As outdoor activities developed in the second half of the 20th century, so too did the way they were documented. As climbing, skiing, surfing and pretty much everything else got faster—and the stakes got a fair bit higher—suddenly standing 50 feet away and pressing record didn’t quite do them justice anymore.

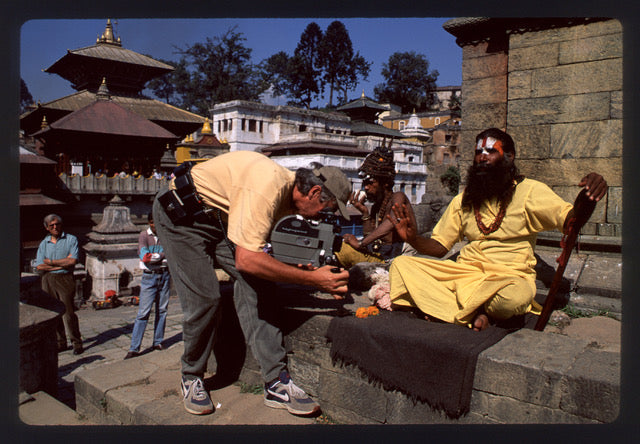

Film-maker Bill Snider was there, camera in hand, through it all—from the slow-paced days of educational documentaries of the ‘60s right up to the zany angles and ‘Migraleve-at-the-ready’ editing of the MTV Sports era. Applying a true artistic eye to outdoor action, he captured kayaking, skiing and even hot air ballooning with an up-close style which put the viewer right there in the thick of it.

The 1994 mountain bike film Tread is perhaps his magnum opus. If Wende Cragg’s photographs documented the early spark that started mountain biking, Tread showed the full-on fluorescent explosion as big brands and big money hit the trails, capturing the full spectrum of mountain biking, from back-country singletrack to packed-out race events, via ski-slope skirmishes and inner-city messenger missions.

Ditching the usual long-lens dad-cam which plagued most early MTB films, Snider was strapping 16mm cameras to bike helmets, helicopters and pretty much everything else to create an immersive visual soup that boiled down the essence of riding a bicycle in the countryside—kind of like Koyaanisqatsi on Cannondales.

Three decades on, I tracked him down to talk about cameras, bikes, helicopters and what happens when you throw ‘em all together…

Sam: Going right back, how did you get into film-making in the first place? You were making ski films and kayak films back in the late 1960s weren’t you?

Bill: In 1967 a couple of friends and I saw a movie called Goal!, which was a documentary about the ’66 World Cup that England won. It was a beautiful film and seeing it we said, “Wouldn’t it be fun to try and make something like that?” The other two guys were good white-water kayakers, so we set out to make a kayak movie. Two of us survived the relationship and finished it.

In some ways it was kind of beginner’s luck. We made that film and it was well received, so we kept doing it. We made a lot of ski stuff—in 1976 we made a cross country ski-film called Skinny Skiing. They had the International Ski Film Festival in New York, and everybody from all over the world showed up. We won our category, and then the next thing I know we’ve won Best in Festival too. And that kind of got us a foothold—doing a lot of work for ski-manufacturers. And then in the 80s we did a lot of documentary stuff—things for PBS and BBC, but in the 90s we got totally into the bike thing.

Sam: Now people can make a film and put it straight onto the internet. Or 30 years ago they’d maybe make a film and get some VHS copies made. But what did you do in the 70s? How did people see your films?

Bill: There was actually a time when a lot of public schools in the USA had library film collections. So the kayak film we did was distributed by Pyramid Films in LA, and I think their primary market was selling 16mm prints of these films to schools.

Sam: Kind of like the National Film Board of Canada?

Bill: Unfortunately in the US we never had anything quite like that. A few times we worked on some Canadian Film Board jobs, and it was like, “Wow! Look at this stuff they give you!” They just had crates of film. But no, the US never had anything like that—public television was always so underfunded. I can’t think when we got the first one of our films on television—it was probably years later. Trade show stuff was the first way things really got out there.

Sam: And was it just a case of you filming what was around you in Colorado? In the 70s it seems like there was a lot of new outdoor sports stuff bubbling up… whether it was climbing or kayaking or mountain biking.

Bill: The kayak film we did was back in the time when if you saw someone going down the road with a kayak on their car, you’d pull over and talk to them. And now around Boulder every other car has a kayak on it. But I suppose at the time it seemed fairly exotic that people were doing these things. There was another company around Colorado called Summit Films who made ski films, and they did one of the first films where somebody does a flip. And that’s so commonplace now, but I guess it did sort of start then.

I felt pretty lucky to have won that award at that film with a cross-country film, when the rest of the films were downhill skiing. Ours was more of a documentary style film—with people talking on camera, while the other films were all action, action, action. So our film, which had people talking about cross-country skiing did well at that festival, and it also did well at some other non-sports festivals. People saw it as more of a lifestyle thing.

Sam: It crosses over. Sometimes the all-action stuff is kind of meaningless to those who are uninvolved.

Bill: Oh yeah. And now the spectacle has been pushed so far. Like the Red Bull stuff—when is somebody going to get killed? I can’t remember who it was, but I remember someone saying to me, “You need to be aware that there are these guys out there who’ll jump off a cliff just to get on camera.” And there was a thing when some guy jumped off a cliff with all these cameras, thinking he was going to sell this stunt, and he died.

Sam: There’s a difference between a stunt, and a lifestyle. I feel your films show the lifestyle, rather than just mindless stunts. Was that something you were conscious of?

Bill: Yeah—and the stunts weren’t so crazy then. The sponsors who helped with Tread really saw it as a way to bring more people into the sport. “Okay, we can show it to the bike people of the world, but what we’d really like to do is to show it to more people.” So it wasn’t really about the crazy stuff. We tried to make the people real.

Sam: Let’s talk about Tread then. That was maybe the first big full-length mountain bike film. How did that come about?

Bill: I think RockShox were the ones who really launched Tread. They were here in Boulder, and I got to know the couple who owned it. We did a couple of trade show pieces, and then one day Paul and his wife Christi came over to our house for dinner and said they wanted to make a feature length film. I said, “Are you crazy? Do you know much that is going to cost?” But they thought they could do it.

RockShox were kind of a hot item at the time, which made it possible to go and raise the rest of the money. And at the same time we were doing work for MTV Sports, which was really wacky—the crazier it could be, the more they liked it.

Sam: The camera always at a mad angle?

Bill: Yeah—the camera flying around. So that section in Tread with Hans Rey in Ecuador—we shot that with MTV Sports, and the deal was they’d take the footage and cut it the way they wanted it, then we’d take it and do it our way for Tread. So I used these connections to leverage it.

Sam: That makes sense. I know some of those 80s skate videos were shot on film, but by the 90s most people had moved onto video cameras. Meanwhile, Tread is a full-on cinematic production. It does look very expensive compared to a lot of the ‘action sports films’ of the mid-90s.

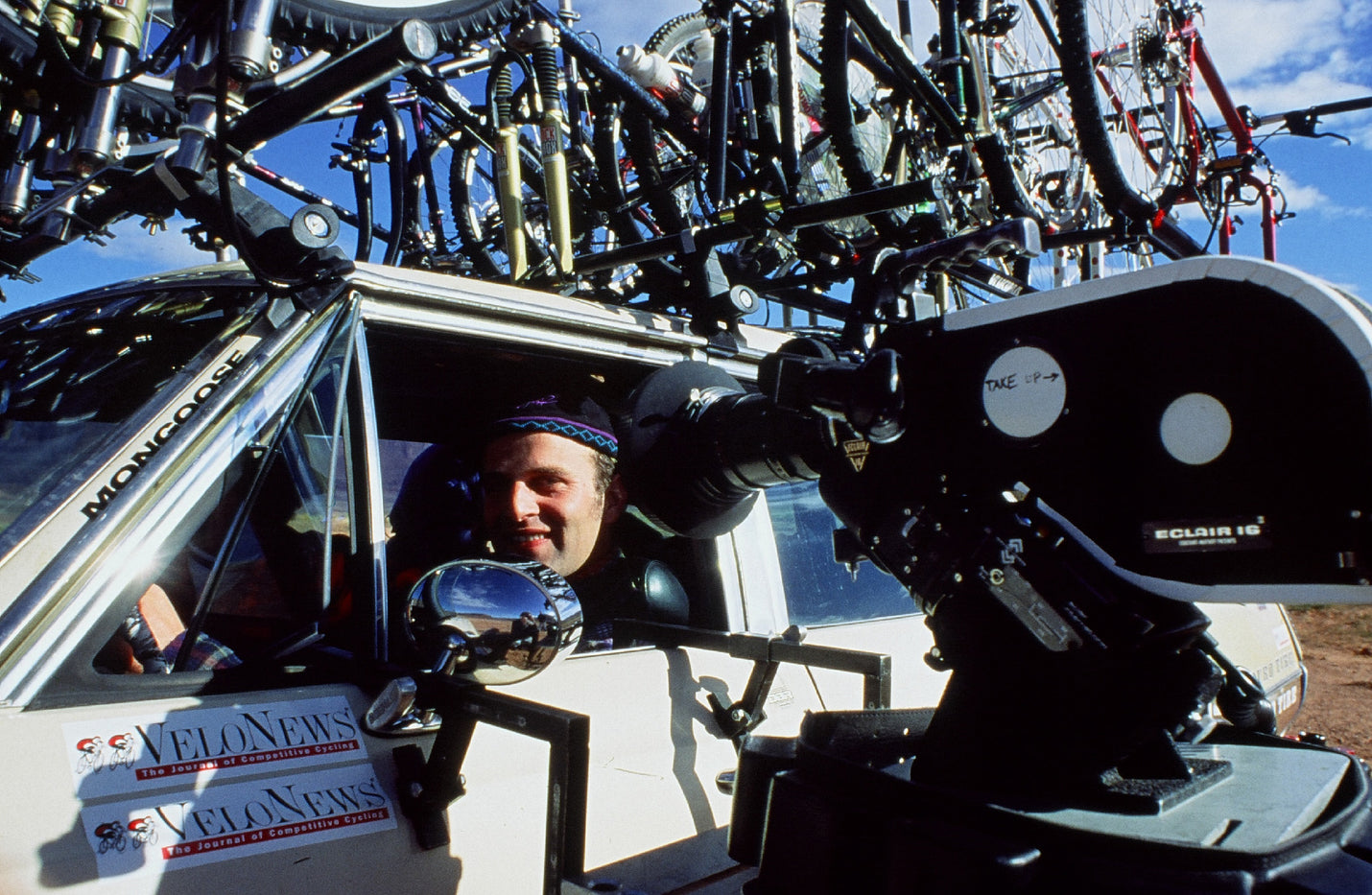

Bill: Film was expensive to shoot—it was like feeding dollar bills into the camera compared to video. I did shoot some video stuff, but those cameras back then were really big, and they were kind of cumbersome. But now the Go-Pro thing and the drones have blown the lid off everything—like the helicopter shot we did, that was crazy stuff. You wouldn’t need to do that now.

Sam: What were the logistics of doing something like that with a helicopter?

Bill: When we did Tread, we had most of the segments—and then we had Hans Rey and Greg Herbold go out to Moab in this car we bought. We had the car out on the road there, and we had this helicopter with this nose mount for the camera. You fly it like you’re playing a video-game, and it’s really easy to get airsick. The pilot practically landed that thing on the roof of the car—it was so close. He said to me, “You don’t think they’d think it’d be funny to hit the brakes right now do you?”

We spent a lot of money on helicopters. By the time you rented the nose-mount, you could usually drop a couple of thousand dollars. And that was back then! We did a crazy shoot once—I was lucky everyone was alive after it—we tried to fly a balloon over the mountains near Vail. The first thing that didn’t work was the camera mounted on the helicopter, and the day just went downhill from there… balloons landed in trees and it was a huge mess. But everybody was still alive.

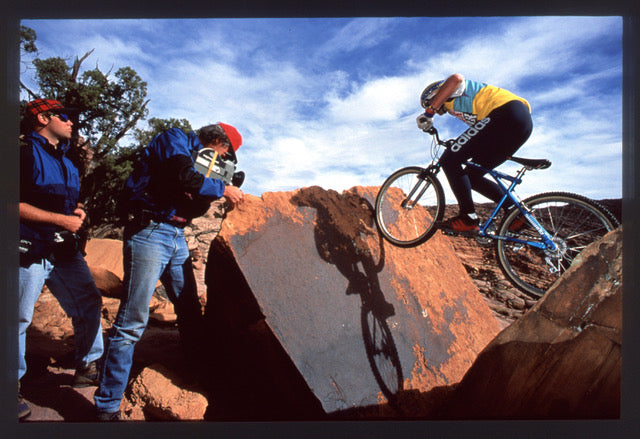

Sam: I’ve seen some of the behind-the-scenes shots of the film where you’ve got 16mm cameras rigged up to bikes for some of the angles. I can’t imagine many other people were doing that at the time.

Bill: That little camera that I had mounted on that bike—I think I had four of those. It was a little French camera called a Beaulieu, and it was probably the smallest 16mm camera around. They weren’t designed to be banged around on bikes, so they were forever jamming. We’d constantly have to stop and put another camera on and reload—we’d spend much more time fiddling with the cameras than we did anything else.

Sam: Like you say, that gear wasn’t designed for what you were doing with it. It was probably made for filming family holidays. You had to think it all up yourself.

Bill: We kind of made it up as we went along. I knew Paul Turner at RockShox pretty well. He had a machine shop, so every now and again I’d go in and say, “Paul, can you make me this little piece of metal that we can clamp onto the side of a helmet?” We clamped the cameras onto cars… I had an underwater housing that I mounted on a kayak… I skied with them… we did all kinds of stuff with those little cameras.

On the other hand, there were these German cameras called Arriflex, and they were tough as nails—you could throw them all over the place and they’d be fine, but they were bigger and chunkier, and you really couldn’t stick them onto the side of a bike.

Sam: Whether you’re making a film about mountain bikes or kayaks or skiing, you’re kind of trying to create an illusion of a constant journey—but I imagine what’s really happening is a fair bit different. What’s the reality of it versus the fantasy you see on screen?

Bill: Well, those still shots of a camera mounted on a bike—they were from a two minute segment that was part of the sequel ReTread. It was up on one of the ski runs near here—this little singletrack that went through a grove of trees, so there was a lot of movement to it. And I think we spent the better part of a day, just doing it and doing it again—maybe mounting the camera in a different place and then doing it again. And maybe getting the camera to work again—or bringing out another camera. And then doing it again. So yeah—you’d spend the whole day doing something like that.

There’s a little segment in Tread—it’s just a POV shot of a bike with all these different angles—and that was me. I went out by myself for half a day, riding on the ‘Slick Rock’ trail outside of Moab, and I would ride a segment, then take the camera off and reposition it. So that was the super simple side of it, and from there it got as crazy as you wanted to.

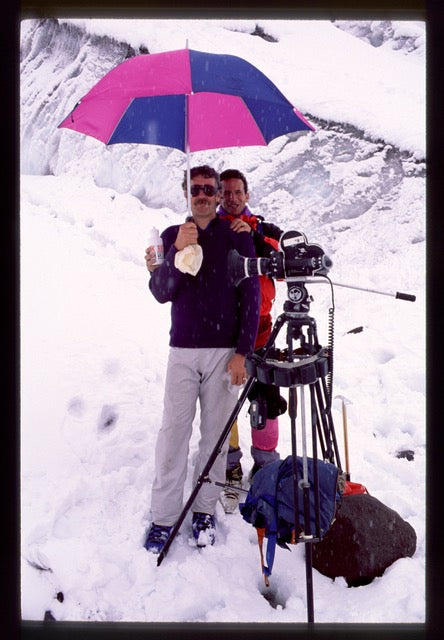

There was a thing where Greg Herbold was riding in the snow. I don’t know if we really planned it or not—but we were up there and the snow condition was perfect for him to ride on. It was hard-pack with some fresh snow on top of it—so he’d climb up and then come back down, and I used to ski with the camera, so I think I skied down with him.

But then we thought, “What we really need to do as part of this is to have him come down from a peak—so we need to fly him up in a helicopter and have him come down something bigger.” So we flew him up on top of this peak, but the snow was so soft he couldn’t even move. So that was a total bust.

Sam: What was your inspiration with this stuff? Your camera work is so much more advanced or inventive than what other people were doing back then.

Bill: My formal training was a fine arts major in school. So looking back at that English football film Goal!—that was beautifully done. I guess that was what spurred me on—we wanted to do something that was visually pretty—something that was nice to look at. I had some other friends who came into film at the same time, and they wanted to do these ‘mind’ things—which wasn’t my thing at all.

Sam: What do you mean by that? Like overly clever stuff?

Bill: Yeah—like dialogue and stuff like that. I was from the art world—I was into the image and how it looked. We’d try to put people into the place where they could be part of the action and what was going on. But I don’t know if we ever sat down and mapped it out… we just did it. There were always ideas you could steal. And actually, I was surprised when the GoPro stuff started coming out at how little they were using those cameras effectively. There were so many places, especially on the bike, where you could mount a camera that small—you could practically mount it on the inside of a wheel.

Sam: Was a lot of those clever angles just a case of winging it and thinking what would look interesting?

Bill: Yeah—you did it enough that you knew what would look good. The first time I really moved a camera around a lot was on skis. I was a pretty good skier—I could actually ski backwards on alpine skis—so I could have someone ski in front of me with the camera pointing uphill and film them on a wide angle lens which created a lot of action and sense of speed.

Later I built this little cage —like a little suitcase I could put the camera in and then run with it—I was the human drone. Especially if a mountain biker was going uphill slow enough, I could run right behind their back wheel to get the shot. I was always trying to think about what was next—what would be a fun and interesting camera angle.

I guess I like to think we maybe brought a photographic element to it that hadn’t really been around a lot. I’d seen some mountain bike stuff that had been shot on video, and that was okay—but everything was just there in front of you, and there wasn’t much to imagine. Those early video cameras were enormous things—you couldn’t mount those on a bike—so we were able to do that and create something that people hadn’t seen before.

Sam: Zooming out a little, by the time you made Tread, mountain biking had gone from a niche subculture to a huge industry. What was that like to be involved with?

Bill: The bike shows at that time were huge. I know the people who started RockShox and the company was doing quite well as were other bicycle related companies who had money to spend on promotion. It created an avenue for us to make a living, but the amount of time I spent chasing down funding was huge—I was constantly hustling.

Sam: The idea of making films and being out there in the action is maybe different to the actual day-to-day stuff that goes on behind the scenes.

Bill: I’m sure I spent half my time chasing money. It was high stress. I quit when I was 57, and part of that had to do with the fact that there was a lot of wear and tear. It wasn’t such a creative process.

One of the ways we were able to get out of it was that we got into the stock footage world at almost the perfect time. We got into it with a company in New York in the early 90s, and we rode that wave when people wanted stuff shot on film. Those high-def RED cameras weren’t out at the time, so they wanted mountain biking shots, shot on film, to put in beer commercials. And we probably had the largest collection of mountain bike footage shot on film of anyone in the world—so it was a pretty good deal.

Sam: So someone’s making a Gillette advert for some new razor blade, they’d go to you for a few seconds of footage of someone riding down a mountain?

Bill: Yeah! If you see a beer commercial with a couple of guys out on mountain bikes, they didn’t send the ad agency guys out to do that—they just went and bought it.

Sam: I never thought of that but it makes a lot of sense. Changing subject a little, was there an overarching thing you were trying to show with all your outdoor films? Were you trying to show the beauty of these activities?

Bill: Yeah I think it was that… rather than just standing back and documenting the action. Do you remember the artist Christo who went around wrapping buildings? I worked with a woman once who worked for them making documentary films—and she had an interesting observation about my work. She said that they’d just plonk the camera down and let whatever happened in front of them happen, whereas on the other hand, I’d create the action with the camera. And I suppose that was the difference. I was trying to bring people into the action.

The technology now has definitely brought the viewer into the driver’s seat—I was watching some downhill skiing the other day and the camera was right on top of one of the skiers—you really felt how fast they were going.

But I don’t know what the next level is with this kind of thing. My good friend who I made that kayak film with, his son is a camera operator and he has this fleet of drones and all this stuff. Now everyone’s got all that, it’s like, “What’s going to happen next?” And I’ve got no idea what that’ll be.

Sam: There’s always the hunt for the next thing. But even with all this fancy gear that’s around now, are the core tenets of filmmaking pretty much the same as they were back when you started in the ‘60s?

Bill: Yeah, a camera is just a tool. It’s like a guitar—it depends on who’s playing it.

Thanks to Sam Waller for the interview.

See what Bill is up to these days here.