It wouldn’t be a wild overstatement to say that the Whole Earth Catalog might just be one of the most influential publications to come out of the counterculture movement.

First published in 1968, this printed database of items and ideas—featuring information on pretty much everything you could ever need, to help you do pretty much anything you could ever want—was a vital resource of the pre-internet age, famously described by Steve Jobs as ‘Google in paperback form’.

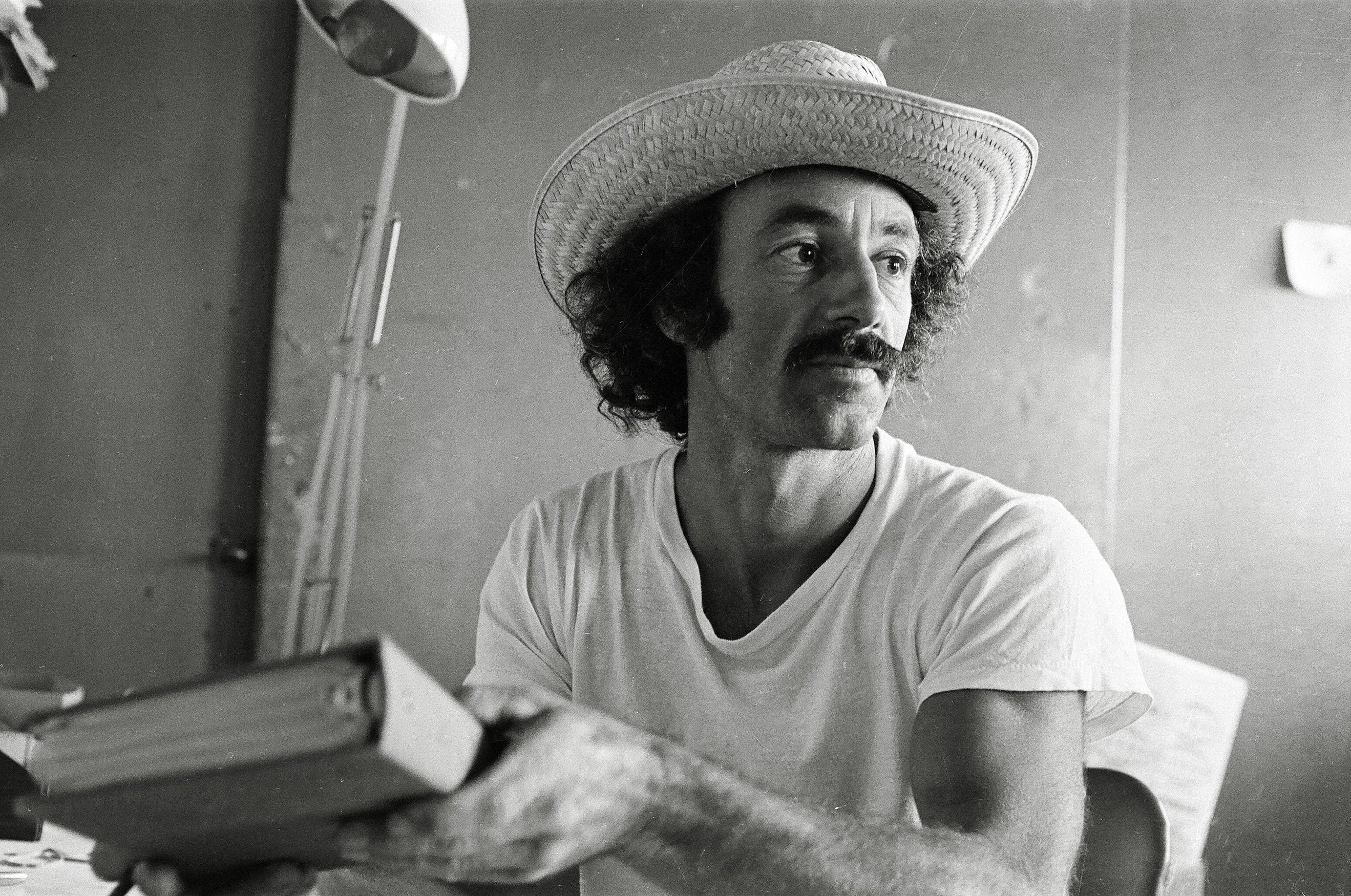

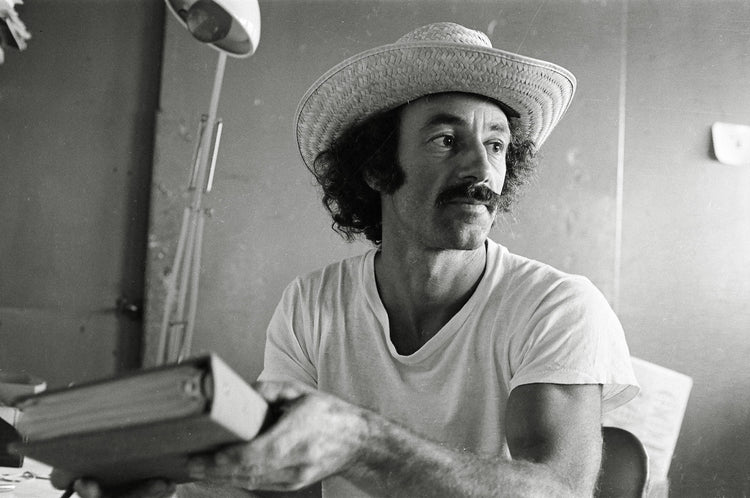

Lloyd Kahn was one of the key figures behind it. As ‘shelter editor’, he was responsible for the parts of the catalogue devoted to buildings—writing about the tools and methods needed to put a roof over your head.

But the Whole Earth is far from the whole story for Kahn. Taking inspiration from Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome concept, in the early 70s he created Domebook—a vital tome for those who wanted a dome as a home—before turning his back on the hemisphere to publish perhaps his most famous book… Shelter.

Released in 1973, this unique book was an oversized, info-packed guide to DIY house-making that has sold over a quarter of a million copies.

Even that isn’t the full story. More than just a writer and publisher, he’s also a skateboarder, bike rider, surfer, carpenter, forager, gardener and about 500 other things—and whilst he might be 88 years old, he still lives with the same curiosity for life and the world that made his work so inspirational in the first place.

Our old mucker Sam Waller caught him whilst he was watering the plants in his greenhouse to talk about life in the 1960s, working on the Whole Earth Catalog and how he’d make a house today…

Sam: Before Shelter, before Whole Earth and before you worked in construction, you worked in insurance. What made you drop out of that and get into carpentry and counter-culture?

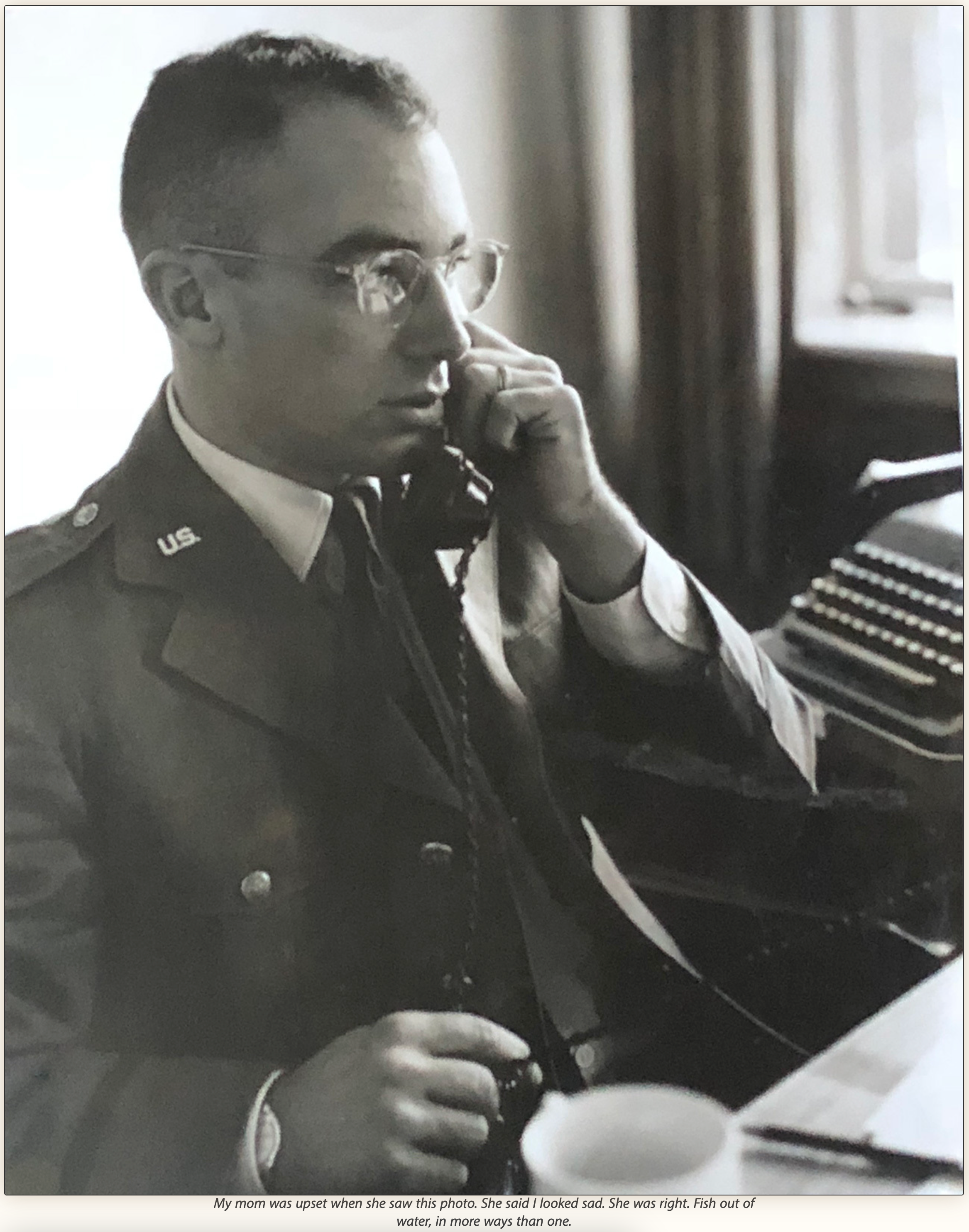

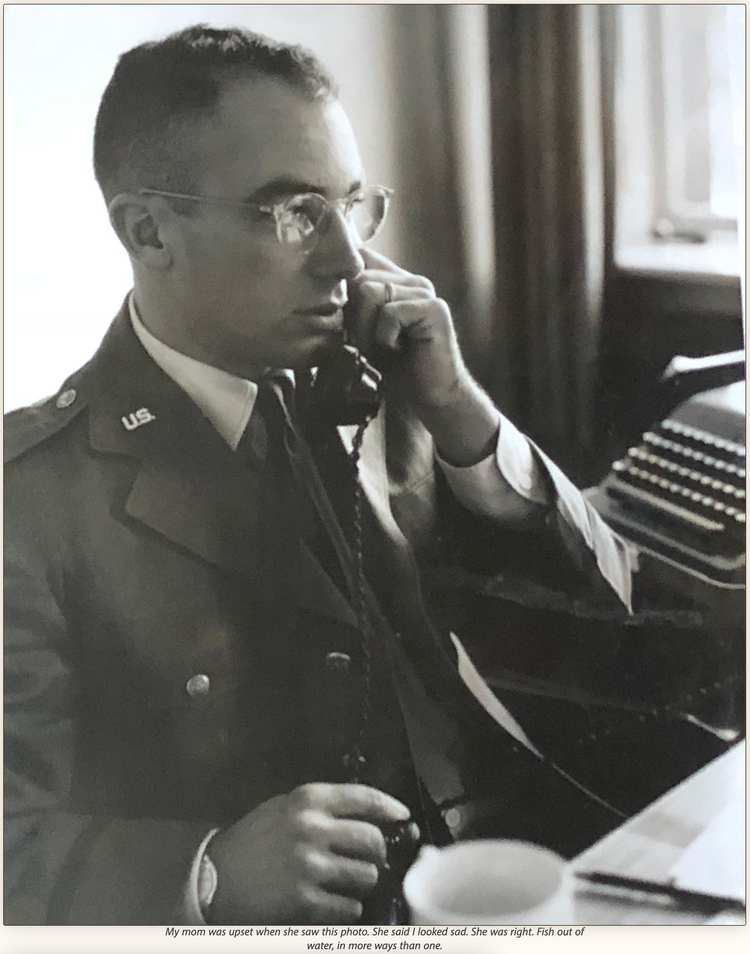

Lloyd: I ran a newspaper in the Air Force in Germany in 1958 to 1960, and when I got out of the Air Force I came back to San Francisco and got into the insurance business with my dad and my brother and my uncle. My brother and I started doing really well, but around 1963 I started smoking pot—and at the same time I started looking into other things. I would go to zen meditation before going to work—and I got interested in all the things that were starting to become popular with the counterculture.

In 1965 I took a month’s leave of absence and hitchhiked across the country—I just thought things over, I stayed in New York, I went out to Cape Cod to stay with my cousin, and then I got a drive-away car back. I came back a month later and I remember looking at the freeway going into San Francisco one morning and thinking, “I’m quitting.”

So I quit my job and went to work as a builder. I hated wearing suits—especially ties—but if I stayed at it like my brother did I would have been a multi-millionaire. But I chose another life—I started hanging out with the younger generation—people ten years younger—the baby boomers.

Sam: I suppose you had lived long enough to know a life before that stuff. You knew both sides of the coin.

Lloyd: I kind of saw things from a dual perspective. Nobody else in my generation really did what I did and dropped out of high school or college. I dropped out of that world—that straight world—and started a new life.

Sam: This whole era of counter-culture is talked about so much—but what was the reality of it? Was it as much of a noticeable shift or movement as it seems like in films or in books?

Lloyd: Being from an older generation I think it gave me another perspective on what was going on. That’s always been helpful to me—to have grown up in a time with no television. When I was born in 1935, there were five million people in California. Now there are 40 million people here. So the population has increased eightfold. That’s huge.

When I dropped out and went to work as a carpenter, you could get by on very little money. The 50s and 60s were kind of the peak of prosperity in California. America came out of the war with production facilities that were built to make aircraft and tanks, and they turned all that into making appliances. So it was really easy to get by. In 1966 I got a job building a large house out of bridge timbers on a 400 acre ranch in Big Sur—this mountainous area on the coast below San Francisco. We moved down there and lived in a chicken coop.

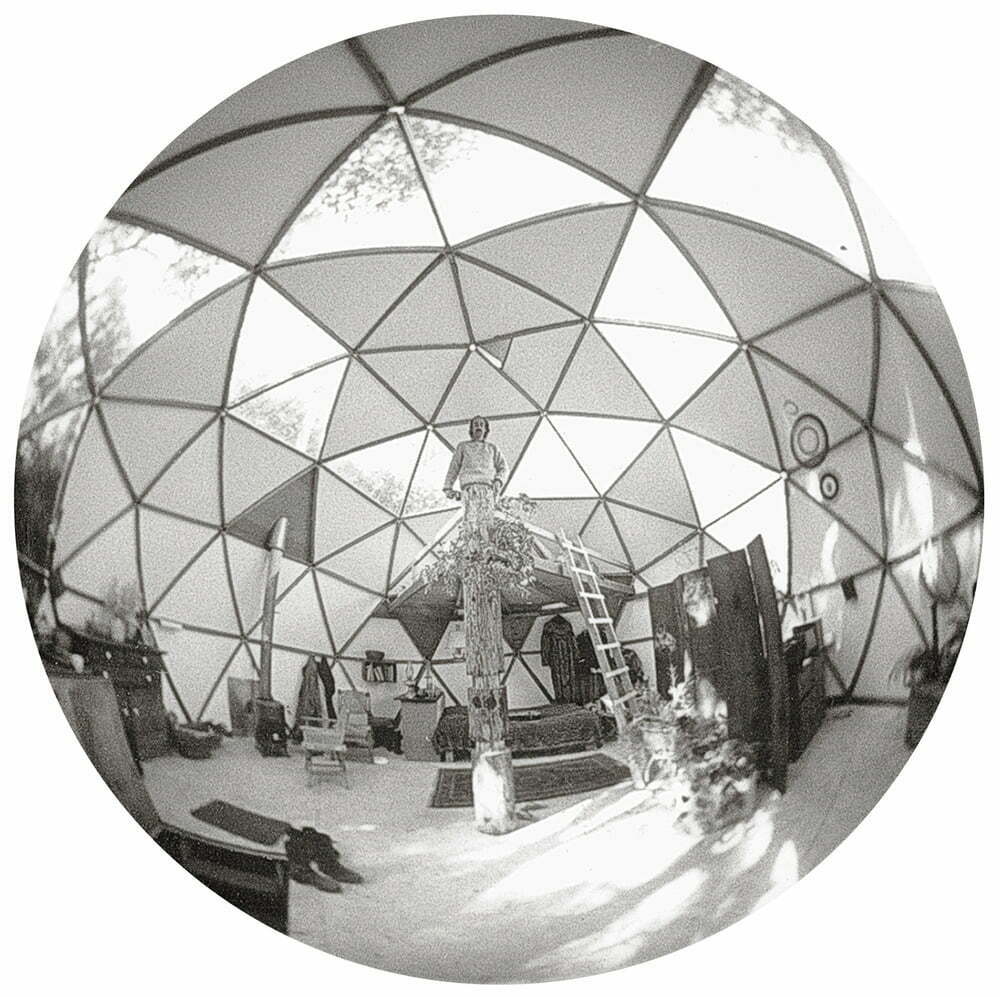

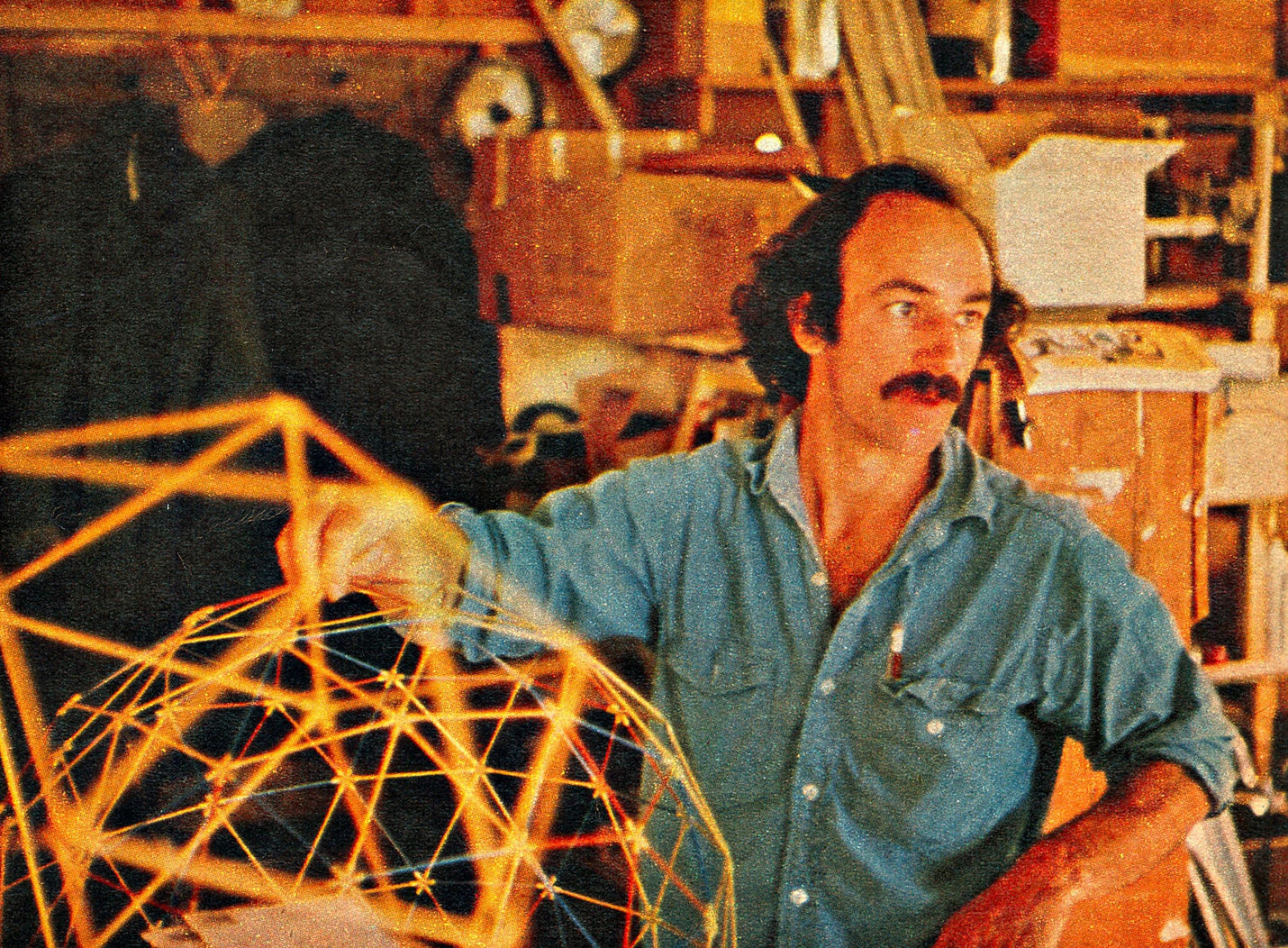

I was living there building this large house and all of this other stuff was going on. We’d go up to San Francisco on the weekend to go to the Fillmore Auditorium and the Avalon. Around that time, probably as a result of building this very large house out of bridge timbers, I wanted to do something different. We’d heard Buckminster Fuller talk and we were very inspired by what he was saying about lightweight ethereal structures, so I started building domes. I quit the job building the big house and built my own house down there. Once I’d got that finished I built a couple of domes.

People started writing to me for the mathematics, and I realised I was writing the same letter over and over again, so I thought that I should print something up instead. And at the same time I had learned stuff about organic gardening and building your own house and growing your own food and communicating with dolphins and books like Dune and Stranger in a Strange Land and Eastern religions, so I put all that together in a little pamphlet.

Sam: I imagine a lot of people were building stuff back then, but what made you want to share what you knew? Most people just keep info for themselves.

Lloyd: I’m a freelance journalist—I’m a communicator. In high school I was very much influenced by a class in journalism. They taught us about how you need to get the who, what, where, when, why and how in the first paragraph. I’ve always wanted to tell people what I’ve run across in the world. Everybody does that with Instagram now—they go out, they take a picture of a sunset and suddenly ‘boom’—they can publish it. And I’ve always wanted to do that since I was a kid. So when all these things came around in the 60s—astrology, astronomy, zen buddhism, rock and roll, I wanted to share them.

Our system of education was totally western orientated. At Stanford the one course that everybody had to take was Western civilisation, but that didn’t take into account the Asian civilisation, or anything that went on in Europe. So there was a huge amount of stuff that we learned in the 60s. It was just a blizzard of new things that we discovered in the 60s. They weren’t really new things—like organic farming—a few people already knew about it, but what happened was all these things became known to the baby boomers with this huge population group. A lot of these things were things that the Beat Generation knew about, but they didn’t share the information. They were kind of negative.

Sam: They were too cool to share?

Lloyd: Yeah! That’s why I was so excited by what was happening. I remember at the Monterey Pop Festival thinking everything was going to change—people were going to start respecting the earth and respecting each other and we weren’t going to have war… it didn’t work out that way, but a lot of the ideas we had back then were right. Even in spite of the horrible things that go on in the world right now, there are still things we believe in from back then.

Sam: How did you start working on Whole Earth? It sounds like you were already doing something similar.

Lloyd: I met Stewart Brand—who had the same idea about everything that was happening then, but he was much further along than I was. So I joined forces with him and became the shelter editor for the Whole Earth Catalog. And that’s how I learned how to make books. Stewart had a big effect on my life, and a lot of other peoples’ lives too.

Sam: What strikes me about Whole Earth is how it’s so open. It’s got ‘products’ in, but it’s not like some selling tool. If it was made now it’d be a big branded advert. The Whole Earth Catalog is just honest—it’s just telling people about good stuff.

Lloyd: People who used this stuff were writing about it. So if you discovered a chainsaw or a kit for making moccasins, you wrote about it. It was honest. There is what I’d call an electronic version—a website called Cool Tools.

Sam: Oh yeah—I’ve seen that. That’s done by Kevin Kelly isn’t it? I’m reading a book of his right now but most of it is going over my head. He worked on the Whole Earth Catalog too didn’t he?

Lloyd: That’s him. He didn’t work on the Catalog, but he worked on the magazine. There was the Next Whole Earth Catalog and the Last Whole Earth Catalog—and it got out of control. There was the magazine called the CoEvolution Quarterly, which was a spin-off, and then that morphed into the Whole Earth Review. That went on for years and years. Kevin kind of took over from Stewart. He wrote very short, direct reviews of things, just like Stewart did.

Sam: Whilst you were working on Whole Earth you published your books on domes too didn’t you?

Lloyd: I borrowed Stewart’s equipment to do Domebook 1 and Domebook 2. Typesetting was done on this 9,000 dollar typewriter called an IBM Composer. That's how printing was done in between linotype and the Macintosh.

By the time Domebook 2, had sold 150,000 copies, I realised that domes didn’t work. So I had to admit that I was wrong—and when you admit you’re wrong in front of that many people, from then on in your life you’re never afraid to say that you’re wrong. It had a very big audience, and we could be still selling it now, but I took it out of print in 1972.

Sam: What was wrong with the domes? Why didn’t they work?

Lloyd: There are a lot of reasons domes don’t work. They just don’t make as much sense as rectilinear construction. They don’t take into account the landscape. I actually wrote something called Refried Domes. Every once in the while there’ll be a wave of enthusiasm for domes, but I’ve gotten to the point where I don’t even discuss it with people anymore—I’ll just say, “Hey, just go read this thing. I put it all in writing.”

Sam: So you went the other way entirely and made Shelter? I imagine that was sort of the opposite of Bob Dylan going electric—you went from mathematical sci-fi houses to more traditional methods of building.

Lloyd: I thought, “Well, I’ve got this big audience, I should be telling them about all the other ways there are to build.” So I travelled across America and Canada and went over to England. I learnt a lot in England about building. I had a friend who rented a house in a little town on the Thames called Mapledurham. You know where that is?

Sam: Not really—I don’t really know the South of England.

Lloyd: It was the perfect village, with the almshouse and the baker’s house and the miller’s house. So I hung out there and learned a lot about building—taking pictures and travelling where I could—and eventually making the book, Shelter. I followed the building that went from England to the East Coast of the United States, and then across to California.

There are a lot of people in buildings who don't realise how much work it is to build a home. It's not like a painting or a sculpture where if you don’t like it, you can throw it away. So they think, “I want to build a straw bale house.” but that’s really a lot of work. So I came to the conclusion that I wanted to build a house that was aesthetically pleasing and felt good to be in, but I didn’t want to spend my whole life doing it. If you’re going to build a seven sided tower or a freeform house, it’s going to take you five times as long and be three times as expensive as sticking with rectangles. That’s one of the things I’ve learned—and I try to tell people that. If you don’t pay attention to the history of things you’re going to repeat the same mistakes over and over again.

Sam: That was something I wanted to ask about. Although the 60s were seen as very progressive—a lot of the ideas were sort of fresh takes on old concepts.

Lloyd: We said in Shelter that we were looking at the way things were done in the past, without just going back and trying to do everything the old way. We were trying to find a balance between the wisdom of the past, and the requirements and conditions of the present day.

Like I said, it was so cheap to live back then that we could try things out—but it’s not that easy nowadays. Things are so much tighter now, and so much more expensive. But still, if you can’t get ten acres in the country and build a house out of trees that you can cut down, you can still just do what you can. Maybe you’re just going to fix up your apartment—you might not be able to grow your own food, but maybe you can grow some parsley on the fire escape. You just do what you can for yourself—and it’s more and more important now that everybody is sitting in front of a screen all day to do something physical.

Sam: When you were working on this stuff back then, did you have any idea how influential they would be? Even now they’re constantly referenced or talked about. Did you set out to make something that would change people’s lives?

Lloyd: Shelter really did change people’s lives—it was amazing. I didn’t think about that back then, but we knew we were onto something. Shelter took three months to put together, and for the first printing we did 50,000 copies. We didn’t know anything about publishing, and you’d never do that nowadays—that’s a huge risk. It was about 50,000 dollars, which is a lot of money 50 years ago, but it just sold like crazy. And then I did a book called Shelter 2.

Around that time I got together with my wife Lesley—we built a homestead here and tried to make a living farming, but we just couldn’t do it. I got back into publishing in 1980 when I published a book about stretching. It sold over three millions copies and it’s in 23 languages—it’s in Latvian! That’s been half of my income for the last 40 years, and after that I did all these books on fitness.

Sam: Is stretching the key to staying young? You’re pretty healthy and nimble for your age.

Lloyd: For my age I’m pretty healthy, but it’s a pretty low bar. People don’t take care of themselves.

Sam: How have things changed since you published Shelter? Are more people doing things for themselves now? If you look one way, it feels like everyone’s living in a campervan, but then if you look another way, people are paying a fortune for dull, badly made houses.

Lloyd: I don’t think people are doing it like they were back 40 years ago. I don’t know anyone right now that lives within 100 miles around me building their own house, whereas in the 70s there were 35 of us in this small town building our own homes. It’s gotten much more expensive. But then for the younger people—people your age—they’re seeing what we did back then and saying, “I like this, this is pretty good.”

I don’t know if you’re generation X or a millennial, but it’s encouraging to see these people of your generation who are into this sort of thing, but the world isn’t the same as it was 50 years ago.

Sam: Why do you think people are getting into this stuff again—foraging for mushrooms and growing their own food?

Lloyd: I don’t know—it’s just the passage of time, I guess. You’re going to have to do things differently, but some of the principals will be the same. If I was your age now, living in the States, maybe I wouldn’t go and look for ten acres in the country, I’d look around in a small town, or maybe a city that had more of a working class background like Oakland—and I’d find a neighbourhood where they’d just chased out the crack dealers. I’d find a house there, and try and fix it up. That way you’ve already got your wiring and plumbing.

A friend of mine a few years ago bought a house in a small town in Oregon and fixed it up. That’s the way I’d do it now. And then you do as much gardening as you can, realising there’s no way you can be self sufficient. I have a pretty good size garden and I eat a lot out of it, as well as doing a lot of foraging for mushrooms and clams and mussels and crabs and whatever fish I can catch. I pick up roadkill deer—I almost got one the other night—I bring them home and butcher them and put them in the freezer. So you do as much as that stuff as you can, without getting tied down with doing something unrealistic. You’ve got to make a living… unless you’ve got a trust fund. You just do what you can.

Sam: Is it more about the network? So you might be the guy growing the vegetables, but I might have some chickens? That way you can work together rather than just be an island.

Lloyd: Sure, yeah. It’s going to be different for everybody. A lot of people are living in vans. The last book we did was called Rolling Homes—it was about vans and pick-up trucks—people whose homes are on wheels. But at this point I’ve done my books on building, and now I’m going to write about what I see in the world. I live in a small town, but whenever I travel I get so excited. I get excited out of my mind when I go to New York. I take pictures of it and write it up, so I’ll start putting that out.

Sam: Where does this curiosity come from? Even at my age people can shut off and not care anymore, whereas you’re 88 and still buzzing off this new stuff—constantly looking for something fresh. What has kept that going?

Lloyd: Well, the world is a fascinating place. It’s nothing to do with me—it’s just that all I have to do is go into San Francisco, and wow—here’s a new noodle shop that’s just opened up. You know what I did recently? I went to see the Taylor Swift movie—and it was fantastic. She’s a fantastic woman. There’s just a lot of interesting things going on out there, all you have to do is walk out of your door.

If I’m in New York sometimes I don’t know what I’m going to do, so I’ll just walk out of the hotel and I’ll find things. Here’s a shop window that’s wonderfully curated… here’s a restaurant… here’s some guys playing jazz in the park… I just find everything to be of interest. I went to visit one of my best friends from high school yesterday, and he doesn’t have long to live but he’s at this huge house—and I didn’t like the house very much—but the garden was really nice. He had a pool and a waterfall and oak trees, and I was asking him about mushrooms—he had porcini mushrooms under his tree.

I’m just interested in things, and I find that when I get depressed, what really gets me out of it is to take a bike ride or to hike or to paddle my paddleboard or jump into cold water—to do something physical. What I like to do when I work out is to have an adventure. I don’t just want to run on the pavement—I want to go out in the woods and see things. On an electric bike I can cover three times as much ground as I can on a mechanical bike—so I can see things. The trees. The forest. The deer. The ocean. I find the beach is endlessly fascinating to me—and I’m lucky that I can walk to the beach from my house.

I think a lot of people are neglecting their bodies and thinking that everything is mental—but everything is connected, and your mind is in your body.

Sam: This stuff is so obvious that we forget it. Riding a bike or swimming in a lake is seen as a weird thing to do, whilst getting food delivered straight to your door and watching Netflix all day is seen as totally natural. We’ve got it flipped.

Lloyd: I watch a lot less TV now. When my wife was here we watched a lot of TV and she knitted. We’d watch TV at night, but now that she’s gone I just listen to music or work out with kettlebells or Indian clubs at night. Or I’ll read. I put up a post on my Instagram the other day of my fireplace, and I said about how if I turned on the TV it’d suck all the energy out of the room. The thing with television or going to the movies is that you have to pay attention, so you can’t really do anything. It’s not really a good thing to watch too much TV.

Sam: It’s like when you have people around your house and you put the TV on, everyone just starts watching it and stops talking. It kills it.

Lloyd: Yeah. It looks like I’ve got a delivery happening here, so I’m going to have to stop talking pretty soon.

Sam: Okay, I’ll try and wrap this up. Looking back on all this stuff—are there certain parts of it you’re particularly proud of? You’ve been involved with some pretty important things.

Lloyd: Well, building this place here—I’m proud of that. And I’m proud of the books. I’m not so proud of some things that I’ve done—but mistakes are part of life. Winston Churchill said something like, “If you’re not making mistakes, you’re not trying anything new.” One of the things you have to learn is that you can fuck up, and you can start over again. That’s just part of an ongoing life and a quest for adventure.

Thanks to Lloyd Kahn for the words and to Sam Waller for the questions.

Lloyd keeps a great blog which you can read here:

Lloyds Blog

Follow Lloyd on Instagram:

The whole of "the Whole Earth Catalogue" is now online here:

https://wholeearth.info/