Some great photographers turn their hand to making films, and occasionally a famous musician might sell a few paintings, but even now—in today’s age of endless multitudes—it’s rare for someone to be a true pioneer in two completely different fields at the same time. Arlene Blum is a bit of an exception.

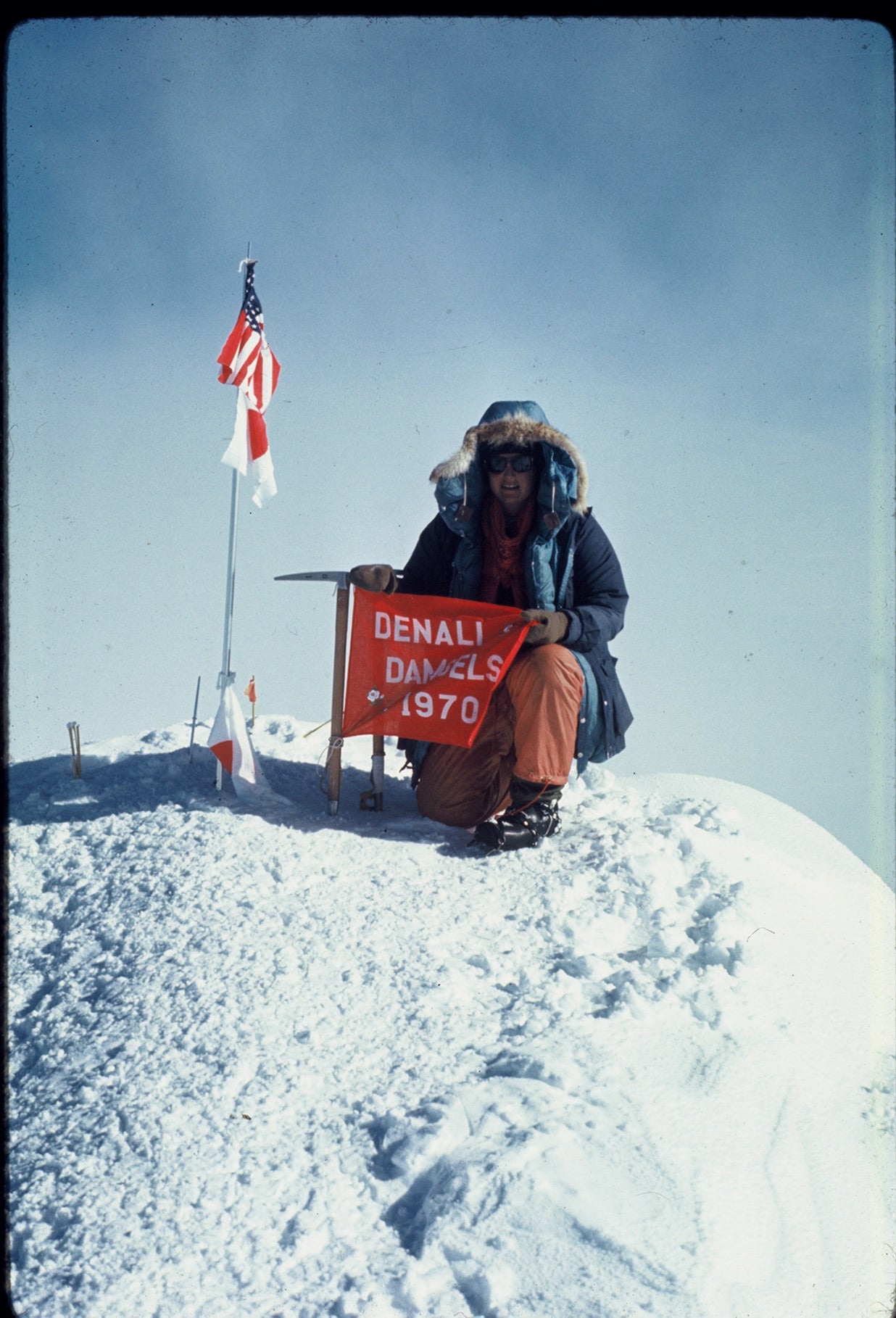

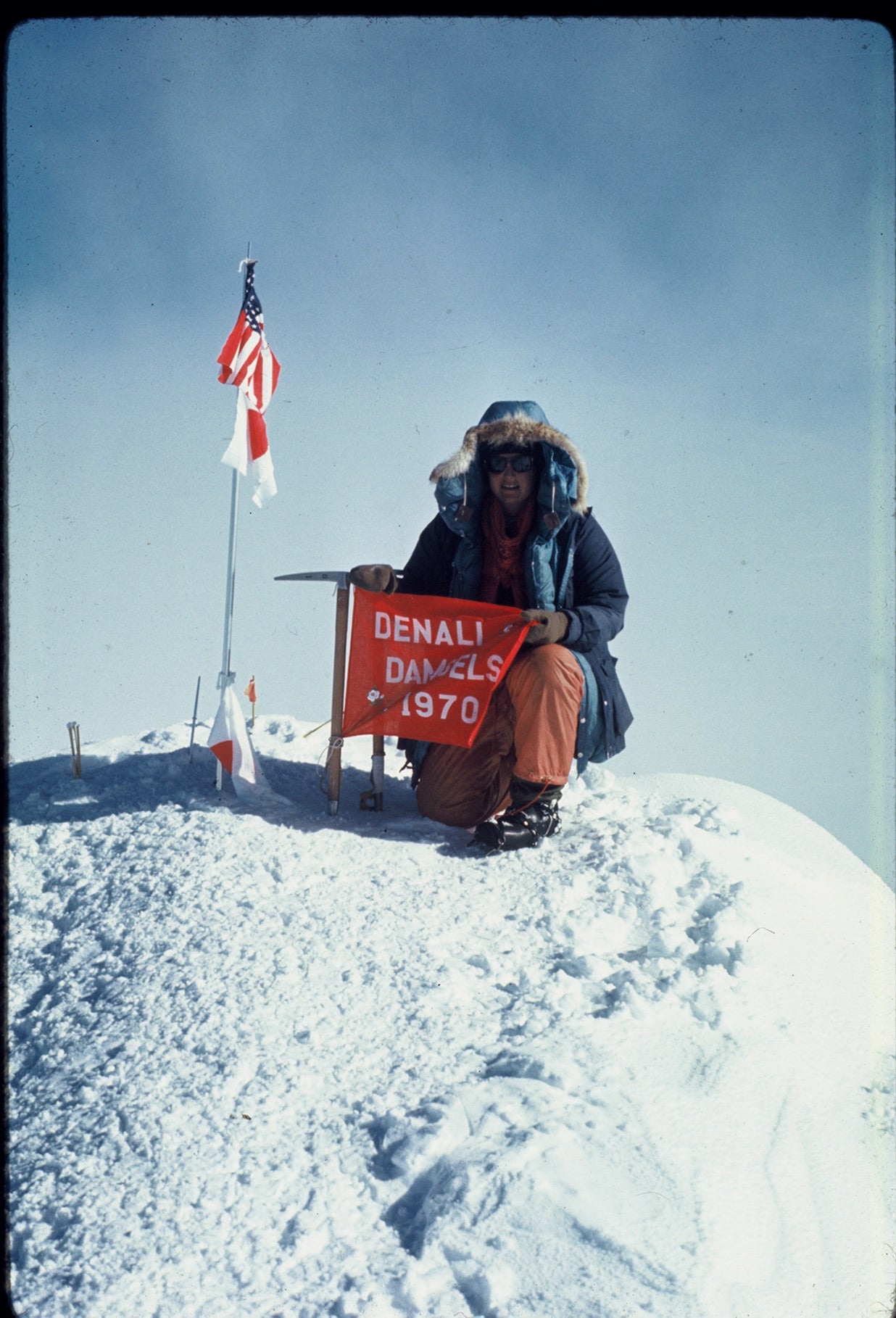

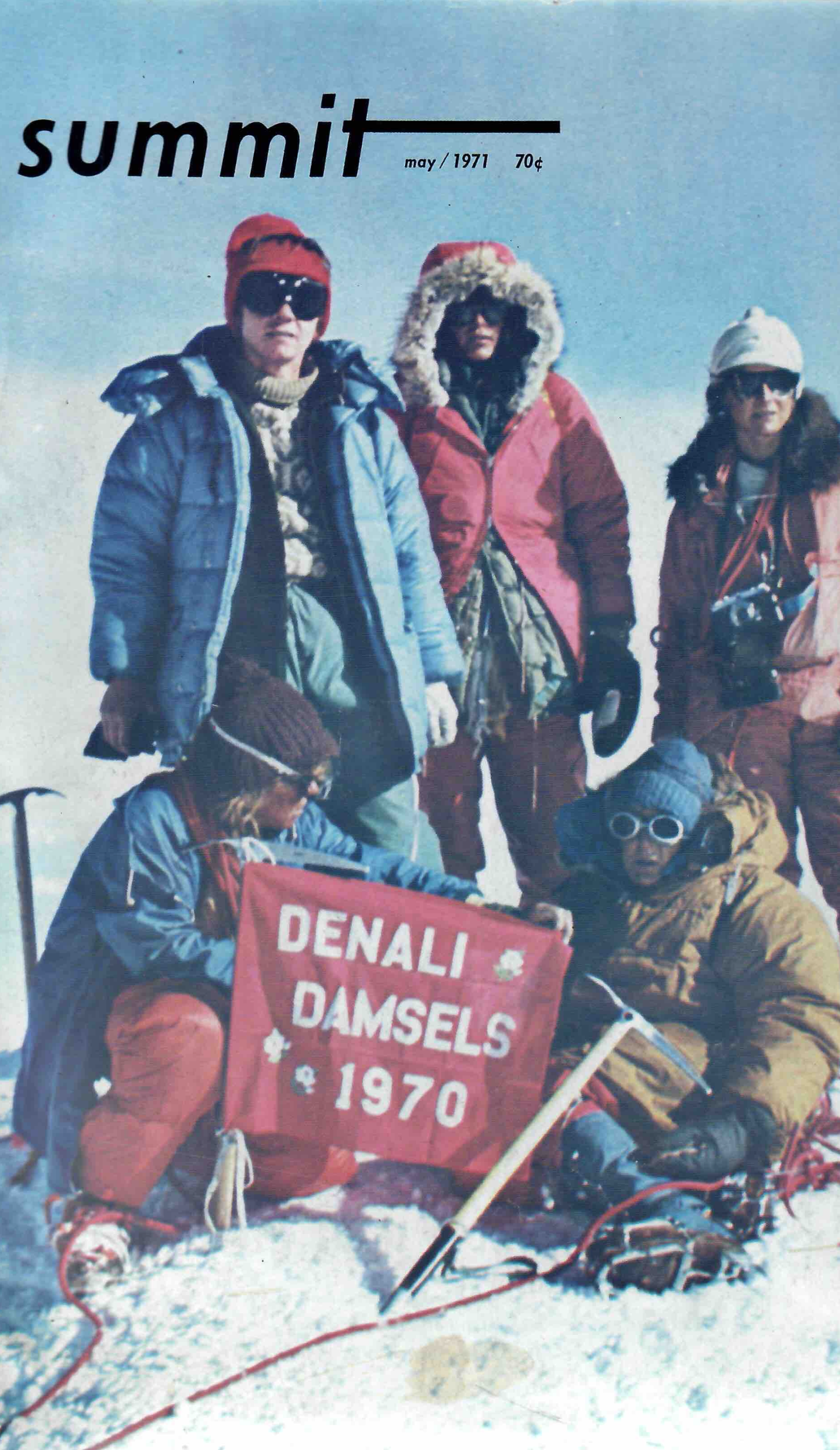

Firstly, and perhaps more relevantly for this here website, she’s a pioneer of mountaineering, leading expeditions up some of the most notorious peaks this planet has to offer—from the first American ascent up Annapurna in 1978 to the first all-female ascent of Denali in 1970.

Secondly—and perhaps more importantly as far as the ol’ human race is concerned—she’s a pioneer in environmental health, and in 1977 she published a groundbreaking paper which helped wipe out the usage of cancer-causing chemicals in children’s pyjamas.

Seemingly undeterred by the concept of the impossible, she’s pushed past countless boundaries in search of a better world—and is still going today, fighting for safer chemicals as founder of the Green Science Policy Institute, all the while clocking serious miles out on the trail.

Yep—quite the pioneer—which is why very early one Saturday morning I sat in my parked car, fired up the trusty Dictaphone and called up her house in Berkeley…

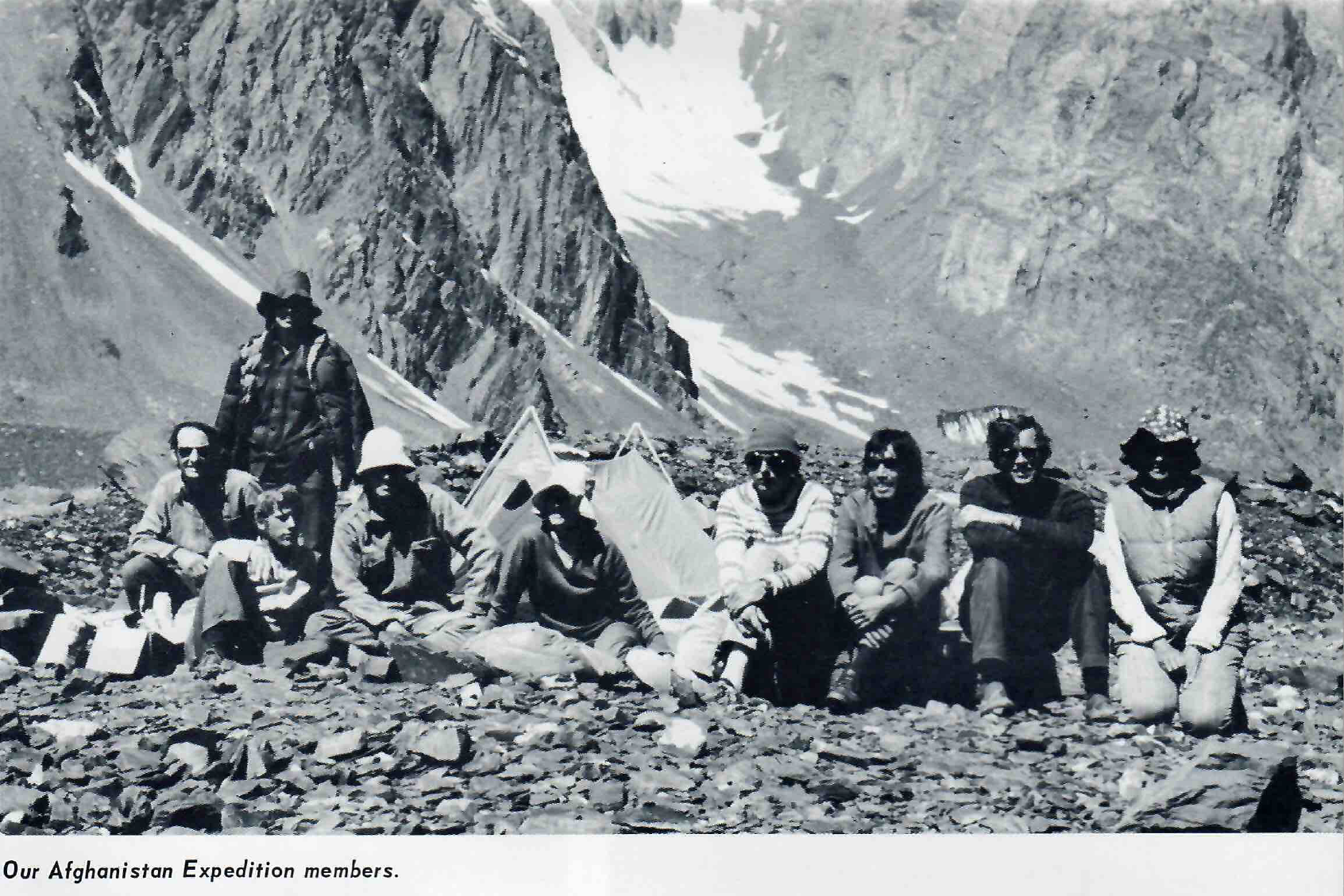

(All photos in this article are copywrite to Arlene Blum)

Sam: From reading about your life it seems like there’s a theme of going against the grain—whether you’re pioneering all-women expeditions or working to change government safety standards and cut out harmful chemicals. Would you agree with that?

Arelene: The way I think of it is that I get pictures in my mind that need to happen to make the world better, and I find other people to share the vision, and then we all work together—whether that’s climbing a mountain or changing a bad flammability standard, it’s quite similar.

Sam: What about when you started climbing in the 60s? Whilst a lot of people in that era climbed and hiked, not many took it to the level you did. What do you think it was that set you apart, even then?

Arlene: Curiosity. I wanted to travel and go to new places—I always wanted to know what was on the other side of the mountain. I think it was that thing about getting a picture in my mind. I really liked climbing, and I wanted to go on expeditions, but at that time women didn’t get chances to do that, so I thought, ‘I wonder if a group of women could climb that mountain?’ It’s about curiosity, and seeing what you can do.

Sam: Was that ‘women can’t do this’ attitude around mountaineering expeditions back then almost like a challenge?

Arlene: Yeah—or maybe it was more like what I’m doing in science now. Most of the things I do seem impossible, but I’m not doing them because of that—I’m doing them because they seem worthwhile. The fact that people say they’re impossible doesn’t stop me from trying them. Once I get that picture in my mind, I have trouble not following up on it.

Sam: I get the idea that a lot of people would like to try things, but are often held back, thinking things like, “How could someone like me do that?” How do you get past that?

Arlene: I don’t know. I guess I’ve always done what I wanted to do—and found other people who wanted to do that too. You have a vision, then you find people who share that vision, then you make a plan, and you might not know what’s going to happen, but you have an adventure, and you discover things along the way.

Sam: What were the attitudes to female climbers back when you were first going on expeditions in the early 70s?

Arlene: At first I felt really lucky. I started climbing in college—and there I wasn’t up against anything. I’d climb, and no one thought it was at all unusual—so I found it empowering. When people said that women couldn’t climb, I just thought, “What’s wrong with them?” I always felt I could climb, and other women could. But it was hard to get invited on expeditions.

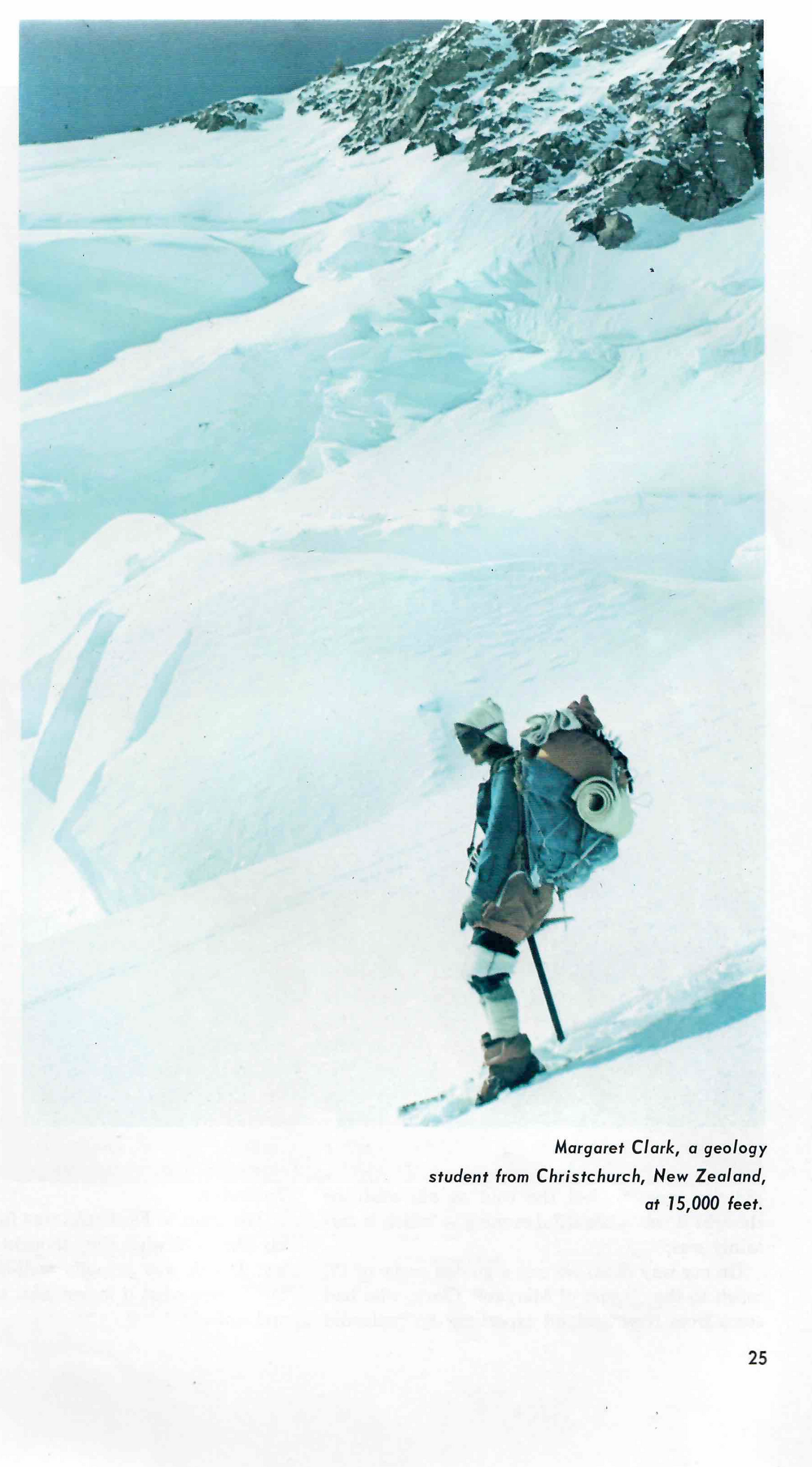

Denali was my first women’s expedition. I got inspired because my climbing friends were all going on a guided trip to Denali, and the guide said women could only go as far as base camp for a reduced fee, and help with the cooking, but they couldn’t try to climb the mountain. I’d already climbed higher than Denali in the Andes—so I figured that women could climb it. So I ended up organising a women’s team to climb Denali, a long time ago back in 1970. We were the first women’s team to climb Denali.

Sam: How did it go?

Arlene: We did it, but it was extremely challenging because the woman who was our leader—who was a very experienced Alaskan climber—it turned out she was not good at altitude and had severe issues. She collapsed unconscious right below the summit. I was the deputy leader—I was 25—and I ended up taking over and we got her down alive. So that was a big step in my confidence and my career.

Sam: Was that a bit of a turning point for these kinds of expeditions—showing the mountaineering community that women could climb high mountains?

Arlene: I don’t think anybody paid that much attention to it, because it was so early. But then ten years later I read in the paper about the first women’s team attempting to climb Denali… ten years after we had climbed it. We were too soon! People didn’t notice. But personally, it was empowering for me.

Sam: Was that what then led to the Annapurna expedition? Thinking, “We did Denali, can we do something bigger?”

Arlene: Actually after Denali in 1970, I was finishing my doctorate and I saw a movie called The Endless Summer—it’s a surf film where the surfers go around the world looking for the perfect wave—and I decided I would go around the world looking for the perfect mountain.

Again, I had a picture in my mind of a round the world mountain climbing trip for about a year and a half… and I did that. So I looked for people who’d do it with me—asking people if they’d want to climb with me—and a few did. We made first ascents in the Himalayas, we climbed nearly all the peaks in the Rwenzori on the equator in Uganda, we did a technical climb on Mount Kenya and climbed about seven thousand metres in Afghanistan. We got a lot of expedition experience during the ‘Endless Winter’—it was like ten consecutive expeditions.

Sam: How did you plot something like that out back in the 70s? That seems like quite a logistical feat.

Arlene: I got a book about the world’s mountains, and figured it all out from there. I didn’t have much money—I think we had $200 a month for travel and sherpas and everything we needed. So we were very frugal, but apart from not doing the Carstensz Pyramid in New Guinea because we couldn’t get permission, I think we managed to do everything that I planned. So that was another example of planning something, then finding people, then doing it.

In Afghanistan at about 7000 metres, the idea for Annapurna came up. We were on a base camp with some Polish climbers—and Poles are some of the best high altitude climbers. There was a Polish climber called Wanda Rutkiewicz—the third woman to climb Everest, and the first woman to climb K2. Anyway—this was before she’d climbed any 8000 ft peaks. She was coming down this mountain, and we were going up, and we said, “Let's climb Annapurna together—all women!” That was 1972, and we didn’t go there until 1978.

Sam: How did you gear up for that?

Arlene: Well, in ’76 I was on the second American Everest expedition. There were two women on that expedition, so we were the first American women to have a chance to climb Everest. I learned a lot about organising expeditions there, and having done the women’s Denali expedition—which was really tough—I realised that women could climb really high mountains, it was just that they didn’t really get much of a chance. So when I was in Kathmandu after Everest I went to the Ministry of Tourism and got a permit for Annapurna. So I had two years to organise the trip, raise the money and find a team.

Sam: How did you raise the money? I imagine a trip like that was expensive.

Arlene: We put the word out for women climbers—and there weren’t that many at that time. We had a t-shirt made which said ‘A Woman’s Place is On Top… Annapurna’. We still sell them now on my website! And the same guy still makes them! Our budget was $80,000, and we raised most of that by selling t-shirts. It was quite crazy, but it worked.

Sam: And then after all that—what was the feeling of actually getting there and setting off?

Arlene: It was wonderful to be there on this big adventure. There were a number of British and Scottish women who would drive their Land Rovers overland to Nepal to go climbing even back in the 50s, but even for us in the 70s, it still felt like an unknown adventure.

Annapurna is considered the most dangerous, and possibly the most difficult, of the highest Himalayan peaks—which we didn’t realise at the time. That’s because of the high precipitation. It’s pretty frightening to be around so many avalanches, but it’s very beautiful.

Sam: What was a normal day like there? Did you have a routine?

Arlene: It depended what camp you were at. When we were very high up, we’d have to get snow and melt it for water. So we’d get up pretty early to melt snow and cook breakfast, before packing our gear and towing our loads up to the next point. It was melting, cooking, packing and carrying—and then coming back down. This was an old style expedition where we were carrying a lot of equipment. Nowadays people don’t do things the way we did—they climb alpine style, a lot faster and lighter.

Sam: There was quite a kickback after the expedition—with people saying the expedition shouldn’t have happened—how did you react to that?

Arlene: Two of our team fell to their deaths, and that was super hard for everybody as they were our dear friends. So it was devastating on people—it was such a major experience that many of our own personal relationships kind of broke down—it was so stressful.

When we’d climbed Everest we’d had about 30 sherpas and several hundred porters helping us and nobody said that Americans hadn’t climbed Everest. But on Annapurna we had five sherpas helping us, and people were saying, “Well, it wasn’t really women who climbed it, because there were sherpas there too.” So that didn’t really seem fair.

Two years later I organised a women’s expedition without sherpas or porters to a mountain called Bhrigupanth which is in the Indian Himalayas next to Meru. We did the first ascent on our own—and I wanted to do that without sherpas to see if we could do it ourselves.

Sam: And around the time of these expeditions, you were working on the paper which led to removing dangerous chemicals from children’s pyjamas. Where does that fit in this timeline?

Arlene: I discovered it before I went to Everest. I couldn’t decide whether to write the paper, or go to Everest. In the end I decided I’d do both—go to Everest and keep writing. I actually finished writing the paper on the mountain, and sent it by mail-runner back to Kathmandu. We climbed the mountain in October of 1976, and the article was published in the journal Science in January of 1977.

Sam: What happens when an important paper like that is released? How long is it until something happens?

Arlene: Well, the paper got released, and then like we do now, we did a lot of communication and media. In those days there were three TV networks in the US, and we spoke on the morning show on all three of them, and then every parent in America knew that their kids had toxic flame retardants in their clothes. And three months later, the flame retardant childrens’ clothing was no longer allowed. That’s how things worked in the 70s… now it takes a lot longer.

Sam: Did the two things—mountaineering and science—feed into each other? Were there certain aspects from one you could use in the other?

Arlene: Yeah—with the advantage of time I can see the similarities. With science, I’d come up with ideas that other people thought were improbable, and then persevere to do things that hadn’t been done—and I suppose that was similar to mountaineering. I had a really protective childhood where I wasn’t allowed to do anything like go to the beach or take horseback riding lessons, so I’d persevere to figure out a way to do them. I think I’d learned about that from a very early age.

Right now, with my scientific and policy work, we’ve got three projects which all seem kind of impossible, but if we’re successful we’re going to reduce harmful chemicals for everybody—so it's really important. It’s so challenging that hardly anyone else is working on it, but we’ve been successful on a few projects already like that which had seemed impossible.

I guess when someone says things are impossible, I still think that if it’s worthwhile, then it’s worth trying—there’s got to be a way. One example is that all the furniture in the USA and Canada contained these harmful flame retardant chemicals, and we were able to stop that. And that was really hard, but it was possible. Now we’re trying to do the same thing to stop the use of harmful flame retardants in cars, and that’s really hard, but it's so worthwhile that we want to do our best.

Front Covers of Summit Journal magazines containing Arlene Blum Articles.

Sam: It seems like you set yourself some hard challenges. Do you almost thrive off these seemingly impossible tasks?

Arlene: I like goals. I try to walk 15,000 steps a day, for example. And that’s challenging, because I work so much of the rest of the time. So during meetings I’ll be walking. And I really like to cross-country ski, but I can’t take off that much time from work, so I figure out ways to combine them. I’ll ski in places where there’s connectivity—so I can do interviews and have meetings whilst I ski. That takes a lot of organisation to coordinate—but because I set this goal, then I’ll work hard to do it.

If I hadn’t had my steps today, then I might be walking right now in the dark—but I ended up getting plenty of steps so I’m taking it easy now. I guess I just set an objective, then I try to achieve it. I always say that I never have any self-discipline—it’s not discipline, it’s curiosity, wanting to do things, and having goals.

Sam: How have you managed to keep going doing all this? A lot of people wind down by their 30s, never mind their 70s…

Arlene: I think part of it is the luck of your genes—but also getting those 15,000 steps a day is really good for my mind and body. I live in the Berkeley hills, which is really beautiful for hiking. So although I work really hard, after work I’ll spend two hours hiking in the hills.

Sam: How far is 15,000 steps? I’m trying to equate that to miles.

Arlene: I don’t know. After work I walk for about two hours and I get 8,000 steps there. So it’s about four hours of walking a day at my slow pace.

Sam: That’s good going. I suppose it’s late for you now in California so I’ll try and wrap this up a bit. Looking back on all this, what stands out? Are there any quiet moments that really stick with you?

Arlene: Walking across the Himalayas was one of my favourite adventurers. Walking through Nepal, there were trails all the way because they never made any roads in the mountains, but then we came to India. Because the British had conquered India they had put roads into the mountains. That meant that people tended to take the roads and there weren’t very good trails—so we were walking on these very bad trails, always getting lost.

It was a snowy spring, and I remember once we were lost in a blizzard and we couldn’t find our path, but then four yaks came by—we had no idea where they came from. There was nobody with them, it was just four yaks marching making a good trail, through the very deep snow and we followed their trail over the pass. I’ll always remember that.

Find out more about Arlene over on her website and her quarterly newsletter.

Her books

Breaking Trail: A Climbing Life and Annapurna: A Woman’s Place

are well worth a read too.