Spend a bit of time with Nick Sanders and it’s easy to feel very sluggish, and very lazy. Since the early 1980s the cyclist, motorbike rider, author and narrowboat connoisseur has been revolutionising round-the-world adventure, adding a serious dose of speed to an often free-wheeling endeavor. Just check the numbers…

In 1981 at the age of 23 he set off from his home in Gamesley on the outskirts of Greater Manchester to ride his bicycle around the globe in just 138 days.

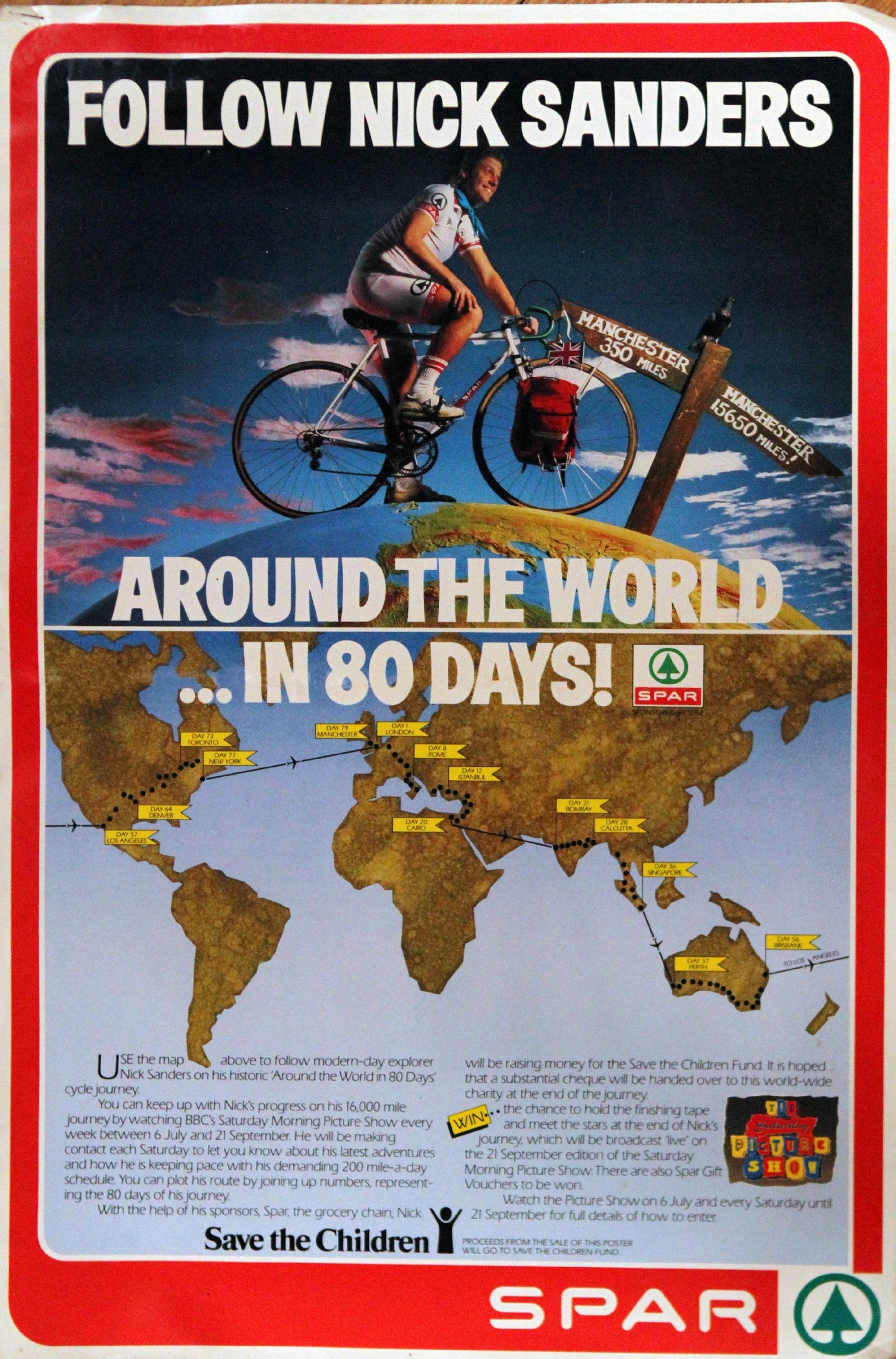

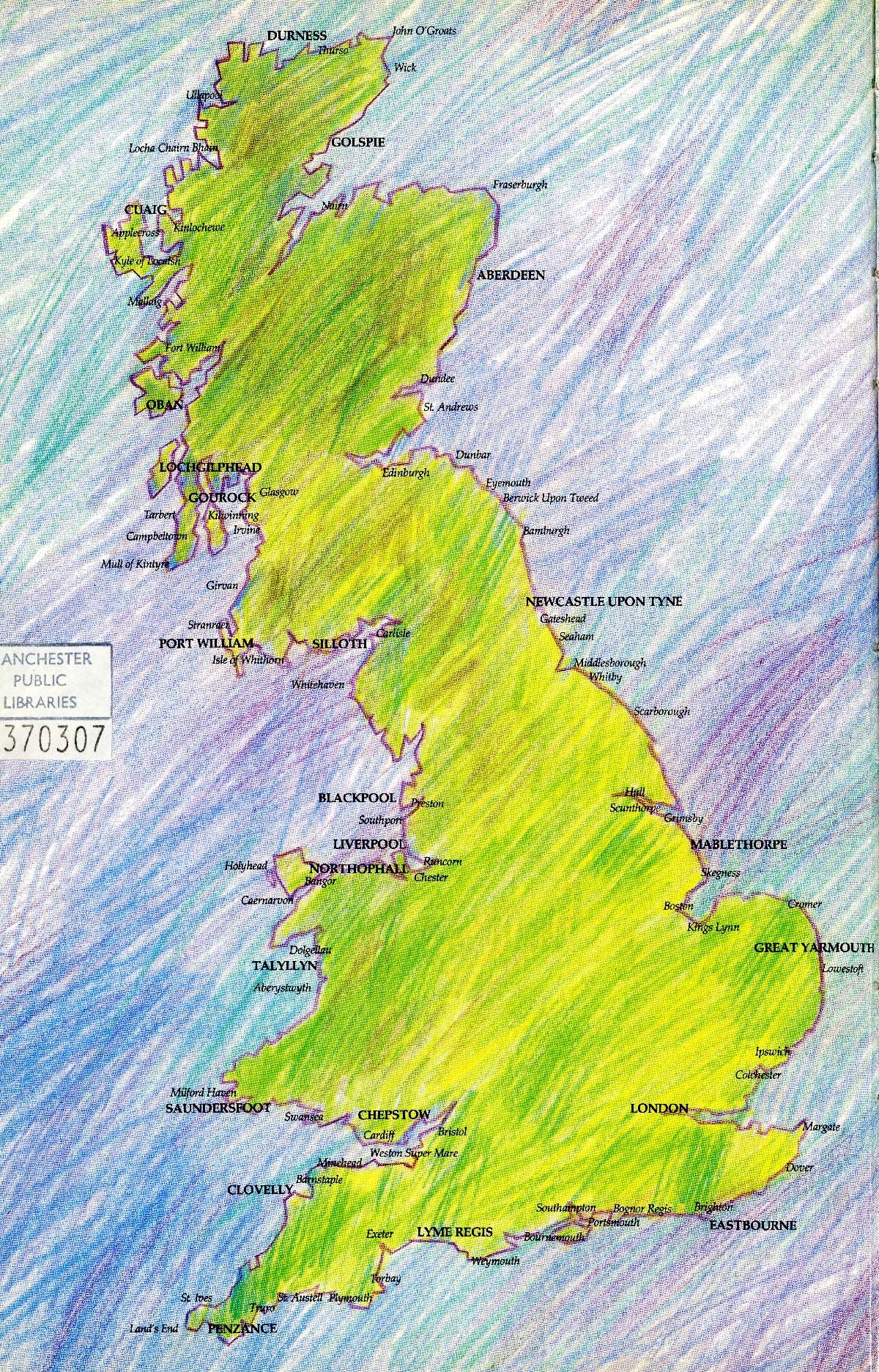

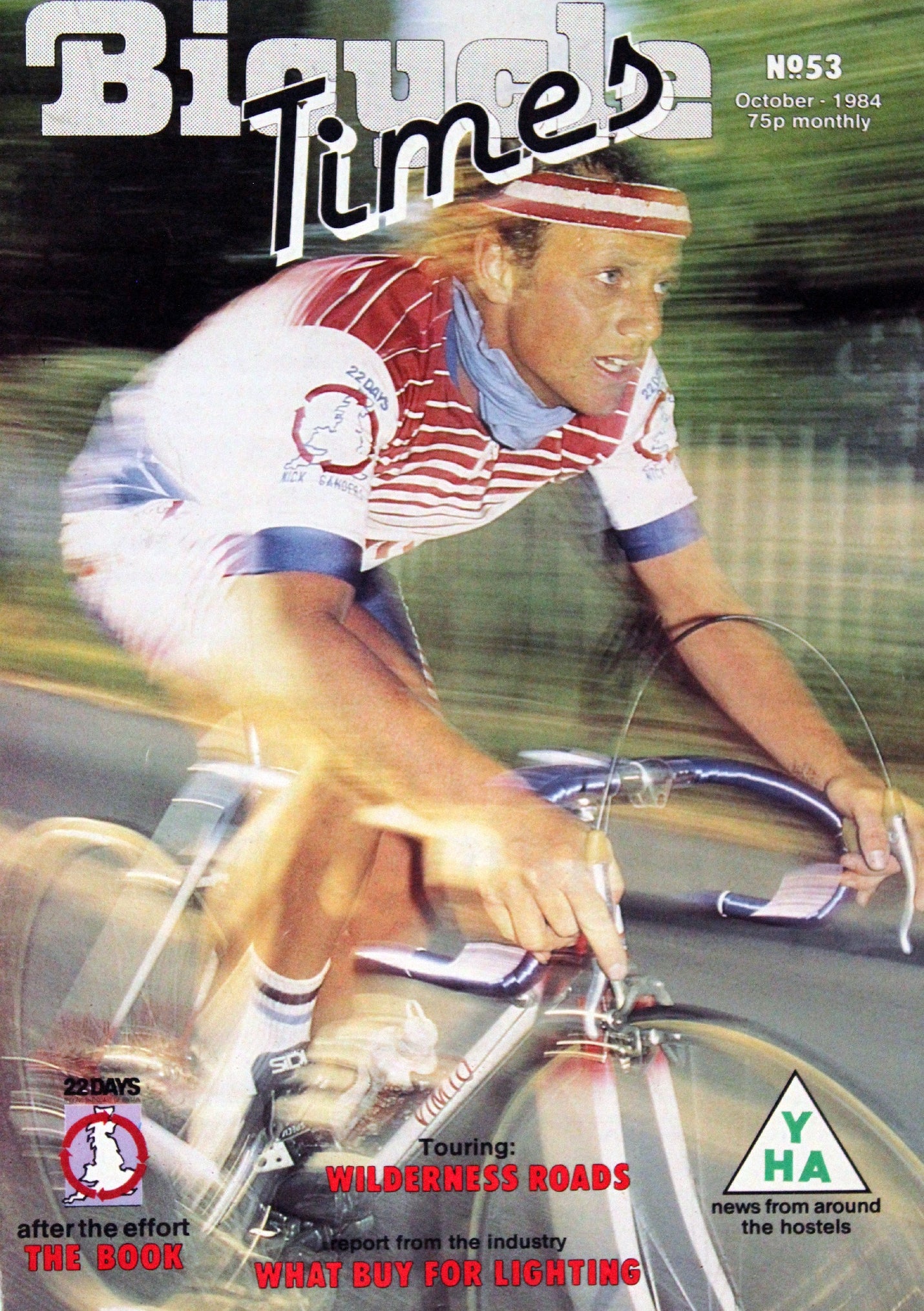

In 1984 he rode around the coast of Britain in a mere 22 days (setting a record that over forty years later still hasn’t been beaten) while a year later he went even further, outpacing Phileas Fogg to ride around the world in 79 days.

In the early 90s he traded pedals for petrol to become the fastest man to circumnavigate the globe, lapping the earth in 31 days—a time he whittled down even further in 2005 when he did it in just 19 days.

And that’s before we get onto the hot air balloon adventures, the time he took two narrowboats to the Black Sea or how just two years ago he became the first human to ride an e-bike around the world.

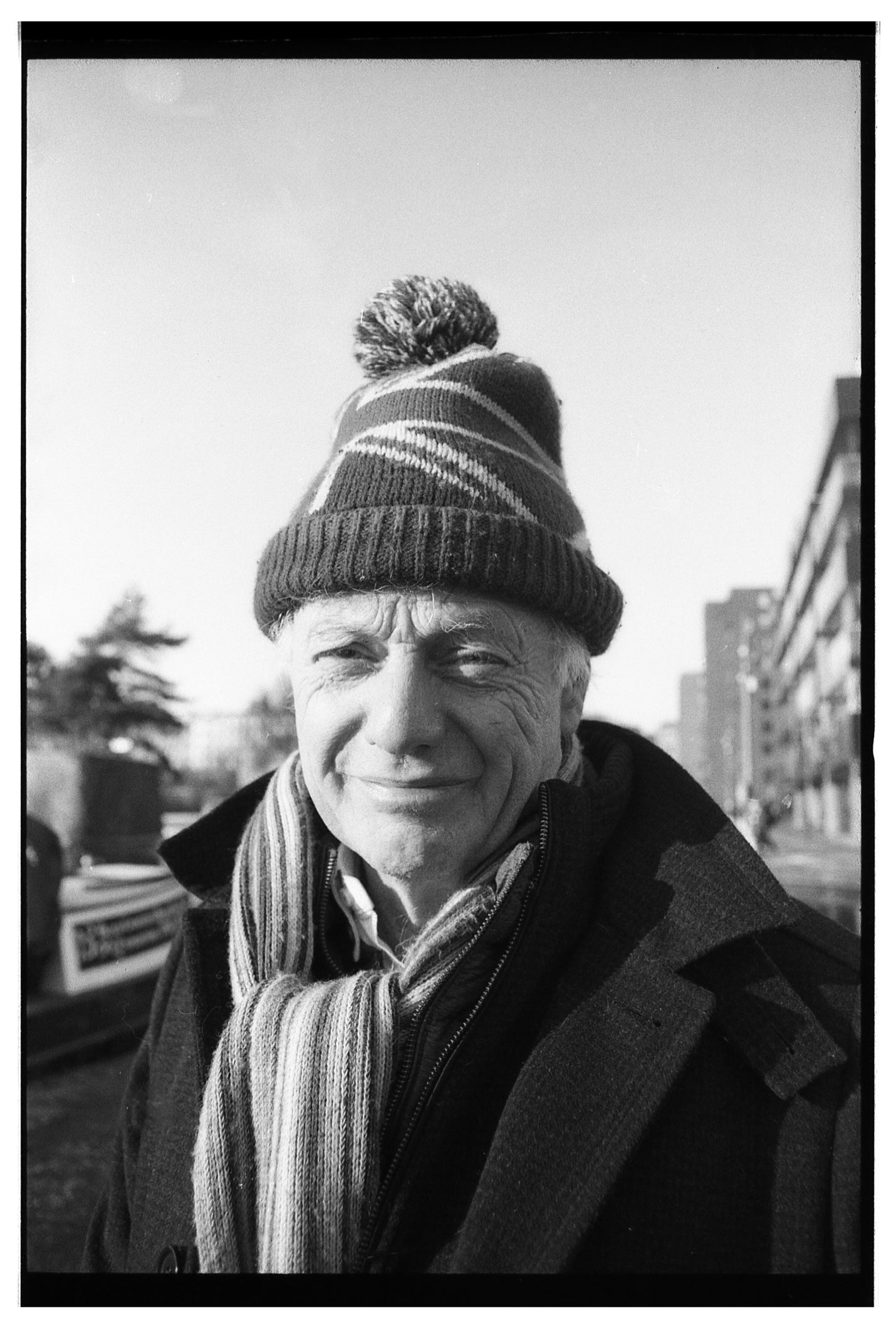

Meeting up with him on his barge one icy morning in Manchester, it’s clear there’s a lot to talk about—and while we barely scratch the surface of his endless adventures, hopefully this conversation gives at least a slight window into his world…

Sam: We’re sitting in Ancoats where you and your wife’s narrowboats are now moored. You grew up around here, didn’t you?

Nick: I was born right by the Etihad Stadium in a place called Bradford. There was Bradford Colliery, and my dad had a newsagents, so he used to sell Woodbines to the miners and bangers to the kids. It’s only a mile from here, so now I’m here it’s like I’ve come back to where I was born… I’ve come home.

Sam: Growing up in a very working class area, what was it that got you into this adventure thing? Can you trace it back to anything in particular?

Nick: There’s always something, and you’ve got to drill down to find out what it was—there’s always a reason for something that pushes you to do something at such an extreme level. I think it probably came from the dysfunction at home—Mum had a drinking problem. So I didn’t come from that posh, middle-class explorer upbringing—we didn’t go anywhere, we just went to Blackpool once a year.

We got kicked out of Ancoats and we were shifted out with 4,000 other people to a council estate in the Peak District called Gamesly. It was an overflow estate for Manchester people—and that was us. But I decided I wanted to see more, and escape family life.

Sam: So your way of escaping was by cycling?

Nick: When I was three or four, I cycled across Manchester—I escaped from home and the bin men brought me back. And that’s one of those wonderful apocryphal stories. One of the only gifts I’ve had was a huge amount of energy. When I was young, I wanted to be a racing cyclist—I eventually turned professional in France when I was 18. I worked with a team in Northern France, and I rode all the major classics—and I was pretty good at a certain level, but not enough to make any money. And I realised that very early on.

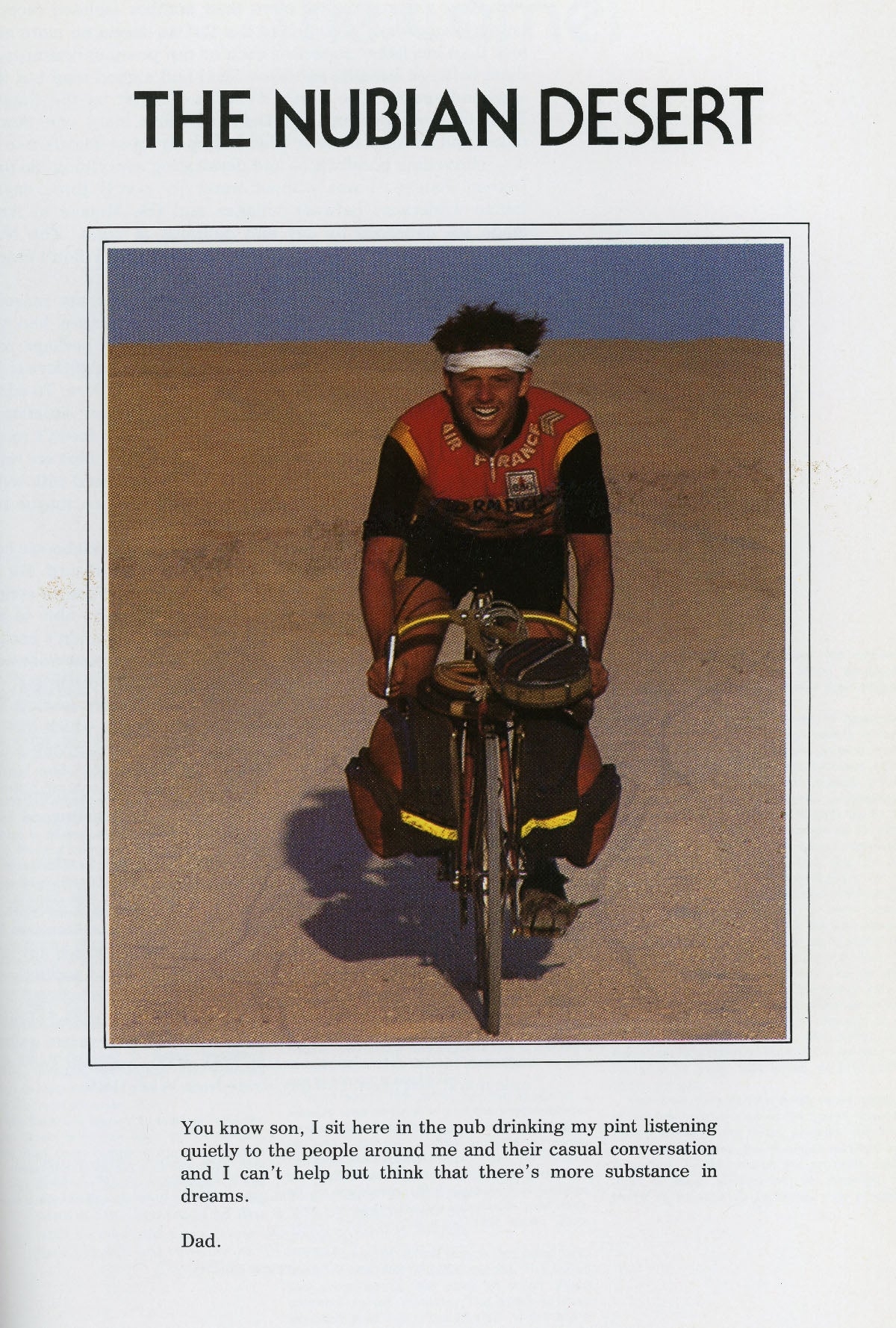

So I thought, “I’m a good cyclist, and I like travelling, so why not combine the two?” I had an epiphany—a very quick reckoning that I wanted to cycle around the world, and in 1981, I did. I had about £700 which I’d earned, and my dad gave me £100, and I cycled around the world. And it became the fastest bicycle journey around the world. Back then I was very fit, so it seemed obvious to do something for the Guiness Book of Records.

Sam: Was that in your mind before you set off? Were you aiming to do it fast, or did you set off at first just to see the world?

Nick: I was pootling around, but doing 100 miles a day without realising. And then after a while I realised that if I carried on like that, I’d get a record—and that seemed quite interesting. You have a choice in life, and my choice then was either hanging around with the beautiful people in Waikiki beach, or riding across America in 13 days to get a record. I didn’t plan it, I drifted into it—and eventually I realised that I was quite good at it. You can’t really put a finger on what it is you’re good at, but I noticed that when I travelled, I travelled very well. I’m invisible, I record it, I get data, I like working with people, I don’t get ill, I’m robust, I don’t feel anxious…

Sam: Some people would think it was just a case of having the speed and hammering the miles, but there are so many other factors into getting a record like that. Was that just instinctual?

Nick: Yeah—I learned intuition when I was a very young child. I knew what was happening around me with my family—it was very difficult, and I don’t want to play too much on that, but you either sink or swim in a situation like that, and that’s happened at a number of junctures throughout my life. If you’re an aware person, you’ll walk into a number of situations you have to deal with, because you’re always pushing the boundaries. You’ll always come up to the level of your own incompetence—it’s only a matter of time, and then you have to deal with it.

Sam: What was the reality of riding around the world in 1981?

Nick: Adventures come in cycles. I’m not the first person to bicycle around the world—it’s happened many times in the last 100 years, and people even did it on penny farthings, which is extraordinary. But what I did was I contemporised it—or at least the best I could in 1981 when no one had cameras or computers or telephones or GPS or Booking.com.

You get a letter which has waited for you in Kathmandu for about three months, and it’s covered in dust, and it’s from your dad, and when you read it, it says, “Dear Son, nothing has really happened at home, in fact it’s been pretty boring.” It really was the most boring letter I’d ever had, but I read it 100 times, and I could smell my dad on the paper. And that was the communication we had back then—it was a lot more meaningful than emails, which aren’t even read these days. We’ve lost the ability to be able to communicate meaningfully.

Sam: You said about modernising the bike tour. What did that mean back then?

Nick: Well, there were very few of us doing it at the time. There were maybe two or three people like me who were also doing this thing in the world. You may know of Nick and Dick Crane? Well, while they were cycling to the top of Kilimanjaro, I was cycling across the Sahara Desert. And while they were going to the geographical centre of the earth in central Asia, I was cycling 4,165 miles to the source of the White Nile for the first time ever. I then had to cycle back because we didn’t have a car and my dad didn’t know where I was.

I remember cycling to Kathmandu once, and I hadn’t told my father I was going—I got back after three months and he didn’t even know I’d gone away. He was still in the pub. He said, “Son, where have you been?” I told him I’d been to Kathmandu, and he just said, “Well, sit down and eat your chips, we’ll hear about it later.” That was the end of the conversation. There was no ennoblement from my parents. He’d just say, “Can’t you do anything real? Why don’t you get a job.” It took a long time to get over that.

Sam: What was the thing that changed? What validated it.

Nick: Money. And eventually I did make some money—because Spar gave me £25,000 to cycle around the world again in 79 days. The idea was ‘Around the World in 80 Days’. I’d create these concepts for the trips, because I’m from the concept album era—that early 70s thing. Like Rick Wakeman and Journey to the Centre of the Earth.

So I’d get deals and my dad would come round and see my picture in the paper and I think towards the end he understood what I was trying to do.

Sam: That concept album thing is interesting. I’d never made that link, but it makes sense. Prog is kind of big world adventure music, while something like post-punk is a lot more introspective or urban. You were going on a Tolkein-level quest.

Nick: Yeah, the post-punk music was very existential—but the music of my time was joyous and hopeful—it was about growth and exploration. There was always a narrative in those big concept albums—like with A Trick of the Tail or Wish You Were Here or The Wall.

Sam: And you applied that to bike trips. How did that first ride go?

Nick: Just ride my bike all day, then find somewhere to sleep. I camped out every night. There were no hotels. And I did that several times—I did the same thing when I first went motorcycling around the world. I did it quietly because I wanted to learn how to ride a motorbike around the world. You’ve got to learn how to do it. So I rode 38,000 miles around the world—and then in 1995 I went to Triumph and said, “Right, I will now ride your bike faster around the world than you think is possible.” I was quite cocky, but I did—I did it in 31 days, because it was the first time anyone had put speed into motorcycle circumnavigation. After 15 years of cycling, I felt like I’d done enough and I needed another project.

Sam: When you swapped to motorbikes, was it almost a thing of ‘how many more cycling concepts exist?’

Nick: I’d gone around the world in 79 days with this great concept—‘Around the World in 80 Days’—but when I got back they treated me like a clown—they made me put a top-hat on for the newspaper. I’d ridden around the world in 79 days, averaging 171 miles a day unsupported, and then I’m there in a top hat. So I’m thinking, ‘What’s the value of this journey?’ But you’ve got to get over that.

After that they said, “What else would you like to do?” So I got into hot air ballooning. I got a Spar hot air balloon and I flew all over Britain and Europe, and I subsidised my income by taking passengers. I’d supplement my big sponsored journeys by being a barnstormer—I’d take my balloon in my Land Rover, just suddenly turn up somewhere, and see if anyone wanted to fly with me, and that’s how I earned a living… until I got fed up with doing that, because after a while that’s not what I wanted to do.

Sam: Your shift to motorbikes seemed pretty seamless. You quickly broke records there too.

Nick: They hadn’t put the speed into it. Motorcycle touring is glacial—the bar for adventure for motorcycling is very low. Anyone can get a motorbike and go and ride around the world, so I had to do something different and more out there.

Sam: By this point you had a family and kids. How did you balance that with these long expeditions?

Nick: I’d keep my journeys to small packets of time—so maybe just three months away. And you can get all the stuff you need on just a three month trip, whereas the extra stuff you’d do on a six month trip is very indulgent—you don’t need to go away for six or nine months.

That was the reason for doing those fast journeys—you get back sooner. It was about going on these short, fast and sharp trips, in order to come back for being a dad. Alright, my first marriage didn’t last very long, but we did what was appropriate and it worked out fairly well. But yeah, it’s difficult. I had to earn a living.

Sam: Sometimes it feels like this ‘adventure life’ that people can lead is a side-step from normal life, but from what you’re saying, you still did the ‘normal life’ stuff too. You weren’t on an endless gap year.

Nick: You’ve got to take the kids to school. It’s easy to be very self centred and very indulgent, but I felt that dissipated when I had children—it was no longer about me, it was absolutely about them. I thought, “How do I make money now? How do I get that sponsor? How do I craft a journey so it's exactly what they need?” And I made it work.

Sam: On a more basic level, how do you adjust between these two lives—going from these high speed adventures to life at home? I know for some world travellers, it takes a long time to adjust to knocking around in their hometown again.

Nick: It’s instant. I’d ride a thousand miles a day, then I’d stop and I’d be changing nappies. That was exactly how it was. I’d completely forget about it and move on. I learned to do it because I’d done it so often. When you go on these big two year adventures, you do need some downtime to decelerate, but when you do my kind of journeys, which are sharp and fast, you’re chopping and changing all the time, so it’s part of the ability to endure what you do—being able to come home and not spend weeks readjusting.

Sam: And what happens when you don’t quite make it? There was one record you were trying to get, but you ended up being four hours short. How do you deal with something like that happening after planning an adventure for so long?

Nick: When it absolutely unravels? That’s a very interesting question. I was going for the record for being the fastest rider along the length of the longest continuous highway, which is the Pan American highway. The Guinness Record I got, in the 30 days, but that wasn’t the real record. The real record was from a particular organisation dealing with endurance motorcycling, and that record was 21 days and four hours—and that’s what I was going for.

I was on it—I was on a 19 day schedule and I was flying. I’d attempted to do this at least six or seven times before I got it right, and by the time I got within 300 kilometres of the finish, I had a little accident with the bike and I had to take out the back wheel and sort it out—and by the time I’d reconstructed the bike on my own in Patagonia in freezing conditions, I’d lost an hour. And by the time I got to the southern tip of South America it was winter closing time across the border into Argentina, and I had to wait the following morning, so I went from being four hours ahead of the record to being four hours behind it with no chance of getting it. So I got down to the bottom as the second fastest person, so I said to my darling wife Caroline, “What do I do now? Nobody likes a loser.” And she said that I had to turn around, and go all the way back up and get the double-transit record instead.

Sam: So you turned a negative into a positive.

Nick: I got my bike, and put nails on the tires because the ice had formed, and within eight hours I’d set off to go all the way back to the top again. In 46 days I did something like 32,000 miles. The only way to salvage the situation was to do something even bigger than what I’d originally attempted. And that’s never been broken… because why would anyone want to do that?

Sam: On that subject, why do you think your record for riding around the British coast on a bicycle still stands?

Nick: That was a Guiness record, and it’s still there. I think I was the right person at the right time—I was very fit from being an ex-professional racing cyclist and I picked a journey that not everybody did. I can’t remember what the record was, but I brought it down to 22 days, averaging 225 miles a day.

Guy Martin tried to break it—he did four days until he got tendonitis. We chatted away before we left—I was basically telling him what to do, but he didn’t do enough training, and he copped it. He was a young man, but he still wasn’t fit enough. He had to compete with me being a professional cyclist—just being Guy Martin off the tele isn’t enough.

Sam: Even still, you’d have thought someone would have done it by now.

Nick: Some things endure—I don’t know why. Sometimes there’s a quantum leap where all of a sudden, something happens, and it’s almost unbreakable. There are certain things that can never be done. But that’s because some people have a vision, and they see beyond the normal parameters. And that’s why I do what I do—while others just think about it. By the time they go about doing it, I’ve already done it. Like taking canal boats along to the Black Sea—it’s so long it’ll never be repeated. And that’s the way it is.

Sam: What would you do now if you were in your mid-20s? A lot of these firsts that you and the Cranes were doing in the 80s have now been done, and done fast—so what would you have to do to stand out now?

Nick: That’s a very good question. The style of adventure has changed—now it’s a lot more dramatic—it’s very much that Red Bull style of adventure. Who wants to cycle around the world in x number of months? You’re out of the public eye for a long period of time—we want short, sharp and fast projects with big reactions—and then rinse and repeat—that’s what people want.

When people have got the attention span of a couple of seconds on social media, cycling around the world is very old fashioned. It’s still there for a small coterie of enthusiasts, who really get what you’re doing, but if you’re a wing-walker or something, that’ll hit the internet, everyone will see it briefly, and then we’ll all move on. That’s where we’re at.

So it’s not really a question of what would I do, but more what is acceptable in the adventure climate which funds it. I might be able to do something that’s completely out there, but no one would like it because it would take too long.

Sam: It’s got to capture the public eye, and the sponsors. This stuff is pretty fickle. You must have dealt with that yourself a bit? What’s that line about being the news today and the chip paper of tomorrow?

Nick: It’s funny you should say that. I did this horse drawn boat canal journey thing—and we got on the front page of the Manchester Evening News. We took the picture at midday, it came out at 3pm in the afternoon, and the reason why I saw we were on the front page was that I bought my horse a bag of chips. And while she was licking this bag of chips, there was the Manchester Evening News and there was us! We were at the bottom of the bag of chips within three hours of it being published. So I know exactly what it’s like for fame to pass me by.

Sam: Haha no way. Where does the buzz come from for you with these adventures? Is it the planning, or while you’re doing it, or almost that ‘type 3 fun’ thing of looking back on it?

Nick: I like having the perfect wave—where everything works so well, it’s almost frictionless. And how can you make that happen when you’re in an environment when that’s really quite difficult to achieve? I could be killed at any given moment on one of my projects—and not just in outrageous circumstances, but in very normal circumstances, like getting hit by a car.

Sam: How do you engineer this perfect wave?

Nick: It goes into a different level—an almost psychological, spiritual level where you’re tuned into everything that’s going on around you. I’ll know what's happening around me in traffic at all times—I can hear the tires and what type of trucks are approaching and how fast they're going. I know when I need to jump off the road and get out of the way because someone’s going to drive over me—and that’s happened more than once.

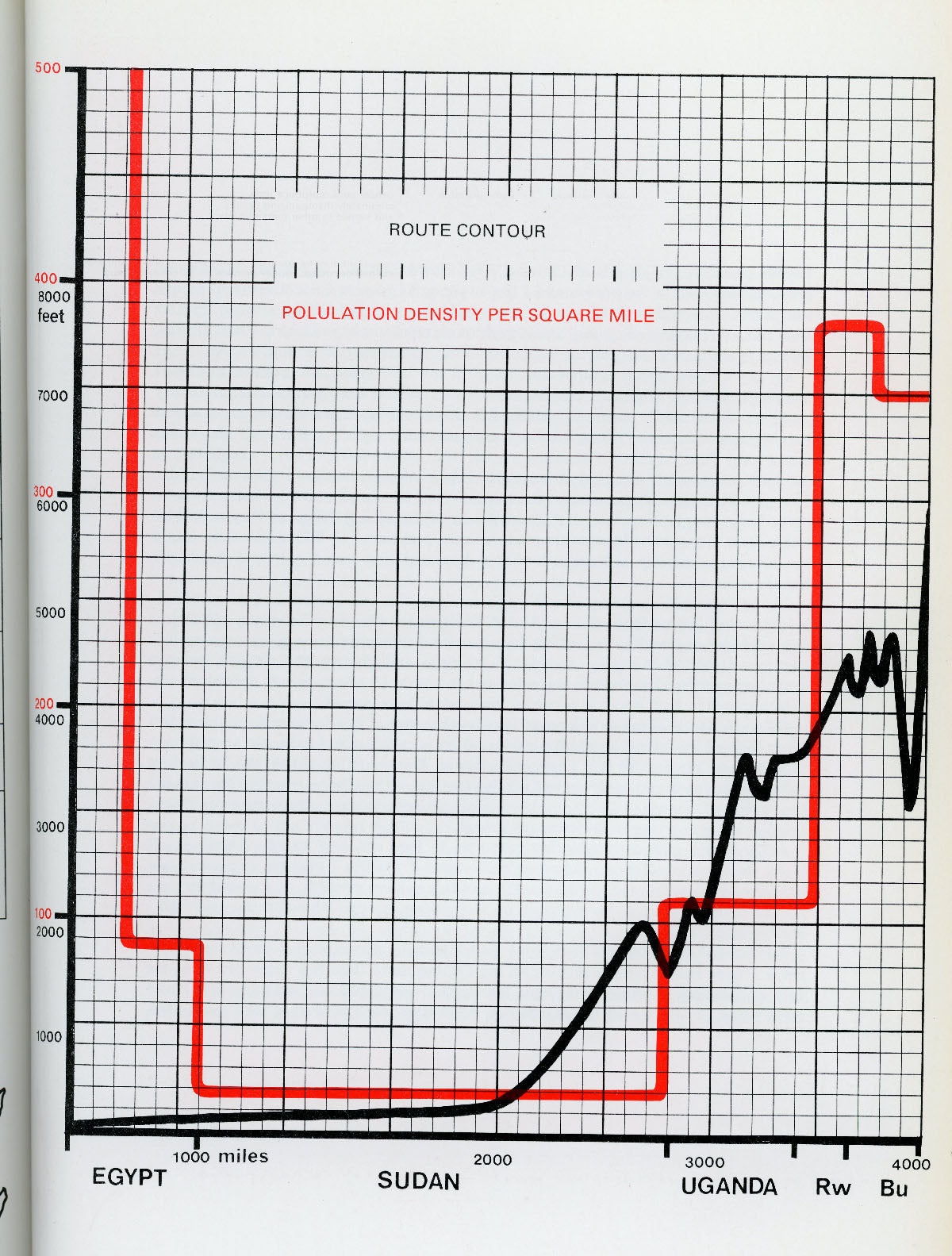

It’s something that you can’t always explain, but it’s something you develop after travelling so much. When I was cycling in Uganda, I didn’t know I couldn’t be there because it’s part of the Commonwealth, so I didn’t do my research and therefore I didn’t know they were having a civil war. So I’m going down the most dangerous road in the whole of Africa in 1983, and I survived it. I got a bus at one point, and everybody was pulled off that bus by the army and they were all killed. I was the only person left on that bus, because it wasn’t my war. There was almost this rule that they wouldn’t kill me, but it was very, very serious.

Sam: Is that where that ‘invisibility’ thing comes in?

Nick: If you’re out there, you want to be invisible. It’s of no benefit to me to appear to be a rich tourist. I need to be innocuous, just passing through. And also, you’ve got to expect that you’re passing through someone’s neighbourhood, and while there is sometimes that thing of them wanting you to feel good about where they live, you are still a foreigner on someone else’s territory. It’s almost life and death—and that’s how I used to approach these journeys.

Before I set off, I’d think, “If I were to be killed on this journey, would I still go?” And the answer was always yes. That’s how devoted you need to be to the challenge. I don’t want to die—I haven’t got a death complex, but you have to take a chance. Everything is to do with probability—whether you’re walking across the street here, or getting kidnapped by bandits somewhere else—all you can do is somehow reduce the probability to the point where it’s an acceptable risk.

Sam: It seems like when people do these kinds of expeditions, there’s often these divine moments that stick with them. Does anything like that stand out to you from your journeys?

Nick: Yes—when I was cycling to the source of the White Nile and I was in Uganda, my mother was dying. And before I left I talked with my dad and said, “She could live for six months, or two years, what do you want me to do?” And they all agreed I should carry on. But as it happened, when I was in a monastery cell on the Bomba Road, my mother came to me—it was one of those spiritual moments which hasn’t happened to me since.

After getting to the source of the White Nile and then cycling all the way back, I went to a cafe in Cairo where there was a letter waiting for me, telling me my mother had died. And I worked out when she died—and even taking into account the time differences, it was the exact time she came to see me in that monastery. And that’s an extraordinary spiritual reference point—some things you can’t explain.

Sam: At this kind of level of adventure—is it important to be open to the unknown?

Nick: Yes—you’ve basically got to open up to have a wide emotional bandwidth, in order to be able to work out if you’re safe or not. And you can only do that by completely working out what’s going on around you and when you’re with another person, working out what kind of person they are. You’ve scanned that person in a way that you can’t quite explain, but it’s a gift that’s grown in you as a consequence of doing so much travelling. We’ve all got it, but most people close down, whereas I’m constantly opening up.

Sam: I get that—it’s easy to close off but it’s not that helpful. Rounding this off, what’s your advice for someone wanting to get out there and travel for themselves?

Nick: It’s not about money. You can literally pick up a sleeping bag and a tent, and you can walk from Lands End to John O’ Groats and people will help you. You don’t need to be a skilled adventurer—if you’re just someone who wants to do something with your life, and you haven’t got any money, then yes—be inspired, go away and do it.

Kick off, live in your tent or live on the side of the road—just go ahead and do it. And then do it again. And do it again. And eventually something will happen and something will occur to you.

Check out Nick's website here.

Thanks to Sam Waller for the interview.