even if you get a system, if you eventually transition to something else, then you have to go back and redo everything. It’s a constant project.

Sam: I suppose you having these collections, it kind of gives you an excuse for hoarding.

Brian: Well, that's the thing. I feel like there’s a really fine line between being a collector, archivist and a hoarder.

Sam: Where do you sit on the line?

Brian: You have to make a project out of it. I feel like you really have to display it or sell it on eBay or make a book out of it before it gets to just becoming you holding onto stuff.

Sam: “I swear it's for the good of humanity!” Do you think being a photographer and then a collector kind of go hand in hand? Photography is a kind of collecting, isn’t it?

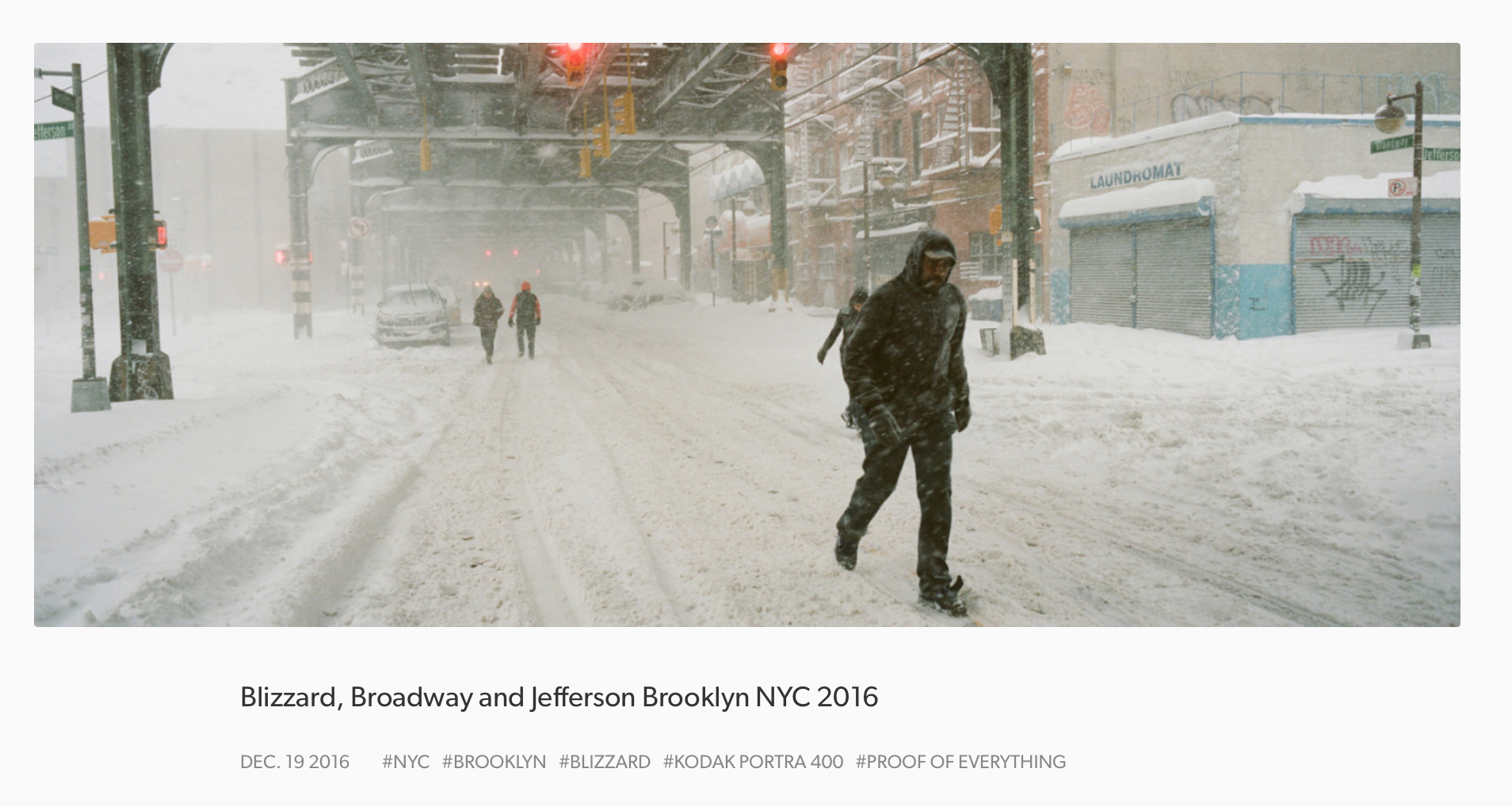

Brian: I don't know if you've ever heard of this fashion photographer who called himself the Sartorialist? He was just going down and photographing people on the streets and all that kind of thing. I remember he had this quote that really stuck with me, “Every photographer has a hidden obligation to archive the world around them.”

That's perfect. And I think honestly that might have been one of the initial kickoffs in my head to think about photography more than just taking photos of a moment in time and space and to think about the big picture.

Sam: The difference between aimlessly shooting photos, and thinking, “I’m going to take photos of all the phone-boxes before they’re taken away.”

Brian: Yeah, absolutely. I had another blog called Proofofeverything for a little while that was like the ever changing New York City. It was just me going around with a point and shoot and taking photos, but it was very specific to showing how fast New York City was changing. And if you weren't documenting it, you'd miss it.

Sam: I bet if you went to those places now, they’d look different—like a lamp-post would have moved or there’d be scaffolding. Tell me about Gathering Growth. That’s another pretty large scale project.

Brian: That was basically just me being in New York City, doing the same thing every single day. I was working at a brand and I was just like, “Man, I want to do something different. I want to do something bigger.”

And then just before I set off on a trip, my friend told me to read this New York Times article, ‘Robert Frank, the Man who Saw America’. And that really inspiring—him living out of a car for two or three years, contributing to history through this book, The Americans.

So when I came back off that trip, I bought a used car in Brooklyn, took two months off work and traveled around the country with a friend. That’s when I got up to the Pacific Northwest and found big trees for the first time. They just changed my life. When I came back I was just digging through the internet, trying to find more archives—and that was the thing—there weren't really that many archives of all these big old trees.

And then eventually I found out about American Forests, this organization where they go around the country documenting the oldest trees. They started this thing in 1940 called the Champion Tree Program, which uses this point system to determine the biggest trees in America. They had no real archive other than the information, so I pitched to them. I was like, “I want to travel around the country and photograph trees—is this like a job you guys have?”

They were like, “No, but we would love for you to do it.” And then I was able to get funding privately so I bought a transit van and built it out with a friend. I lived out that for three years, travelling around the country and then eventually started Gathering Growth Foundation. And now I'm currently working on our first book, which is The Oldest and Largest Trees of New York State.

Sam: Is there a big scene around these big trees? Is it like storm chasers? What kind of people like to hunt these big trees?

Brian: I would say most of us are probably a little introverted and just want to be in the woods. I think that being around these trees that are over 2,000 years old puts your own life in perspective, and makes you think twice about your place on the planet. I really just felt gravitated towards being around these things and spending time in these old growth forests.

You have a good chance of being somewhere that no one has ever stepped foot before, and that’s a really cool feeling that I constantly search for.

When you’re in an old growth forest, it can be so quiet—you’re just going, going, going and then all of a sudden you turn to your left, you come around this ridgeline and there's something that has been growing for 500 to 800 years. You can go around and look at this thing that nobody has seen for a very, very long time. It’s so sick.

Sam: Is that almost like an in-built human thing? We all want to find something new or different or unique.

Brian: I don't know. I'm trying to think of the right words for it. I think most humans by nature are curious, you know? We’re constantly wondering what’s around the corner.

Sam: From the trees to your photography to your collections, is there a through line that runs through it all?

Brian: I'm not trying to come off cocky at all, but I pride myself on quality—wanting to always make sure that everything is done at the best quality—whether I’m photographing something or scanning a map.

Sam: You give these things the quality they deserve. Weak, throwaway photos of those old trees maybe wouldn’t do them justice.

I'm not saying that every photograph I take of a tree is good by any means—I will be the first to admit that I hate 80% of the images I take—but if you take a shitty photo of somewhere and try to convince somebody that it’s is a special place that they need to visit or we need to save—people might not care about it.

If somebody doesn't have the ability to go physically somewhere then you have to bring that same feeling that you felt there to them via photo or video. I think that's an approach I try to take with all my archives—trying to make things look the best they can.

It’s hard to make people care about something they can’t see. If you lived in West Virginia your whole life and they're like, “Oh, we're gonna log this section of the Sierra Nevadas” And maybe this bill comes up and they're proposing the logging, but people that haven't been there might not think twice about it—but if you have been there and you’ve experienced it, you’ll think, “I love this place—I can't believe they're gonna do this.” And then you might take action.

And that can all start with taking good photos of a place to share to people to inspire them to go and visit them. That's why in 1916, going back to the National Park, they put out this map collection together—it was literally made to sell Congress on the idea to preserve the National Parks, right? It was a portfolio for the National Parks.

Sam: Sort of like, “Look how good this is!”

Brian: Yeah—they were filled with beautiful black and white images of light streaking through the giant sequoias—they were epic. Those images were seen by people who lived in Washington DC who’d never even seen any of this stuff before, who were like “This exists? Yeah, we have to protect it.”

Sam: That brings me nicely to my last question… how do you take a good photo of a tree. I see photos of trees and nature all the time that look pretty uninspiring—how do you make a tree look amazing?

Brian: I feel like unfortunately, a lot of people react the most to when you put a person in that photo. You could photograph the biggest tree in the world, but unless you have something there for scale it’s hard to see how big it is. As soon as you put a human in there people are like, “Oh damn, that's crazy.” They did that a lot in those National Park portfolios—whether it was with epic mountains or the giant sequoias.

Sam: As soon as you’ve got a guy in a flannel shirt standing next to it, you know it's not a bonsai tree.

Brian: Yeah—I think that’s how you can have the most impact—you’ve got to give people some sort of inspiration.