In 2011 Foster Huntington quit his New York fashion job, bought an old VW Vanagon (the US equivalent of a T3) and hit the highway. Whilst the idea of life on the road was by no means a new one, the way he documented his travels instantly set him apart from those who came before—utilising tools like Instagram (back before it became the mind-melting hellscape it is today) and the humble blog to give people around the globe a window into his four-wheeled world.

With his sun-soaked snaps and straight-up tales from the open road, his so-called ‘#vanlife’ (the now omnipresent term he casually coined), didn’t just look appealing, it looked attainable—and the motorhome industry probably owes him a fair bit of commission for the amount of campers he helped flog.

Since then, even as the concept of living on four wheels has entered the mainstream, he’s only continued to go against the grain, printing books, building treehouses and devoting serious time to the overlooked art of stop-motion animation. Here’s an interview with him about living in the treetops, finding fulfilment in the modern age and why VHS wins over Netflix.

Sam: From what I’ve read about your life it seems like there’s been a few chapters. You were working for Ralph Lauren when you were pretty young, but left that to drive around in vans, but then just as vans became more popular, you built a treehouse. You’re always one move ahead.

Foster: Yeah—I realised I didn’t want to work in fashion, and I wanted to work outside. I’ll try something to figure out whether I like it or I don’t like it—and then if I don’t like it, I’ll transition out of it. Sometimes more abruptly than others.

Sam: Not many people are willing to do that.

Foster: Yeah, I definitely think people don’t let themselves change their minds enough—on what they like, or they don’t like. I guess they get wrapped up with the idea that something is their identity—and therefore they can’t change it. But I try not to let anything become my identity to that point, because once you let something become your identity, then you can’t change your mind.

Sam: I don’t know if you’d agree, but it felt like at one point you were almost the poster boy for the modern van movement. Is that a strange thing to live with?

Foster: I never really felt that way, because when I was really interested in doing the van thing, no one really cared. It wasn’t until years later that people were like, “Oh yeah, that made sense what you were trying to do.”

I went to this van trade show recently. It was purely happenstance—I was on a roadtrip with my dad, and I was trying to get my dad to get a van—and I looked online and there was a tradeshow right where we were driving though, so we went to check it out. And that was a little surreal—it wasn’t a thing ten years ago, and now it’s literally a billion dollar industry. It was funny seeing the name ‘vanlife’ everywhere.

I don’t think I invented it, or was the poster child of it, I was just at this confluence of new technology and had the skills and wherewithal to document it in a way that was new.

Sam: Why do you think there has been such a move to vans and alternative ways of living in the last ten years?

Foster: I think a lot of it is from socioeconomic or generational things—Millennials and young people just don’t have the kind of financial opportunities that Gen X and Boomers had. So just coming of age in very stagnant economic times, if your career is amazing and you're making a load of money, you’re going to stay with that, but if you’re just floundering, you’re going to reassess what you’re doing more.

Sam: What made you want to park up your van and build a treehouse?

Foster: I guess in my creative arc, I kind of got to the point where I wanted to do more than take photos. I didn’t want my life to just be travelling and documenting that. I had friends who were photographers, and I saw that they were captured by their own success, and the only way they could make money was by travelling all the time. I didn’t want travelling to be this thing I had to do to make a living—I love to travel, and I found a way to make money so I could do it, but I didn’t want the roles to be reversed.

Also I was interested in doing video stuff, and to do video stuff in any meaningful way—and I’m not talking about vlogging or what you see on YouTube—if you want to do video in a considered way, it requires more infrastructure than I was capable of doing in my van at the time. So that’s why I set up a home base.

Sam: How did you go about making the treehouse? What’s the logistics of something like that?

Foster: It’s similar to building any kind of structure, except that it doesn’t have a traditional foundation… it’s in a tree. So I approached it the same way I’d approach building a studio or a house. I hired an engineer to design a platform that was rated for a certain amount of weight, and then it just became a fabrication project. It’s similar to building anything—you figure out your foundation, you figure out the plan, and then you execute it.

Sam: You're making this sound pretty easy. I imagine building it is a bit more of a hassle.

Foster: Yeah—building it was way more complicated. I spent seven months in a climbing harness up in a tree. You get used to it, but it’s totally uncomfortable at first, and everything becomes like yoga. But in terms of the strategy… it’s the same as building anything.

Sam: When you’re doing some of these projects that are kind of against the grain, are there points where you think, “What am I doing?”

Foster: Not really. I’m one of those people who once they have an idea, is really committed to it. And that’s the only way I’m able to get shit done. If you allow yourself to question what you’re doing, it’s not going to work out. I guess in the lead-up in deciding what I’m going to do, I’ll weigh up the cons and try to imagine the hurdles and what the challenges are going to be—and then I decide whether I’m going to do it or not. There are lots of things I decide not to do.

Sam: What like? What was too far out?

Foster: It wasn’t that it was too far out, but right after I finished the treehouse I had this idea to buy a sailboat and totally overhaul it and then travel the world in it with a bunch of friends. I had money saved up from doing the photobook, but I just came to the realisation that I didn’t want to jump the shark—making a bigger project that’s even more of a spectacle. I didn’t want to keep having to do that. I thought, “If I do this, then what am I going to do next?” So that’s when I decided to build the studio. Instead of making these fantastic versions of reality, I’d rather make things that are totally made up.

Sam: I suppose it’s like David Blaine. You stand on a pillar for 40 days, the next year you’ve got to be encased in ice for 50 days…

Foster: Exactly. You’re in this game where you’re constantly having to do something to one-up yourself and have a photo to post everyday on Instagram and make all this content. I just didn’t want to be wrapped up in that cycle. I’d rather make things that were less connected to reality, and have it be less about me. I don’t want everything I make to be about me.

Sam: I suppose that’s what’s happening in the mainstream—but most of the interesting things happen on the fringes anyway. Is it about creating a community, rather than this spectator system where we just swallow up what we’re fed?

Foster: I do think people will want to opt out of it and embrace their own form of curation, but it’s really hard to be successful financially and create in that system. The creative industry is going the way of the dodo, unless people make a conscious effort to circumvent the system and support people directly, whether that’s on Patreon or SubStack or by buying their stuff. You can’t rely on companies or corporations to do that.

It’s definitely about having those communities of creatives. I remember a time when that existed on any platform—on Tumblr, on Vimeo, on Instagram or blogging. Before corporations or the masses accept anything, there’s a small group of people doing it just because they like to do it. Then by the time those things become economically viable those people have largely left and moved on.

Sam: Yeah—the early instigators keep moving. What’s your next thing?

Foster: I’d say that my biggest talent isn’t necessarily being a good photographer or writer. I can get by, but my ability has been to anticipate what’s happening, and move before other people move. When Instagram came out, I was like, “This is amazing.” I saw the future in terms of creating content like that. And then with Movie Mountain, the idea was, “Everything you see on social media is contrived, so why not accept that and make things that are totally ridiculous,” instead of making these faux-documentaries. That’s why I got into doing stop-motion. But what next? I don’t know. I spend most of my time thinking about what the world is going to look like, and where I fit in—and I still don’t know what the world is going to look like.

I think it’s going to be super different. It’ll be interesting. We’ve already seen it happening where people are oversaturated by social media content. And once AI takes over, people are going to be so tired of it. It’s no longer difficult to make a cool image—any brand can have a photoshoot—so nothing really stands out. So I think people will be more interested in doing events—exclusive things that only happen offline.

Sam: Talking of being oversaturated, how do you shut off from this stuff? You seem to live quite a balanced life.

Foster: I love camping, I like to go hunting, I like to go hiking. I try to spend time outside where I’m not on my phone or on my laptop, but it is difficult because your phone is like crack, it’s like instant dopamine.

Sam: It’s not easy. You’ve got a pretty impressive VHS collection too. Is that a way to stay more engaged in the present and avoid just clicking and scrolling?

Foster: Yeah—instead of watching a movie on Netflix every night, I like to watch a VHS. I like to watch things in that medium because you can really assess it for what the story is, as opposed to being wowed by the special effects. Last night I watched this movie called All the Pretty Horses which Billy Bob Thornton made. It’s an adaptation of a Cormac McCarthy book. And the movie is dogshit, but I love the book, so it’s interesting to read a book and then watch a book and see how it lines up.

Sam: Is the hunt part of it too? Going out and trying to find a video is more interesting than scrolling through Netflix.

Foster: Yeah—I like finding weird shit. I’m always looking in thrift stores for cool stuff. It’s fun.

Sam: Do you think as technology goes so far one way, you almost have to react against it by going further the other way? You’re in a treehouse watching old video tapes.

Foster: Yeah, countercultures emerge against the status quo. I imagine that will manifest in all sorts of different ways.

Sam: I like your photos and the way that they show nature, but in a way I can relate to. Is there anything specific you’re trying to capture or show with them? What do you think makes a good photo?

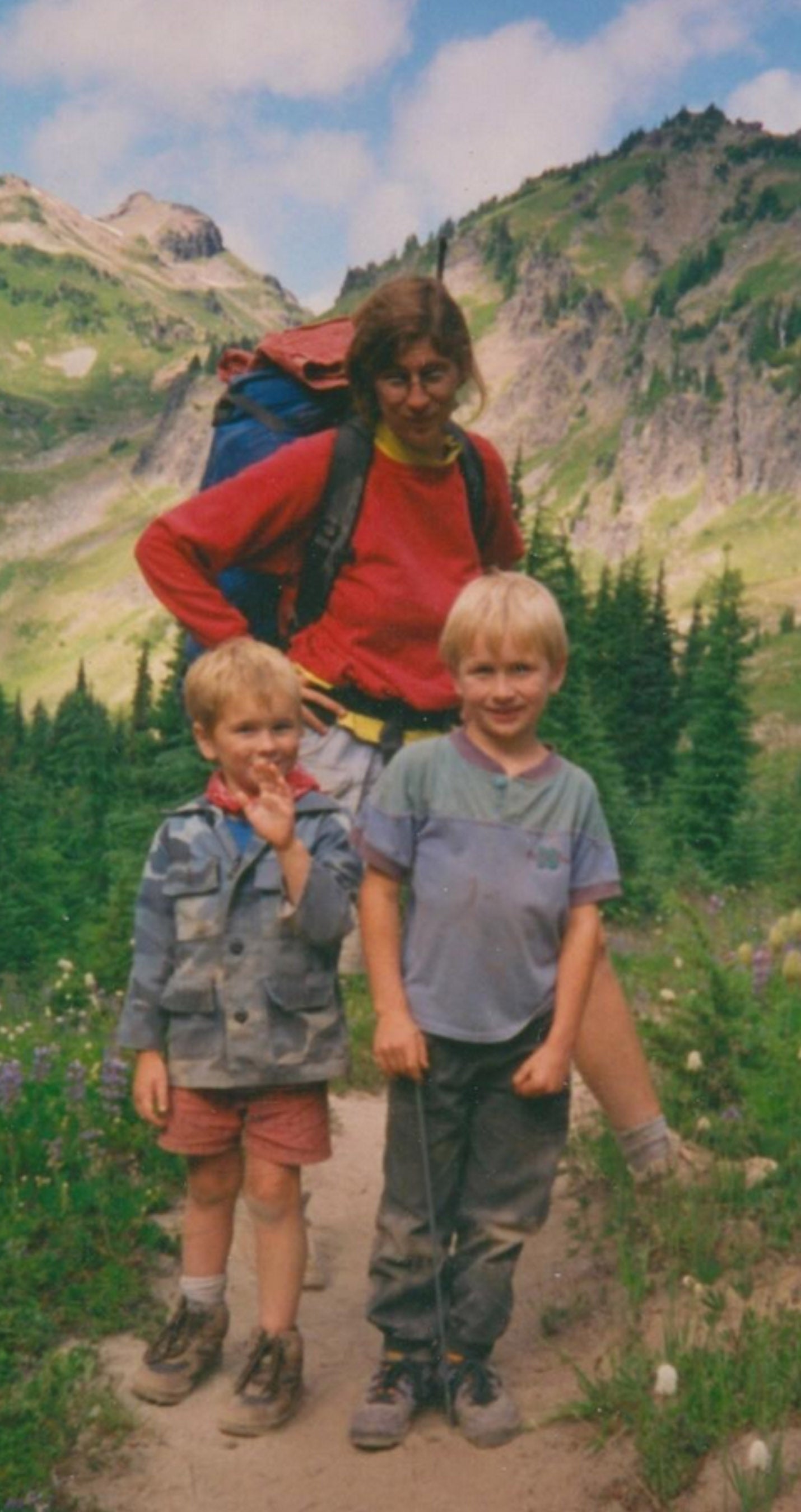

Foster: I spent a lot of my childhood outside in the woods of Washington and the Mountains of Oregon. When I got to the age where I started becoming aesthetically aware, I rarely saw photos or videos that captured the parts of the outdoors that made me want to be a part of it, out there camping and exploring. When I started taking photos, I immediately tried bridging this gap. To me a good photo is something that's novel—either in composition or subject matter—that takes you to another place.

Sam: From your photographs to your writing to your films, is there anything that ties it all together? Is there a link or a theme that runs through them?

Foster: I would say that they are definitely all from my perspective and stem from the desire of an observer to share things that they feel drawn to that don't necessarily get the attention they think they deserve.

Sam: That makes sense. Change of subject here, but you know Lloyd Kahn don’t you? I read something somewhere about how he was a big inspiration to you. Is it important to have people like that to be influenced by when you’re going off the beaten path?

Foster: Yeah, I think there are very few people who march to the beat of their own drum for the long run, and still find a way to make media—and Lloyd is definitely one of those people. His instincts are fantastic. He’s a treasure. He’s amazing. I like people who listen to what they believe, as opposed to just doing what’s expected of them. A lot of people are dead that I like, like Hunter S Thompson. I think he’s the person I’ve spent the most time reading and thinking about. Werner Herzog is another person who I think is really amazing. And Jodorowsky. These wild individuals who don’t compromise.

Sam: That’s a pretty rare trait. Not many people step outside the norm. How do you fight past that?

Foster: I think it’s incredibly difficult to maintain that. It’s very isolating and lonely. In order to have individual opinions and be committed to what you’re doing, you’ve got to be committed to it. Another writer I’ve been interested in the last few years is Ed Abbey who wrote the Monkey Wrench Gang and Desert Solitaire. He’s a pretty amazing thinker who ruffled some feathers. You can learn from all sorts of different people—you don’t even necessarily have to agree with them on everything.

Sam: I think people are finally realising that now. Or at least I hope they are.

Foster: I sure hope so. That’s why I think podcasts are seen as such a valuable or powerful medium, because you can connect with people directly and listen to what they’re saying in a way that feels more real. There’s a reason why people don’t listen to news media anymore, and they listen to podcasts. But the question is how do you find a balance in making stuff that you believe is a true representation of what you’re observing, but doing it in a way that’s interesting and beautiful? Because while podcasts are amazing, they don’t satisfy any of my aesthetic sensibilities. It’s not like I think they’re beautiful or that they’re art.

Sam: They’re too long and unedited.

Foster: Yeah, they satisfy a different urge. It’s the same thing with YouTube. I love watching YouTube videos, but I never watch one and think, “Damn, this is amazing,” the same way I do when I watch The Good, The Bad and The Ugly, and I’m like, “Holy shit, this is a work of art.” I think the answer is out there somewhere, but as someone who appreciates aesthetics and subversion, I hope there’s a way for people to make subversive stuff and still make a living doing it.

Sam: I suppose you’re a good example of someone who has managed to do it on your own terms. With things like building your own home, do you think that’s something more people could be doing? Could that ever be a large-scale thing?

Foster: It’s difficult because it’s so much more expensive than it ever has been before. If you talk to people like Lloyd Kahn or some of his friends, they were involved in that initial 60s counterculture, if you talk to them and hear their experiences, it was cheap! It cost less money to zone out and check out than it does today. It’s way harder now. You used to be able to buy a piece of property for $10,000 and build a house, but now it’s so much more difficult to do that. I think there are opportunities, but it’s a lot more difficult today than a lot of examples we look to from yesterday. I’d say I was a global pessimist, but a local optimist. I think you can do beautiful things, on a small scale. If you’re too concerned about the world at large, you’re just going to get lost in the sauce.

Sam: As someone who’s spent a lot of time driving around in a van, and now lives in a treehouse, what are your thoughts on boredom? Is it important?

Foster: I definitely think confronting your imagination and what goes on in your brain is good—either consciously or subconsciously removing those distractions from your life, even for a brief period can be fantastic and lead to good things. Like going on a camping trip, or leaving your phone not by your bed, or reading a book the old fashioned way, or watching a movie the old fashioned way, or sitting by a campfire. And some of this stuff is relatively accessible.

We live in a generation and a time where people are completely consumed with convenience and they want to have things without compromise, but you’ve got to make some tough decisions about how you want to live. I have so many friends who are like, “Oh my god, I want to buy a house.” There are beautiful cool houses available, but they’re like, “But I live in LA” or “I live in London.” and you’re not finding a house in those places. You need to be cool with the fact you might live out in the woods, or in an old town. The dream is still alive, but you’re going to have to make some tough choices about where it is. And I think that’s just a metaphor for lots of things in life.

Sam: That’s got to be a knock-on effect of social media, hasn’t it?

Foster: Exactly. They want to have this life they’ve seen on Instagram, but that’s merely an illusion. And then second of all, that’s not you—people are unique individuals, so why not appreciate the stuff that you have now? It’s no secret that the most developed countries are often the least happy, and transversely, the least developed countries are often happy. For example, Nicaragua has the highest happiest quota of any countries in the Western Hemisphere, but is also the poorest, so how do you rectify those things? If you buy into the notion of consumerism, it would be totally different.

Sam: Big question, but where does real fulfilment come from if it doesn’t come from buying cool stuff?

Foster: I think that humans have had similar intellectual capability for a million or two million years, and during that time we’ve evolved to be happy and to get gratification from things such as building your own structure or getting your own food. These kinds of basic things that everybody is insanely disconnected from now because they’re not efficient and can’t be done at scale. If you do shit that people have done for millions of years like catch your own meal or grow your own food or create art, just for the sake of doing it, then you’re going to get some kind of gratification from that. And that’s what Lloyd Kahn is all about, to tie it back to him. He eats roadkill, he makes his own structures, he grows his own food. It’s not that difficult, it’s just kind of a nuisance.

Sam: Yeah, life is surprisingly basic. Rounding this off, how do you judge success? Is it money, is it numbers, or is it something vaguer—something harder to define?

Foster: I will say that by the time the money arrives, the battle has been fought and won. Money is not an indication of creative success. If you want to be successful financially, you’re the person that rips off other ideas and just waits around for it to be commercially viable. So I’d encourage people not to think about creativity that way. At first creative ideas are not necessarily accepted. They don’t get a ton of likes and they don’t immediately reap financial rewards. It takes time. You’ve got to have the patience to be like, “Okay, this works, I like this, this appeals to my inner child.” And if it validates that, then it’s probably cool.

Thanks to Foster Huntington for the words and to Sam Waller for the questions.

Subscribe to Fosters excellent YouTube channel here:

Movie Mountain

Follow Foster on Instagram:

Subscribe to Fosters Substack here: