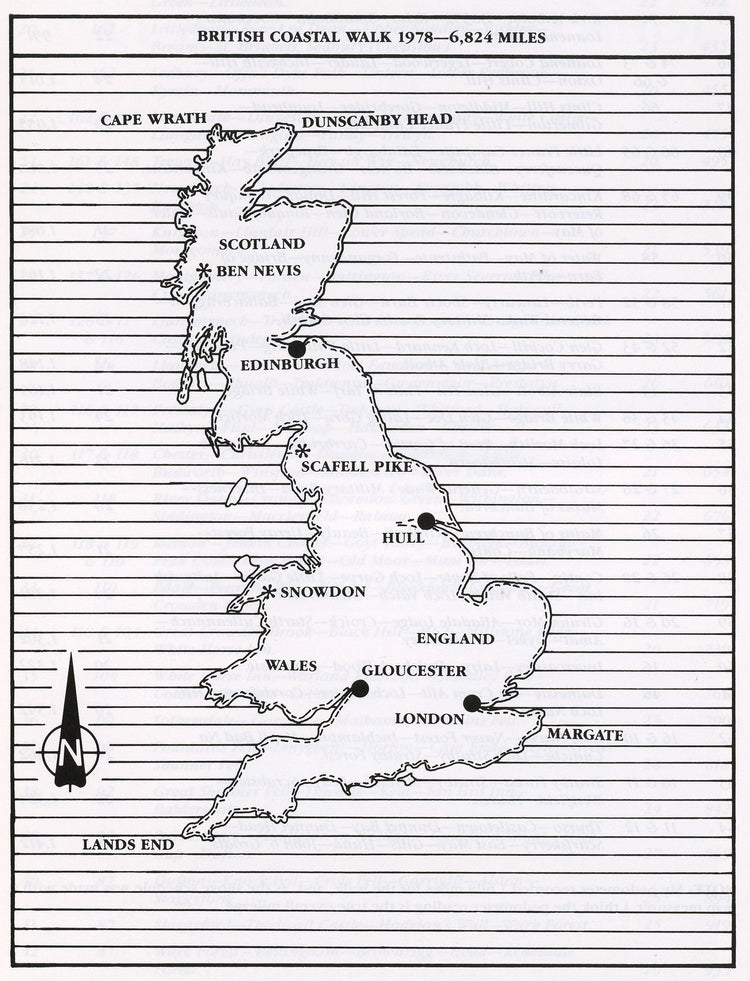

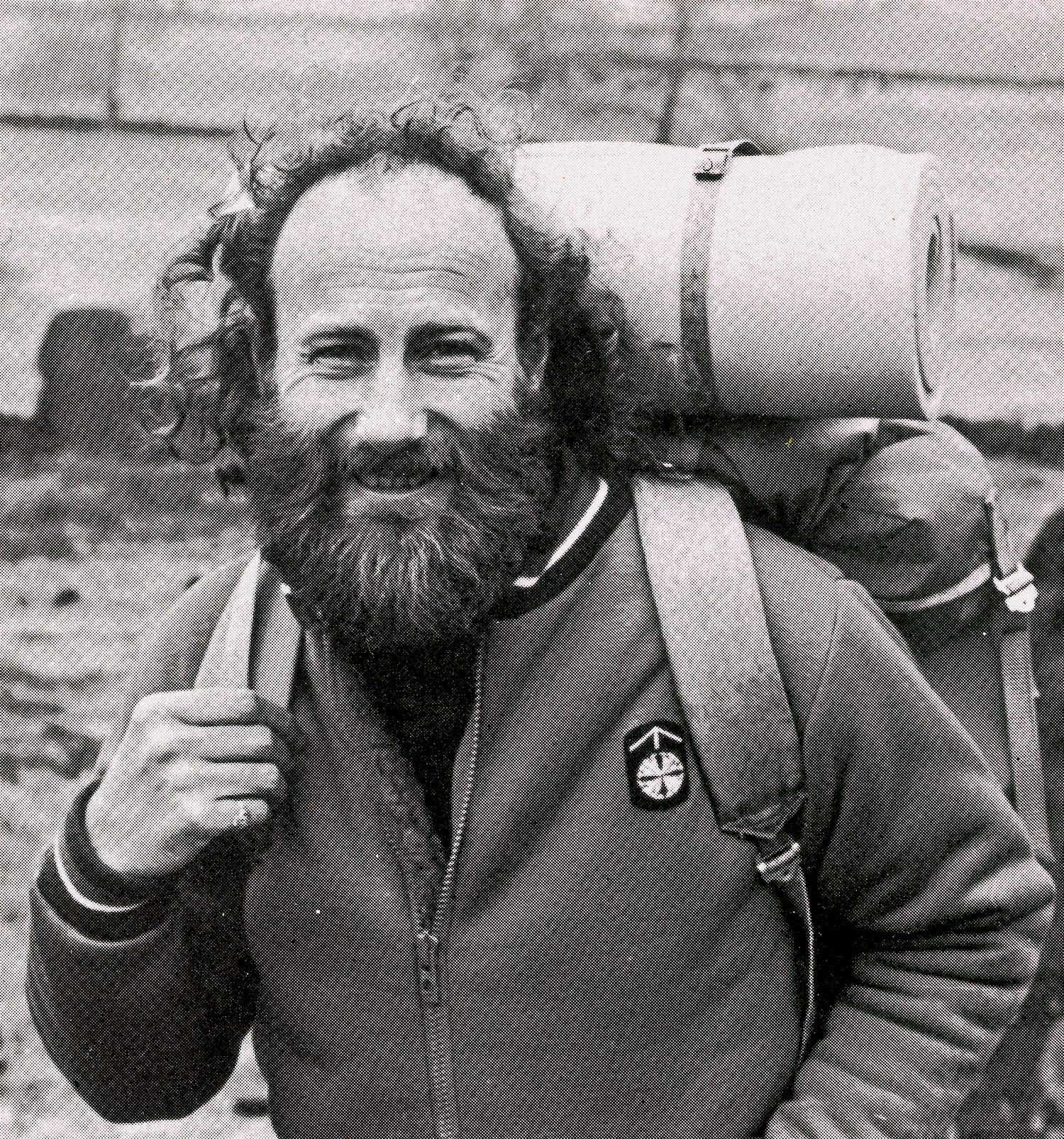

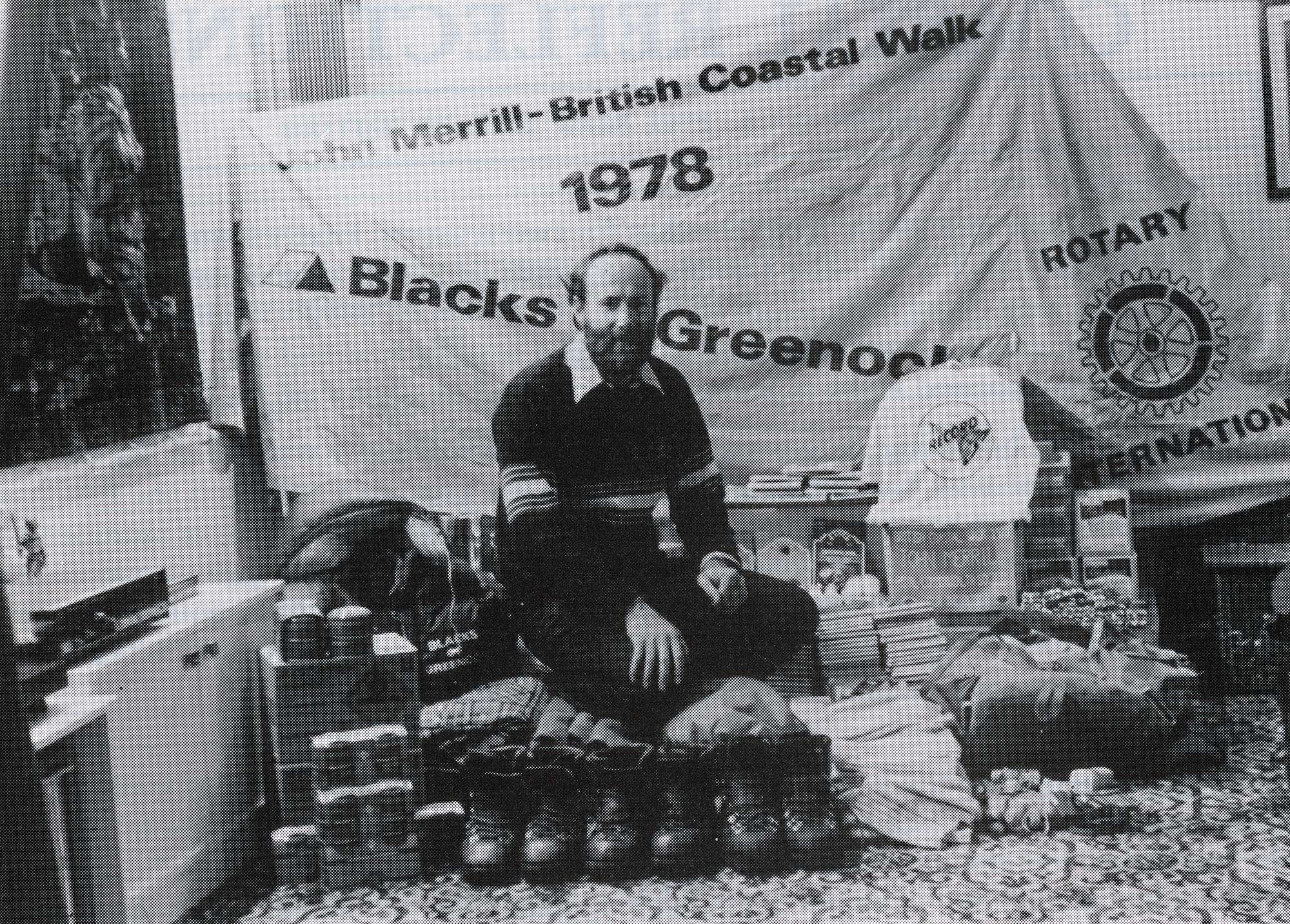

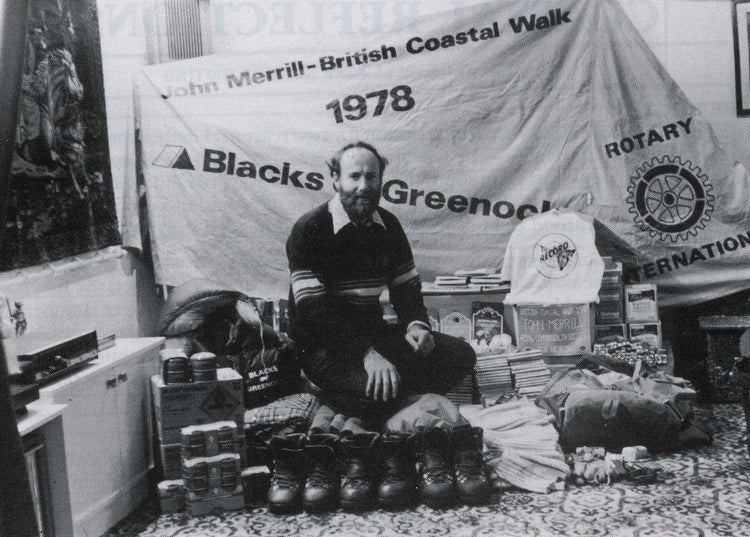

Write about John Merrill and it’s easy to get swamped in numbers. This is a man who has walked over 228,000 miles, worn out 153 pairs of boots, and written more than 520 guidebooks. As far as long distance walking goes—he’s quite literally out on his own; the first human to walk the full length of the British coast along with countless other big-mile achievements that won’t all fit in this intro.

But don’t get the wrong idea. Whilst these numbers might make him sound like some sort of militant machine, a trail-walking T1000 whose only goal is to stroll, he’s actually a freewheelin’ wanderer with a penchant for chocolate bars and local history. What’s more, despite his endless achievements (including his honorary masters degree), he’s still a true outdoor outsider—ignoring trends and cushty brand deals to go his own way.

Here’s an interview with him about walking, water, boots, books, past-lives, not seeing another human for 14 days, and the beauty of not knowing what’s around the corner…

Sam: I suppose the first thing I want to know is why you walk? Some people ride their bikes for miles and miles, some people sail around the world—what is it about walking that got you hooked?

John: Well, I suppose it’s the most natural thing—and you see the world at its own pace. If you’re cycling, you miss half of it, and you don’t get that connection to the earth.

Sam: Was it something you were always into?

John: It started when I was six—I was at a school in Sheffield, and one afternoon they took the whole class out to the Peak District. I ran up and down the rocks, and that sense of freedom and exploration made a deep impact. I knew from that moment on that the countryside was where I should spend my life.

Sam: When did you go from being a kid running around in the countryside to being a ‘serious walker’? What was the first long distance walk you did?

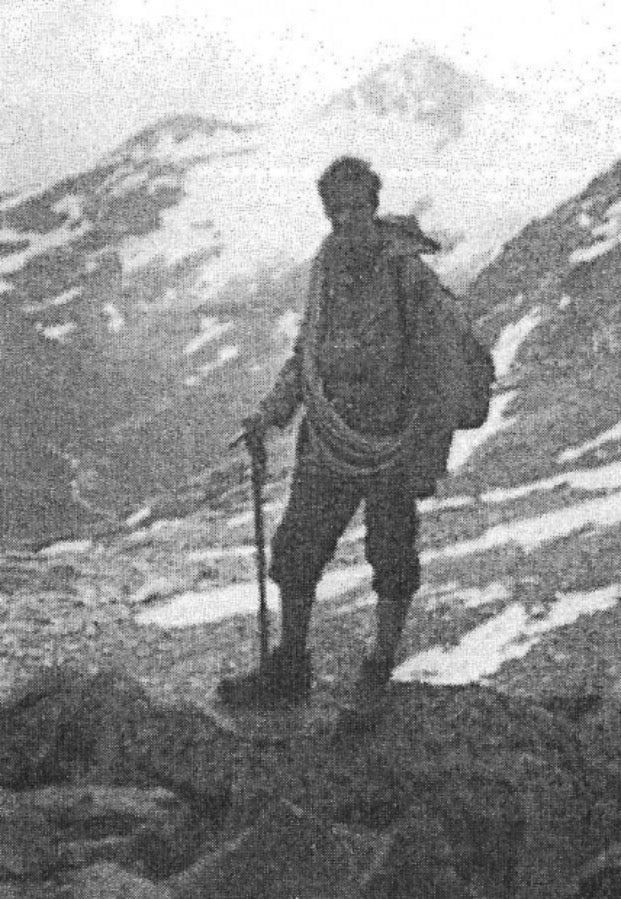

John: I’d say that was in Norway. I was one of twelve chosen to go on an expedition to Norway for three weeks—hiking across glaciers and climbing mountains. The guide who took the course said, “Come back next year and I’ll train you to be a guide over here.” So I went back the following year and had another week learning how to cross glaciers, and from there I had decided I’d like to explore the Jotiunhiemen—so for three weeks I crossed 28 glaciers and climbed all the highest peaks. It was an amazing experience for a 16 year old.

Sam: That’s quite a contrast with what most people are doing at 16—just milling around aimlessly.

John: Prior to that I’d done a lot of climbing in the Peak District—soloing around—and one day the headmaster caught me climbing up the school building. They were quakers—so you didn’t get caned by them—you just had to stand to attention whilst you got a lecture. He leant across and said, “I think you had better be properly trained.” So they got me onto a month-long outwards bound course in the Lake District, and there I learned how to map read and how to go alone on an expedition—and it went on from there.

Sam: Were you always good then?

John: I was naturally athletic anyway—at a previous school at the age of ten I went in for every race—and I either won them or came second. I was very shy, so when it came to prizegiving I hid in the toilets. The headmaster found me an hour and a half later to present me with the school cup. I was always bottom of the class at everything.

Sam: These huge walks you do strike me as more than just being a physical challenge. How do you manage walking for so long?

John: How long do you mean? I say that if you walk the Pennine Way, you haven’t begun…

Sam: Haha—fair enough—what do you class as a ‘long walk?’

John: At least 1,000 miles. For the first 500 you’re settling down and getting into the rhythm of being out in the countryside and walking. But after 1,000 miles you’re totally at one and you can start pushing yourself quite incredibly—especially at 1,500 miles. At that point nothing is too hard for you—you can do 40 miles, and then the next day do another 32 miles. Then after about 2,500 you start to physically decline.

Sam: Declining in what way? What starts happening at that point?

John: You know you’re not walking as you were. I did find that after 3,500 miles I was getting pains in my knees—but I shook that off and carried on. Your performance becomes quite ragged—so you can do 17 miles and feel fine afterwards, so the next day you’ll do 20 miles and it’ll be a struggle.

Sam: I can’t imagine many people get to the point of releasing this stuff. Not many are walking over 1000 miles.

John: I just set off and don’t have any preconceived ideas apart from where I want to get to at the end of the day. And then as I’m walking along, these miracles appear. I might come to a crossroads and meet a man standing there who might give me some information about the route ahead—and maybe they’ll tell me to look out for a building and tell me the history of it. And I wouldn’t have known that because I don’t do any research beforehand. If you know beforehand what you’re coming to, it doesn’t have the same impact.

Sam: That’s kind of at odds with the world today. We all want to know what the restaurant is like before we eat there, or what the beach looks like before we get there. Does that attitude ruin things a bit?

John: Yeah, it spoils it totally. I’ve never not found anywhere to stay at the end of the day—I just let it unfold. On a big walk the night before I’ll look on the map and see where I want to be at the end of the next day, and so I’ll get up in the morning and my mind is already programmed to get there—irrespective of how many miles away it is—and then it just unfolds and you get to the destination, fresh.

When I was walking through Spain a man stopped me in a street in a village—and said “Oh you can stay at the monastery at Ourense.” When I got to the square there was a rope hanging down with a bell—so I rang that and the door opened and there was this cistercian monk in white robes. He took me through this stone building where they were saying prayers—and then I came into this en suite room with carpets and everything.

Sam: The luxurious lifestyle of the modern monk?

Yeah—I joined them for prayers and then we shared a meal—and then at the end I made a donation. Three days before I’d been walking along this small road by a lake, with nobody about, and there in the middle of the road was 25 euros—so when it came to give a donation to the monastery I gave them 50 euros—25 of mine and the 25 I’d found. The monk was a bit flabbergasted, so he ran off to the abbott and he came to talk to me. He said, “How many miles have you walked?” I told him I’d done 198,000 miles overall—and the monk immediately bent down and started kissing my boots. I had to lift him up and say that I wasn’t worthy. They all came out and saw me off onto the trail—waving until I was out of sight.

Sam: You wouldn’t have had that if you just booked into a Travelodge. This sort of open attitude takes quite a bit of confidence and courage. Do you ever have any fear or uncertainty with how things are going to pan out?

John: You just go in with total faith and have no doubts. When I walked the Pacific Crest Trail I’d go 14 days without seeing a human being. I was carrying 14 days worth of food so I could camp and cook food every night, and I never came to any harm, and always arrived as planned at the next food drop. I don’t expect anything, I just let it unfold.

Sam: Doing these huge walks on your own would maybe be seen as a bit dangerous—but what’s the reality? Are most people welcoming?

John: Yeah—most of the time I don’t really reveal what I’m doing. When I walked across America, I couldn't say I was walking to San Francisco—I’d just say I walked from the previous town. Because they couldn’t get their heads around it.

But yes—basically people are welcoming. I was trekking in the Himalayas once—I was high up on this ridge and I came to this hut you could stay in—a bamboo shelter. Whilst I was there three unsavoury characters came in, so the owner of the hut sat on my bed all night to protect me. Life is cheap there—if you kill the sacred cow wandering the streets in Kathmandu you get 15 years in prison, but if you kill a human being you get one year. And all your gear—your sleeping bag, your rucksack and everything can be sold to make more than they’ll make in a year. But most people have been more than helpful.

Sam: When they make films about this stuff, it’s like they need to add some daft dramatical element in. But in reality is it all pretty relaxed?

John: Yeah—there are all these programmes about doing walks or pilgrimages—they miss all the good bits and they have to put in all these bits that don’t really happen. There’s so much out there of interest on the walk itself, without you having to fabricate anything.

Sam: What are the good bits? What do you look back on at the end of the day?

John: Maybe you’ll go to the church and see some old gravestones or some murals on the wall—and maybe there’ll be a story behind them. Maybe you’ll see a gravestone that says, “Wild Boy”—and you’ll research that, or you’ll see the grave of a highwayman. If you’re open to things, it’ll all unfold in front of you.

Sam: How does it feel to be on your own for 14 days? Nowadays with phones and the internet it’s hard to be fully ‘on your own’—so what’s it like to be away from all that for two weeks?

John: It is strange. After 14 days, I came to the end of a ridge, looked down into the valley and saw a house. It took me four hours to get down there, and for half an hour I just chatted frantically to the post man—and then after that I didn’t see another person for eight days, when I had to stop because my rucksack had collapsed. It’s strange—you’re looking at everything as you go along—the flowers and the birds—and you’re reading the landscape. You’re quite busy as you’re walking along—but not concentrating on the actual movement of walking.

Sam: What about when things go wrong? I imagine it’s hard to stay positive all the time.

John: You just dismiss it really. If you come to a river that you can’t cross, you might have to walk to find a reasonable crossing place, but you just take it in your stride–accept the situation and resolve it. You’ve got to find another way around it rather than dwell on it, because that will just pull you down psychologically.

Sam: I suppose if you’ve not had any pre-planned ideas of how the day was going to be, you can’t be disappointed.

John: No—it’s not like when you’re walking in this country and you might plan to meet someone at a pub at midday—there’s none of that, you’re totally free to find your own way and see everything.

Sam: How do you then adjust back into life at home after something like a 4,000 mile walk across the USA?

John: It takes about three months. Like how on the walk it takes the best part of three months to reach your peak performance as you adjust from the ‘modern life’ to being a solitary person walking through the countryside, at the end of the walk I usually camp outside for a couple of weeks. I can’t get in bed because it's too soft—and when I do get in I can only get a couple of hours’ sleep. It takes about a month to build up to getting eight hours of sleep.

I still wear the boots and the shorts I’ve been wearing for at least three weeks, because the thought of going into long trousers just doesn’t feel right. It takes the better part of three months to really adjust to modern life after having walked 4,000 miles.

Sam: And then is there a point where you get the itch again? How long does that take?

John: Initially, going out for a days’ walk after a big walk means nothing, so I won’t go out a lot. But then after three or four months you’re already thinking about the next one, and you think, “I better go out and break the boots in and get fit again.”

Sam: What do you take with you on one of these trips? What do you eat?

John: I just have a very basic single-man tent, maybe a couple of t-shirts, two pairs of shorts and half a dozen pairs of socks. I don’t really bother with over-trousers or waterproof jackets. I don’t drink water during the day—I’ll go twelve hours without drinking. That sort of horrifies a lot of people, but it’s the way I was made—you can’t judge it just like that.

In a previous life I was a bedouin in the desert with 300 goats. And the bedouin will have a drink at breakfast, and then they set off to the next oasis and they don’t drink until they get there. They have nothing during the day. The fact is that the more you drink, the more you want to drink. And then the more your drink, the more you sweat.

Sam: And what about food? Didn’t you used to eat loads of chocolate bars?

John: I still eat a few. When I set off on the coast walk, at first I’d have two or three a day—by a month I was eating four, and then after three months I was eating eight a day. It’s just energy.

Sam: Do you have any preference for chocolate bars? Which was your favourite?

John: Any! After the coast walk I did approach Cadbury’s with an idea to do an advert for Cadbury’s Fruit and Nut, but they never took it up.

Sam: You would have been the ultimate ambassador. What about your boots? I suppose you’ll know better than anyone what makes good walking footwear—which are the best?

John: The traditional heavyweight boots would last 2,500 miles, and they’d just feel like slippers. But today’s lightweight modern boots—if I get 800 miles out of them I’ve done well. The heels just wear right through. The brands don’t really like me because I wear out their boots too quickly.

Sam: I was going to talk about that. Some people who do these kinds of long distance feats get sponsored by brands or write glowing reviews for magazines—but you don’t seem swept away in that stuff.

John: Oh no—I tell the truth. I upset Berghaus when Gore-Tex came out because I was testing the jackets and I told them they didn’t work. They didn’t understand that each human is made differently—I generate a lot of heat, so the Gore-Tex just couldn’t handle it. That’s why I don’t wear it—I just wear a cotton wind jacket. I’d rather get wet but stay comfortable than have a cagoule on and be soaked inside.

Sam: When did you start writing about your walks? Was it just a natural thing to want to share your experiences?

John: I remember I walked around the Isle of Arran, and after that I looked on a map and saw the Isle of Mull—which was about 240 miles right around—so I decided I should walk around that, take some photographs and maybe write some articles about it. So I wrote a few articles, and they were all accepted—and then I realised that there was no real walking guide to the Peak District, so I wrote this guide, Walking in Derbyshire, and I sent it to the Dalesman, who were the first publisher I thought of, and they accepted it. It sold 9,500 copies, and when they told me they weren’t going to reprint again I said that they should split it into two books. The short walks book sold 90,000 copies and the long walks book sold 60,000 copies.

Sam: And you just kept going since then? You’ve published hundreds now.

John: Yeah—I gave my father six months’ notice so I could write the book and do lectures and so on, and at the same time I was planning to walk 1000 miles linking all the islands of the Inner and Outer Hebrides together, so I wrote a book on that. I actually went back to my school on an open day after five years of writing books. I was always bottom of the class at everything and I failed everything, so when I saw the English teacher I said nothing, but I just pushed across 20 books of mine which had been published. He went very quiet.

Sam: You seem very modest and humble about your life and your achievements—but these walks are completely out of the realm of how most people live. Where does your drive for this stuff come from? And what’s kept you going?

John: Well, most people are one hit wonders—but then there are people like Tiger Woods who just keep going and winning more and more competitions. I’m hoping to walk from Canterbury to Rome, which is 1,400 miles. And then I’m planning to do the 88 temple pilgrimage in Japan, which is 1,000 miles. And then there are two big walks in Australia. And I’ve worked out a 2,000 mile walk in New Zealand. It continues—it never stops. I just have this urge for adventure—to discover more. That’s part of the driving force.

Sam: How has getting older affected your walks?

John: I was 80 last year, and the only difference is it just takes a bit longer. I still walk the same distances, but instead of doing about three miles an hour on average, it’s now about two and a half miles. I still have no aches and pains at the end of the day. I’ve worn out 153 pairs of boots. I’ve got a shed in the garden with them all in—with little labels on to say what they’ve done. I’ve got this crazy idea that when I do finally die and get buried, instead of throwing roses on the coffin, you just throw the old boots on.

Sam: It’d have to be a big hole for that many boots. Looking back on all these walks—is there a specific moment that really stands out.

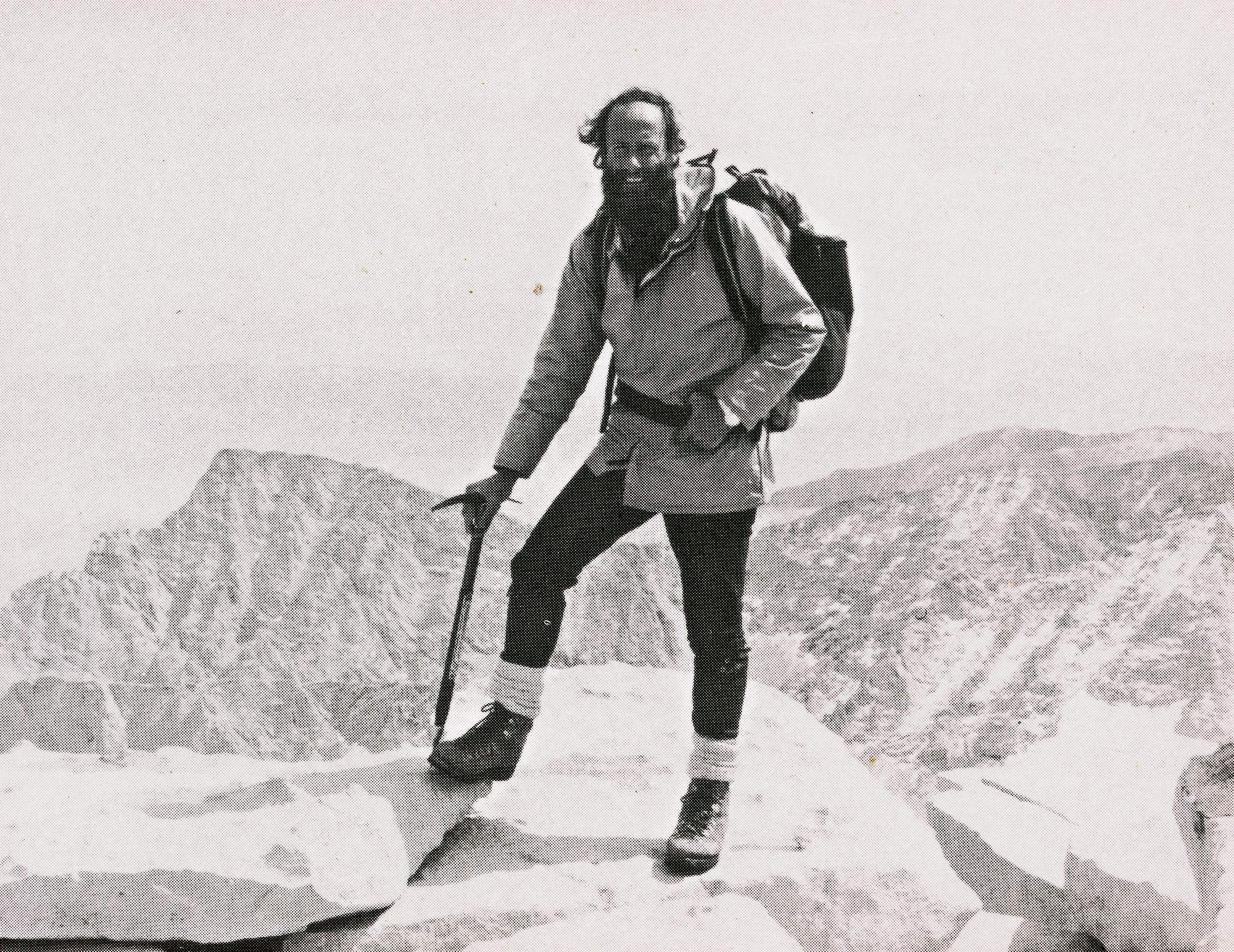

John: There are some things I’ll never forget. When I was walking around the coast of Britain, I decided I’d climb the three highest mountains as they’re all within a day’s walk of the coast. I set off up Snowdon in my shorts and a t-shirt—and after walking 2,000 miles you’re as fit as a flea, so I was on the top in no time. When I got to the summit three figures came out of the mist—three climbers with ice-axes and ropes and everything—they all shook me by the hand and said, “Fancy meeting you here.” They’d been following my walk. I jokingly said to them that I’d be on Scafell Pike in about a month, and I’d see them there. And this is a totally true story—we had no correspondence at all—but when I climbed Scafell Pike and got to the summit, who should I meet but the same three climbers?

Sam: Haha—amazing. Wrapping this up a bit, have you got any wise words for those wanting to walk?

John: Yeah—don’t listen to anyone—just do what you believe is right. For every mile you walk you extend your life by 21 mins.