Everyone’s definition of adventure is slightly different. Most are content with an afternoon hike—some prefer a week in the Alps, and for a few brave souls like Jo Scarr, it means something a little bolder—like driving a Land Rover all the way to the Himalayas and hiking straight into the unknown.

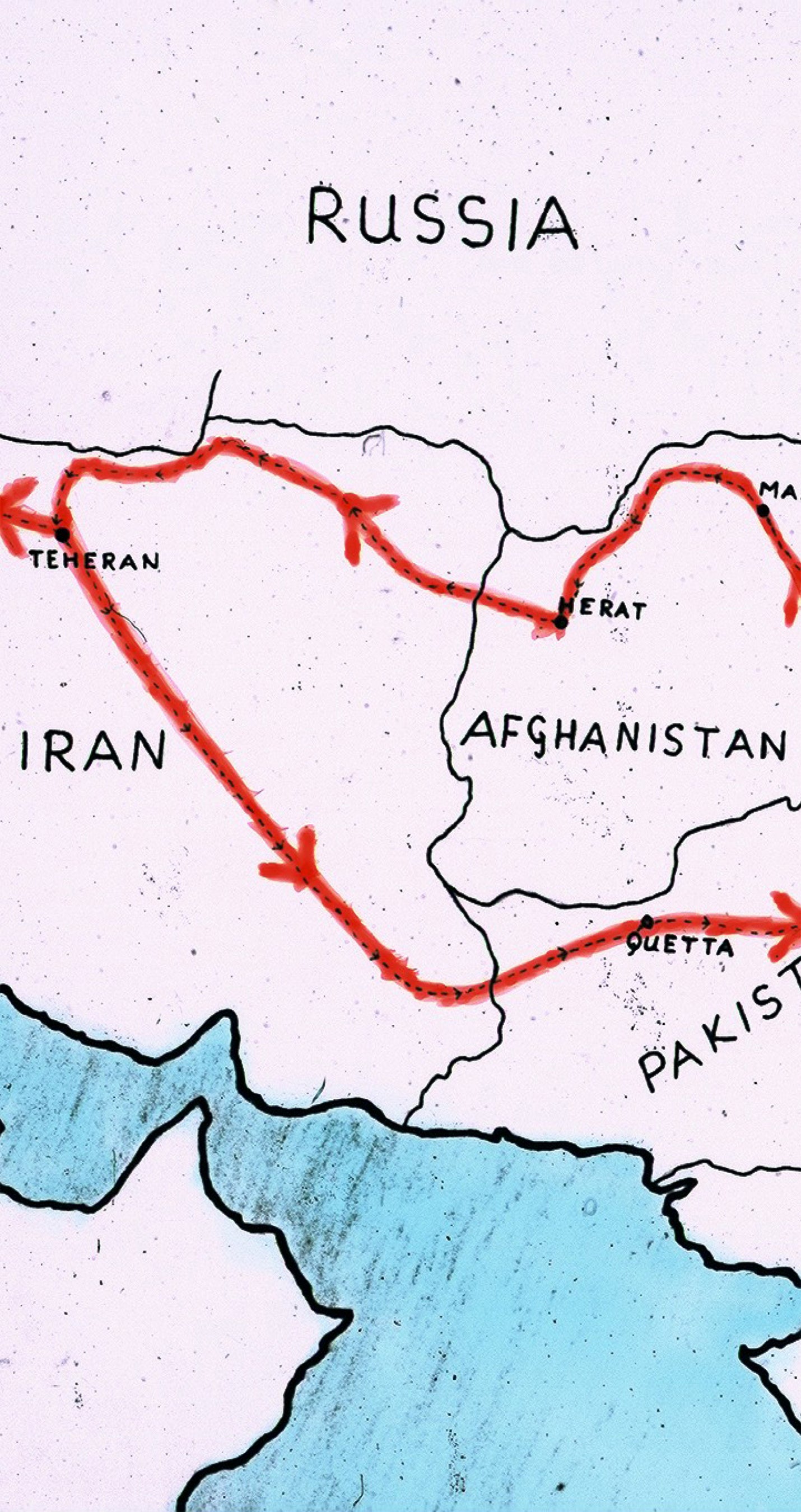

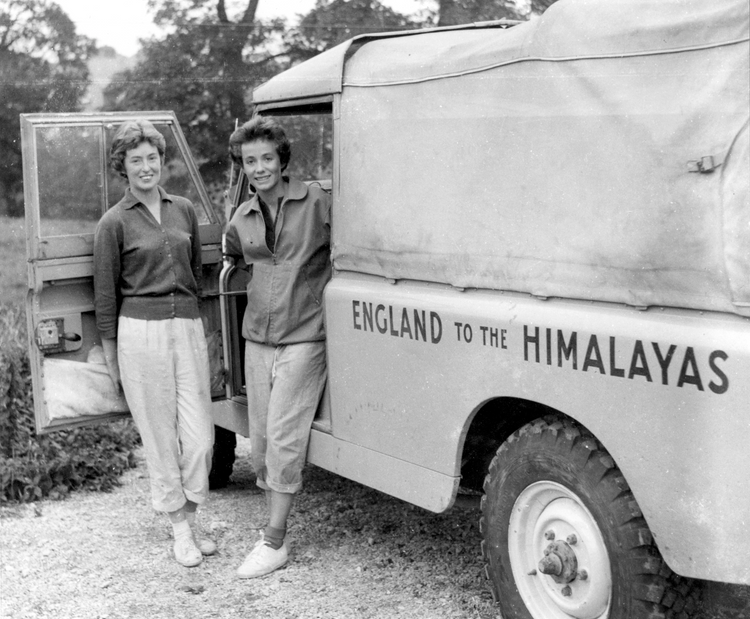

Setting off in the summer of 1961, the Women’s Kulu Expedition saw Jo and her friend Barbara Spark—both just in their early 20s at the time—pack up their home-made tent and drive from North Wales right across Europe and into Asia, before parking up in the Indian Himalayas to explore an uncharted region of the Kullu Valley (the second ‘l’ was added later).

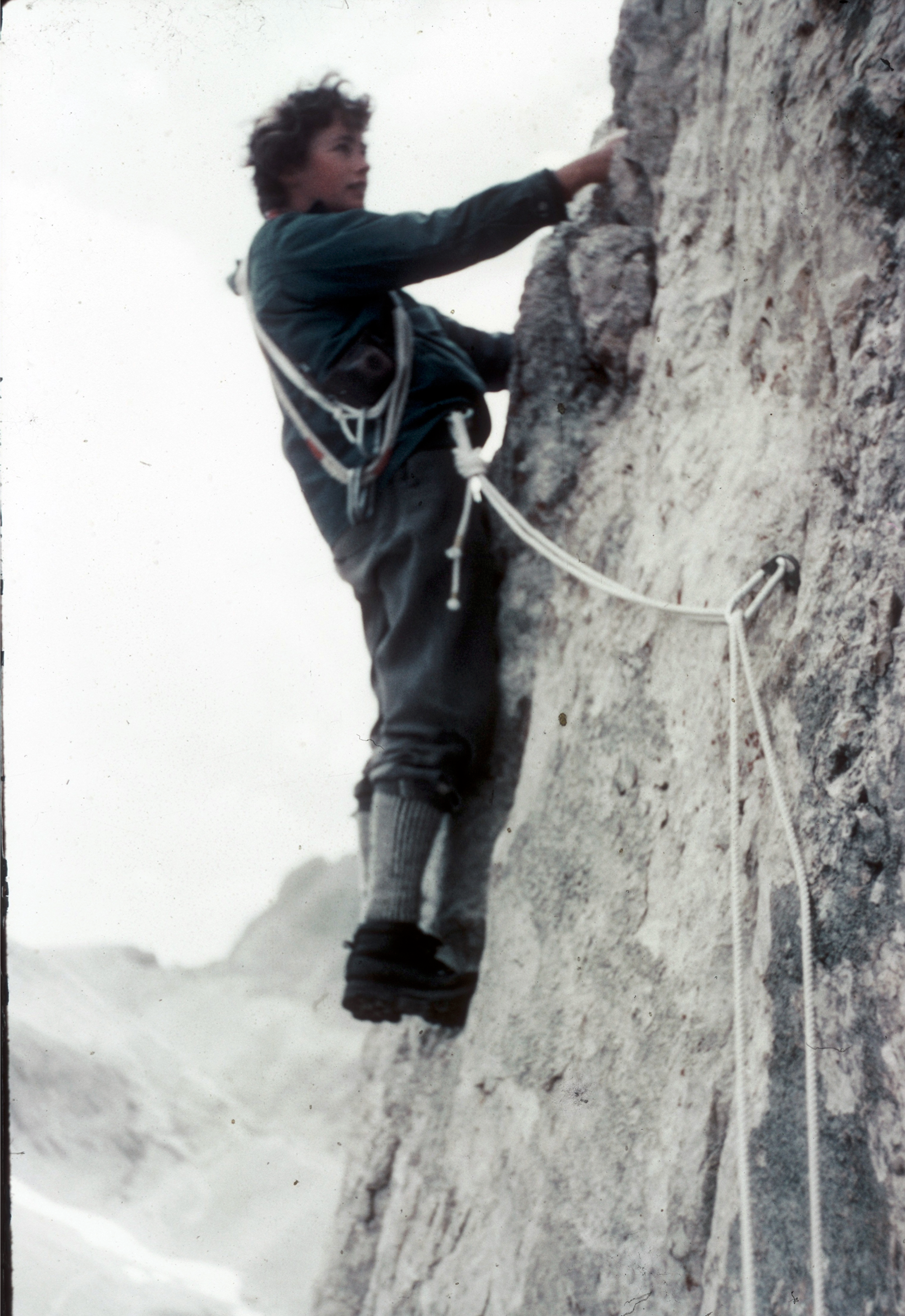

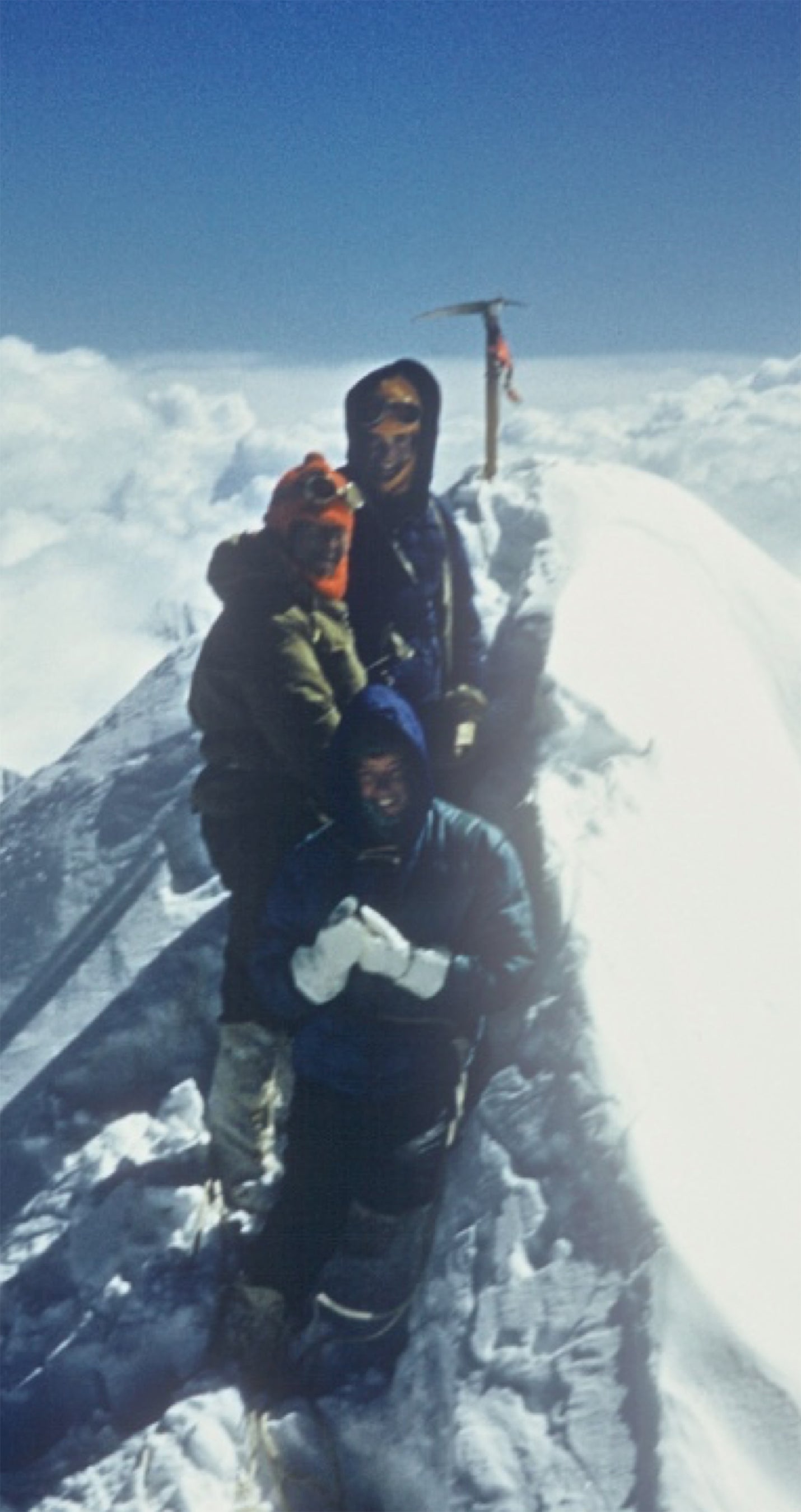

In the weeks that followed they not only mapped out an area where no human beings had set foot before but, along with their porters, they scaled mountains that people didn’t even know existed—reaching untouched summits over 6,000 metres high. A year later, more first ascents followed when they joined the all-female British Jagdula Expedition—exploring the isolated Kanjiroba Himal region of Nepal and scaling no less than seven unclimbed peaks.

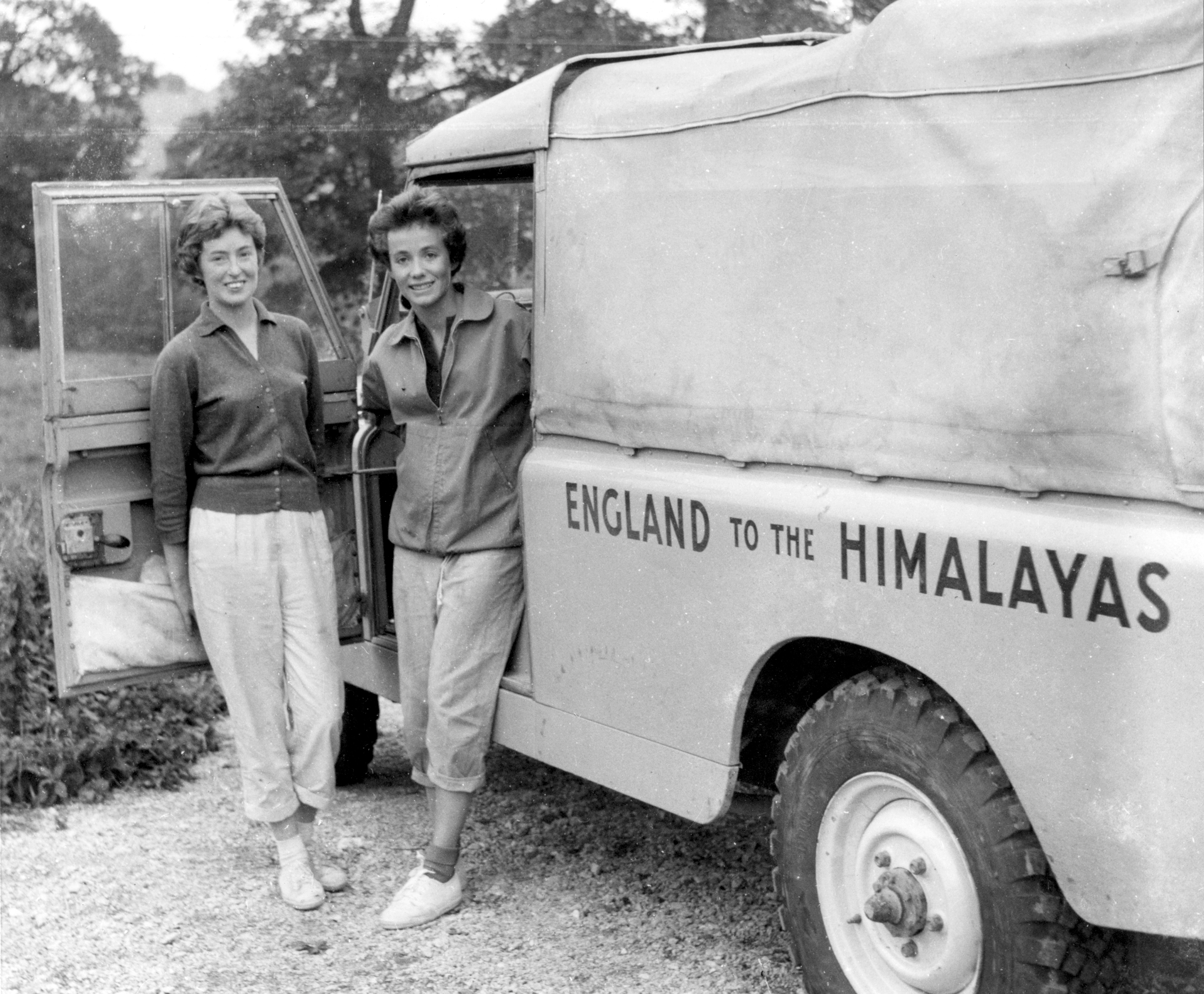

And this is just the tip of the mountain, with Jo’s CV also boasting the first female lead of the notorious Cenotaph Corner in Llanberis Pass and a lifetime of pioneering archeology work. She also happens to live just down the road from Outsiders buyer Josh—which is why one Saturday morning we found ourselves sat in the ‘mountain room’ of the 500 year old house she lives in with her husband Nigel Peacock (another legendary climber), enjoying a cup of tea and a plate of biscuits as they regaled stories of hiking in the Himalayas, cooking moths and abseiling down university buildings…

Sam: Going right back to the start, how did you get into climbing in the first place?

Jo: I was useless at sports at school because I had no eye for a ball—but I was a great reader. I read a book in Boston Spa library—Nansen’s Farthest North, which is about polar exploration, and I thought, “That’s what I want to do in life—I want to discover things—go to places that no human beings have been to before.” When I went to university I didn’t think I’d be able to fulfil this ambition for discovery, but then I got into climbing by accident.

I’d gone to Leeds University for a couple of semesters before going to Cambridge—because you had to be 19 to go to Cambridge—and the only person I knew at Leeds happened to be a climber. He was the secretary of the climbing club, which had both male and female members, and they were always talking about climbing—saying things like “peeling off,” and “hanging on,” and all this stuff.

Eventually they said for me to come out with them to Almscliffe Crag—so I went out just to watch, wearing a wide skirt and sandals, but by the end of the afternoon they persuaded me to climb. I was only following, but it went okay, and from then I started going up to the Lake District and climbing around the Yorkshire crags.

Sam: And from there you were hooked?

Jo: I really enjoyed it. We’d also go caving—and I remember going up to the Yorkshire Dales when there was snow on the ground—and when we walked across the moors we managed to find new caves because the warm air from the cave would melt the snow—so that was quite exciting.

From there I went to Cambridge, and discovered I couldn’t join the men’s club. There was a ladies club called the Magogs, which was pretty defunct with just two members, but I linked up with them. We’d often go up to the Peak District, climbing in Derbyshire as well as North Wales and Scotland—seeing the New Year in on Ben Nevis one year with a lot of Scotsmen.

Were you two involved with the night climbing stuff at Cambridge? There’s a huge history of students climbing the old buildings around the university there isn’t there?

Nigel: Yes. I think we were just a bit nutty frankly. I can’t remember how we got into it in the first place.

Jo: I wasn’t a night climber—except occasionally I had to climb over a fence to get in or out of a college after hours—and I used to abseil out of my window occasionally as I was on the top floor. It was good old fashioned architecture, so you could put your rope down the middle of the stone window frame.

Nigel: With night climbing you assumed that the powers that be didn’t know what you were doing—as if you got nailed you’d be sent down no doubt about that—but I remember getting back to my room one lunch time to find this letter from the Dean, requesting my presence in his office. So I put on a tie and a gown and went around. Overnight a chamber pot and a couple of bras had appeared on the top of the college, so I thought I was going to get blamed for that. When I went in he stood to attention and said, “Peacock, the college does not believe that you’re responsible for these items, but it would be delighted if you could remove them.” So I did my only daylight climb, going right to the top and bringing these things down. I suddenly realised that the Dean knew exactly what was going on. I wonder how much I saved the college in steeplejack fees?

Sam: Wasn’t there a car on the roof once too?

Jo: That happened in our time, and we know who did it.

Sam: How did they do that?

Nigel: They were a bunch of engineers led by an army bloke. It was a baby Austin which they put up on the Senate House. They’d taken the engine out to get it lighter. I don’t know how they did it. The Senate House was right next door to part of another college, and the gap between them was about eight feet—and one of the feats that most people didn’t dare do as you were three stories up, was to jump from one to the other. I never did that—I wasn’t that daft.

Sam: Around this time you were the first woman to lead the legendary Welsh trad climb, Cenotaph Corner, weren’t you Jo? What was your drive for doing that kind of thing?

Jo: I think it was because I was brought up with two older brothers close in age. They were going to have careers, but I didn’t just want to stay home. My father just wanted me to marry a wealthy Yorkshireman and stay put, but I didn’t want to do that. Regarding the actual rock climbing, I didn’t enjoy being at the bottom end of the rope, so I preferred to eventually lead. I realised after a while that I had reached my limit with things like leading Cenotaph Corner as I didn’t have any strength in my arms. I’ve never been able to do a pull-up in my life—so I wouldn’t be any good on the indoor walls people climb on nowadays. Also the equipment wasn’t very good in those days.

Nigel said that in his last year at Cambridge no less than eight of his fellow climbers lost their lives—either climbing or in the Himalayas. If you fell off a climb then the chances of surviving weren’t good. Frank Butler, the guy who introduced me to climbing at Leeds University was found dead at the bottom of one of the Welsh cliffs with his female companion. Sometimes people would put ropes over a rounded rock, and it would pull out from underneath—so that’s maybe what happened.

Sam: I’ve seen old videos of Cenotaph Corner where people would wedge pebbles into the cracks to support their ropes. That seems pretty precarious.

Nigel: Because we didn’t use pitons we’d use them instead. It was a way of getting a decent belay rather than just putting a rope over a spike of rock and hoping it wouldn’t just snap off.

Sam: There’s a lot of trust there. When you were climbing at that time was it that thing of being young and fearless?

Jo: If you didn’t have children you didn’t regard the possibility of a fall quite as seriously as you did later.

Nigel: I think there’s another aspect too—if you read Peter Pan there’s a bit where he’s marooned on a rock and one of the things he says is, “To die would be an awfully big adventure.” And I think in your early twenties that’s true. I don’t think many of us thought that consciously, but there is something rather heroic about that idea.

Sam: And was it the times too? Coming out of WW2 where people had been so close to death, was there almost a thirst for risk and adventure? From motorcycles to climbing it seems like that was an era of adrenaline.

Nigel: Absolutely. Going off on a tangent, but I see these fantastic motorbikes around now—and I’ve got to admit that it would be fun to go on one—but we didn’t just ride around on a Sunday afternoon. I had an AJS 350 and I rode that thing out to the Alps three times with a rucksack with all my gear inside. We used them for epic expeditions. My first wife who was as equally adventurous as Jo, she had a little Lambretta scooter, and one summer rode the thing with a friend of hers up to the Arctic Circle, and then she turned around and rode it right down to Marseille. She wasn't allowed to take it on the boat to Tunisia where she wanted to go, so she left her friend there and came up to Chamonix, met up with me where we did some climbing, and then we set off across France, sleeping in barns and under haystacks.

Sam: I suppose that brings us nicely to your expedition Jo. What made you want to drive a Land Rover to the Himalayas?

Jo: At the end of my time at Cambridge I did enough to get a 2:1, but in those days you had to get a first to do a masters or a PHD, which is what I wanted to do, so I gave up academia altogether and decided to become a climbing instructor. I was given a job at Plas Y Brenin as their first female climbing instructor—I was there for two years, doing lots of instructing and climbing my own stuff—and there I met Barbara Spark who was a teacher at a high school in Liverpool, when she brought some of her pupils up.

We started climbing together, going to the Alps—climbing this and that—and then eventually both of us were feeling restless and decided to give up our jobs and go to the Himalayas. We weren’t very confident, and we knew it was going to be expensive, so we put in for grants, and we got one from the Mount Everest Foundation who had remarkable faith in the two of us heading off to climb unclimbed peaks in the Indian Himalayas.

Nigel: There’s a lovely little story there. You can imagine Jo, who was then 22, going to see the Everest Committee, and one of these bearded guys said, “You’re a little small to be going to the Himalayas aren’t you?” And she said, “Well, it’s a very small expedition.”

Sam :I was going to ask about that—what was the general attitude to a female climber back then?

Jo: Things were changing. When I started at Plas Y Brenin in 1959 I was the first female instructor, and there were very few female climbers. For our trip to the Himalayas we called ourselves the Women’s Kulu Expedition 1961. We wrote to all the companies to ask for free goods as we couldn’t afford much, and we got given a lot of stuff—including things like cosmetics from Elizabeth Arden to try out. We also did articles for women’s magazines, but the women's stuff was just beginning really. You couldn’t go on a mixed expedition then—because the authorities thought they were just holidays.

Josh: And you made all your own gear didn’t you?

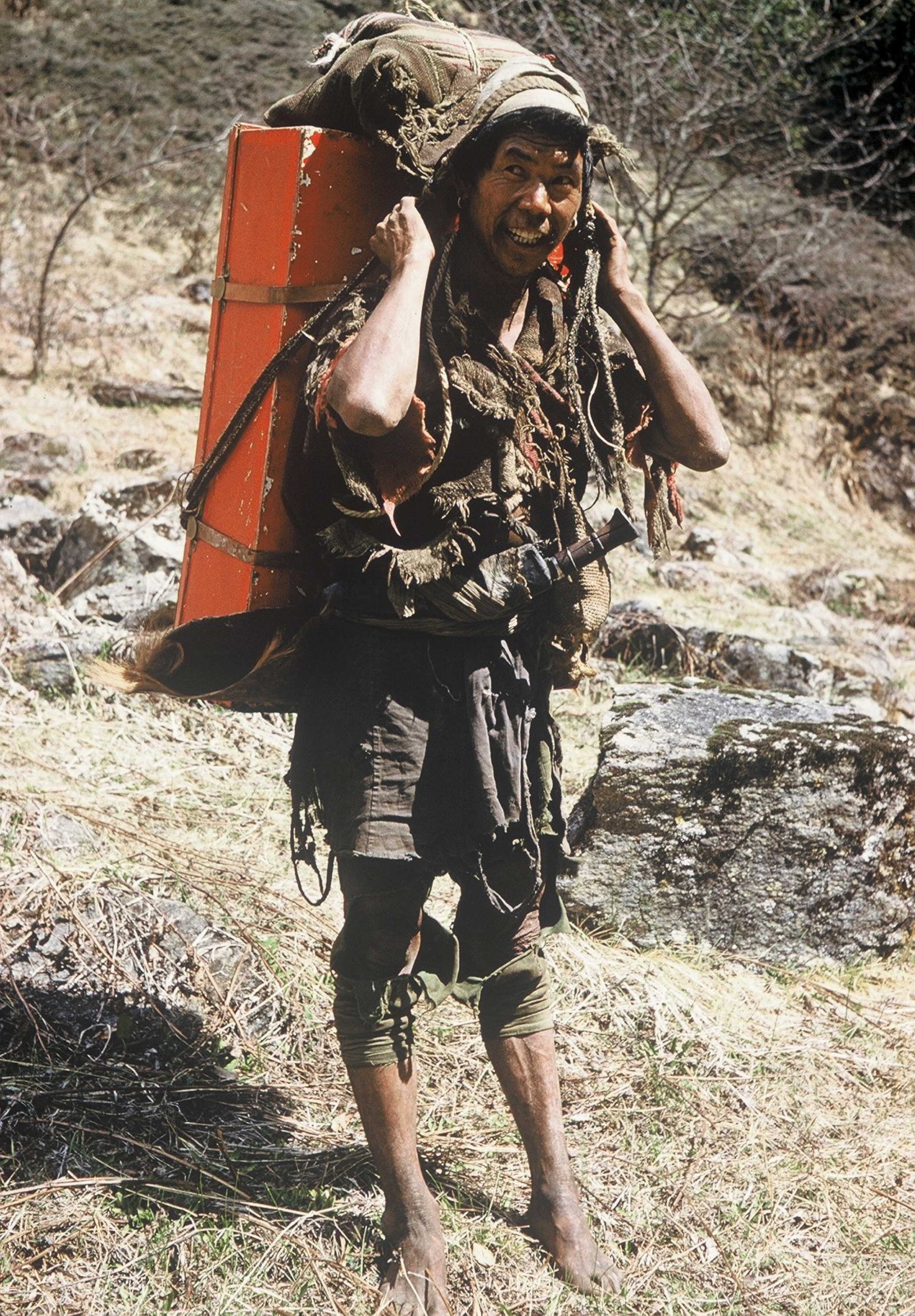

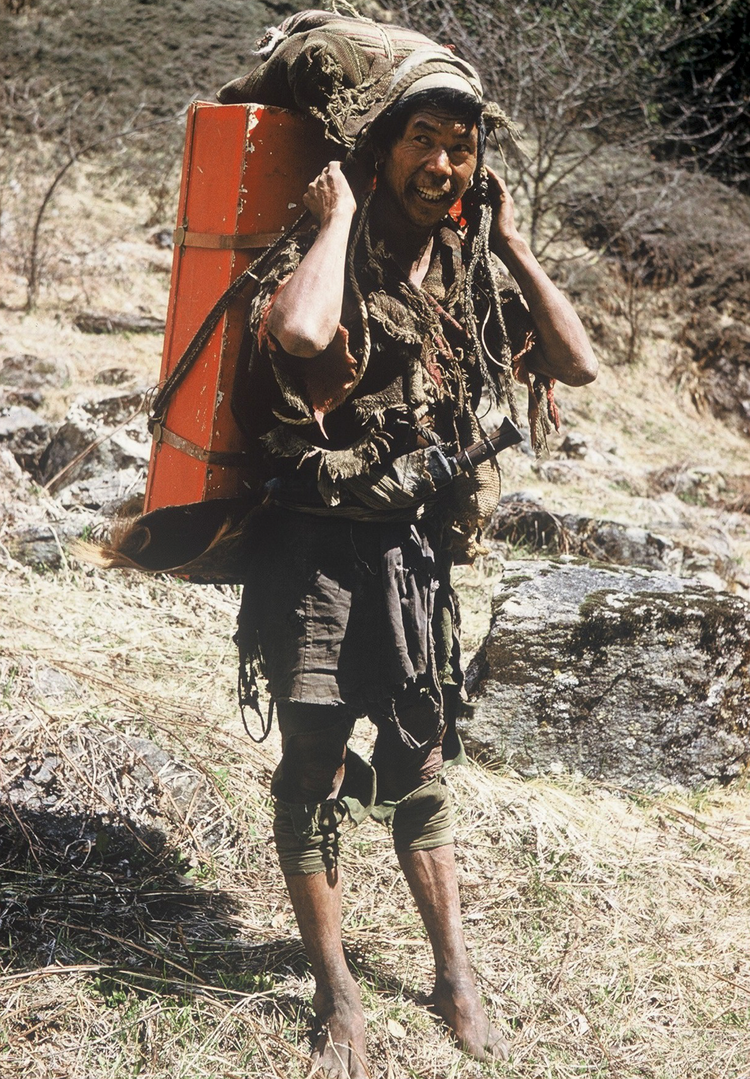

Jo: Yes—luckily Barbara was an expert sewer, so she made the sleeping bags and the tents, as well as anoraks for the Ladakhi porters in the Indian Himalayas. We were always short of money, so we basically did our own thing.

Sam: Reading your book it’s pretty remarkable how straightforward your drive across the Himalayas is… apart from the punctures.

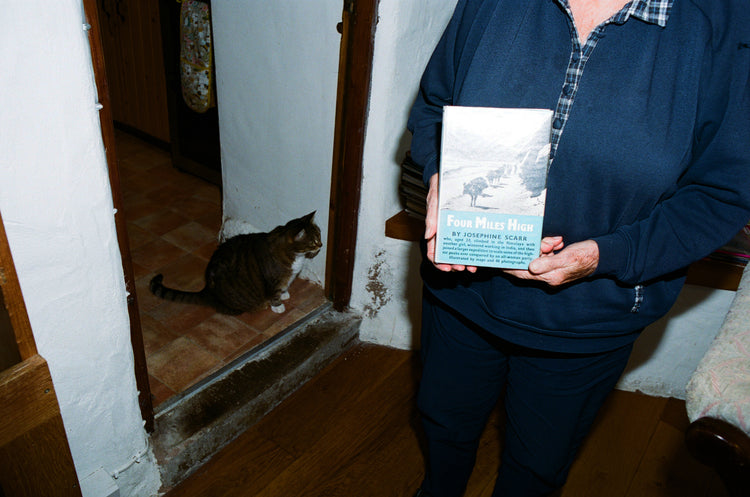

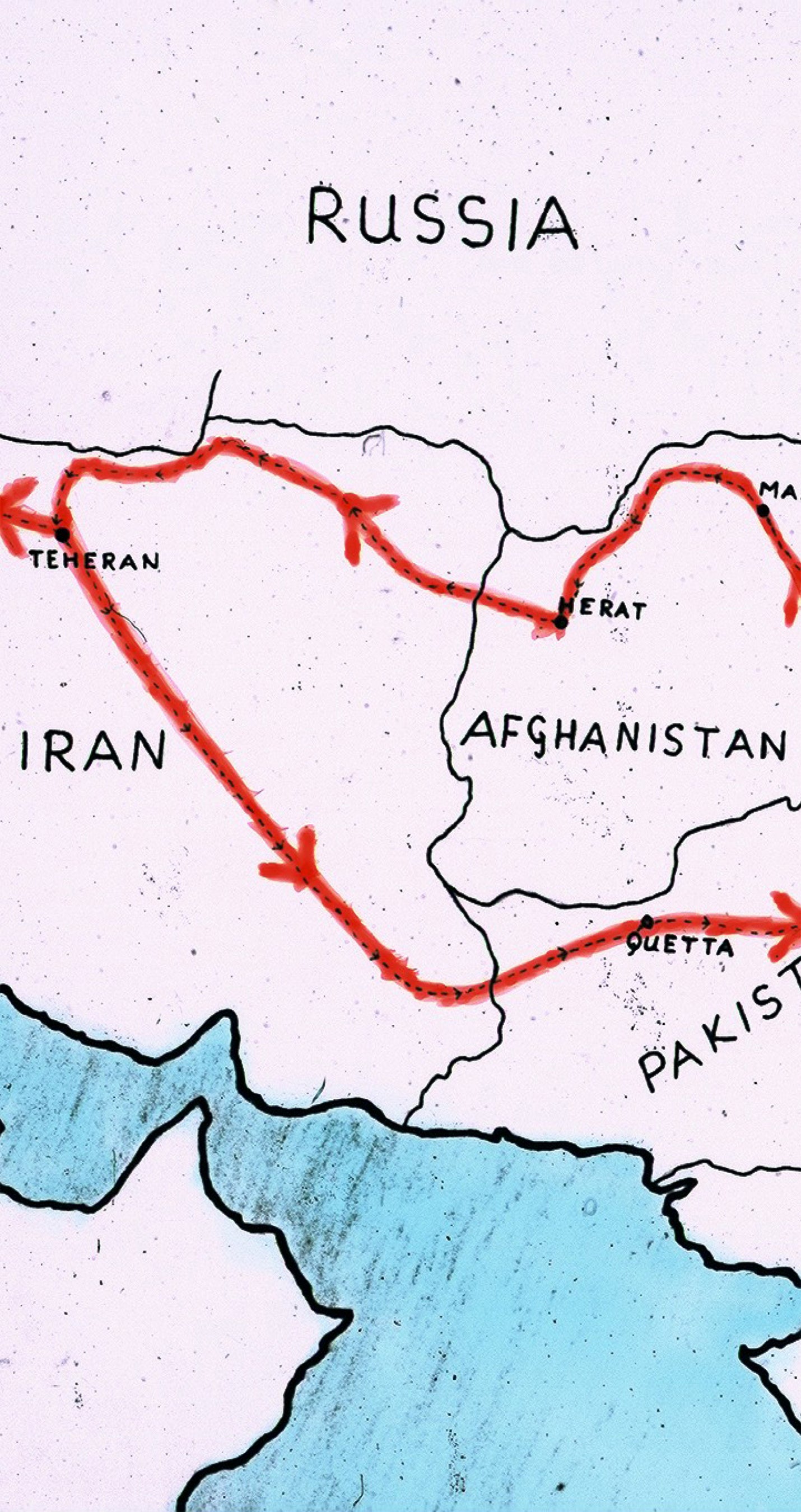

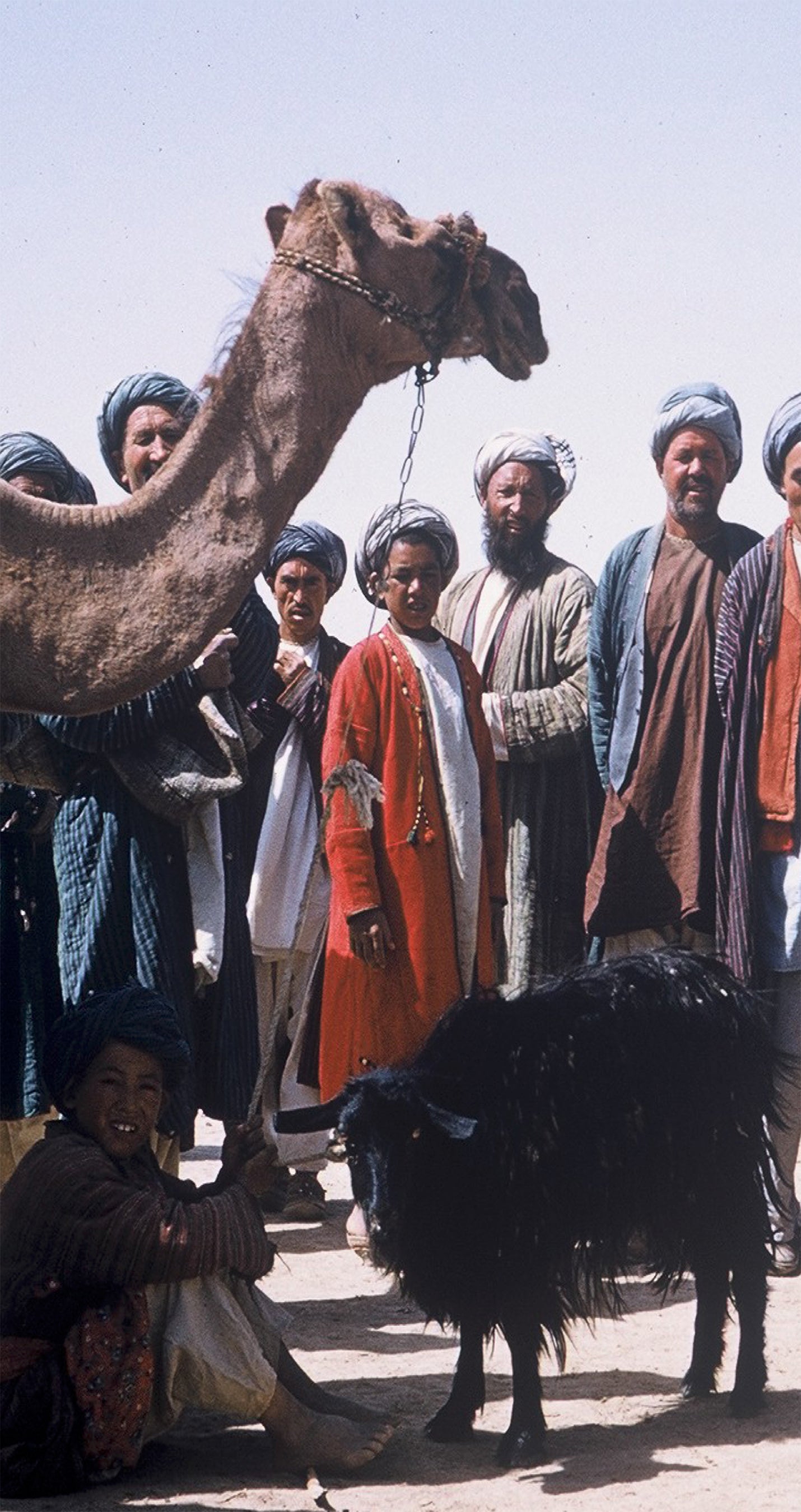

Jo: We had an awful lot of punctures—50 of them. The roads in Iran were awful because there were camel nails everywhere. At one time I was lying underneath using the jack, wearing my jeans and a shirt and emerged to find a whole group of guys standing around us. One of them spoke a bit of English, and he looked at Barbara and me and said, “Are you men or women?” He just couldn’t imagine that women were in that situation.

I remember when we were driving back we did feel threatened at one point. We didn’t take guns with us on the trip as we thought it could have been too dangerous if they got turned on us, but we did have our ice axes. In Afghanistan a guy came up to us talking quickly and we felt a bit threatened, so we got our axes at the ready and when he came back it turned out he had been asking us if we’d like some plums—he’d brought a basket of them for us.

On our drive we did encounter one unexpected difficulty. In Afghanistan going up a mountain pass the zig zags were so sharp that the Land Rover wouldn’t go around without doing a three-point turn. One of the scariest things was in Kashmir when we ran out of petrol on this very windy mountain road—we’d gone over one of these horrible bridges with only a narrow plank for each wheel—and I had to reverse back over that. But we made it.

Sam: How was it when you finally got to the Himalayas? What was the reality of climbing there compared to say Wales or the Lakes?

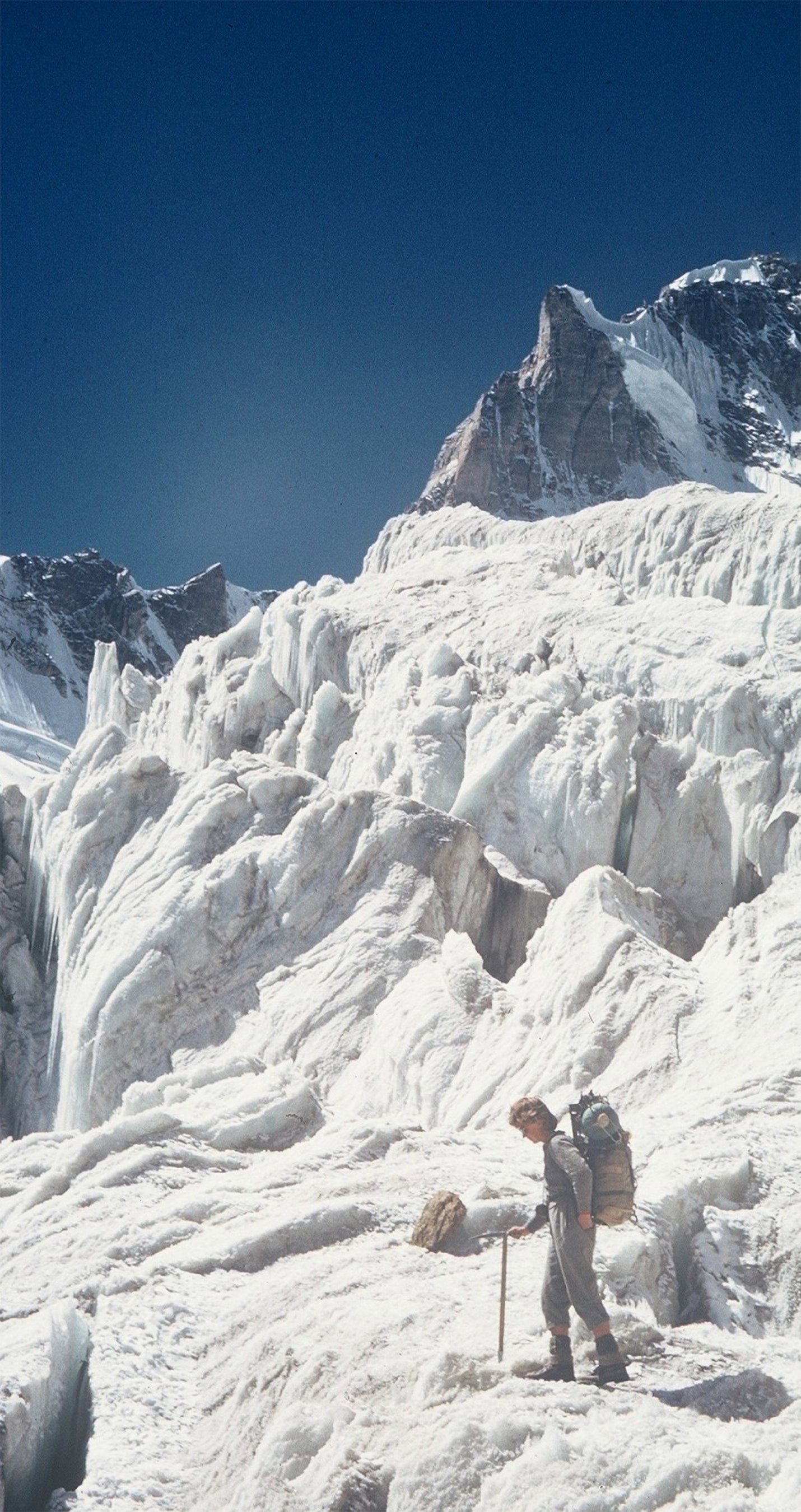

Jo: Because we laid down where we climbed and what we did, I don’t remember ever getting scared. If we chose the wrong route, we just went back again. We were very careful because we knew there was no possibility of rescue. The highlight of the Himalayan climbing was going onto glaciers and into valleys that no human being had ever been on before.

We went off the main glacier and into Kullu—surrounded by mountains of about 20,000 feet—and neither the locals or any other climbers had ever been there before. There we climbed peaks nobody had ever seen before, never mind climbed.

Sam: And after all that you went to Nepal didn’t you?

Jo: We first drove out to the Indian Himalayas just before the winter snows for about six weeks—then we went to Delhi and got jobs teaching at an international pre-school, which was the hardest job I’ve ever done—it was an outdoor school so you had to make sure the children didn’t wander off.

Then in the spring we joined another group to go into North West Nepal. It was a three week walk-in because there were no roads, and there was no contact with the outside world because there was no radio or anything. We were very much on our own. Another climber, John Tyson, had tried to get there before, but he hadn’t managed to reach the middle of the range because he’d come up against waterfalls, so we were the first foreign party to go into this range of mountains. We camped in a valley at 14,000 feet and there were mountains all around—so we just climbed everything for about six weeks. We had sherpas with us, so we made sure that every sherpa got to at least one summit first.

One of the most exciting things was abseiling down into a valley that not even the locals had been into before—because at the bottom there was a waterfall which you couldn’t get back up. It was fantastic—we really felt like we were exploring and putting something on the record which wasn’t already there. I was fulfilling my ambition of discovery.

And then we had a wonderful walk-out by a different route by Annapurna and Dhaulagiri, and then we took a flight from Pokhara to Kathmandu. At that stage Pokhara airport was just a grassy field with cattle grazing there—they’d wait until they heard a plane in the sky and then they’d push all the cattle off the field. I remember the pilot wanted me to fly the plane, and sat me in the pilot’s seat. When I saw the mountains coming up I said, “Please take over!” It was crazy. It was a different world.

Sam: After all this you became an archaeologist. Did that come from a similar desire to discover new things?

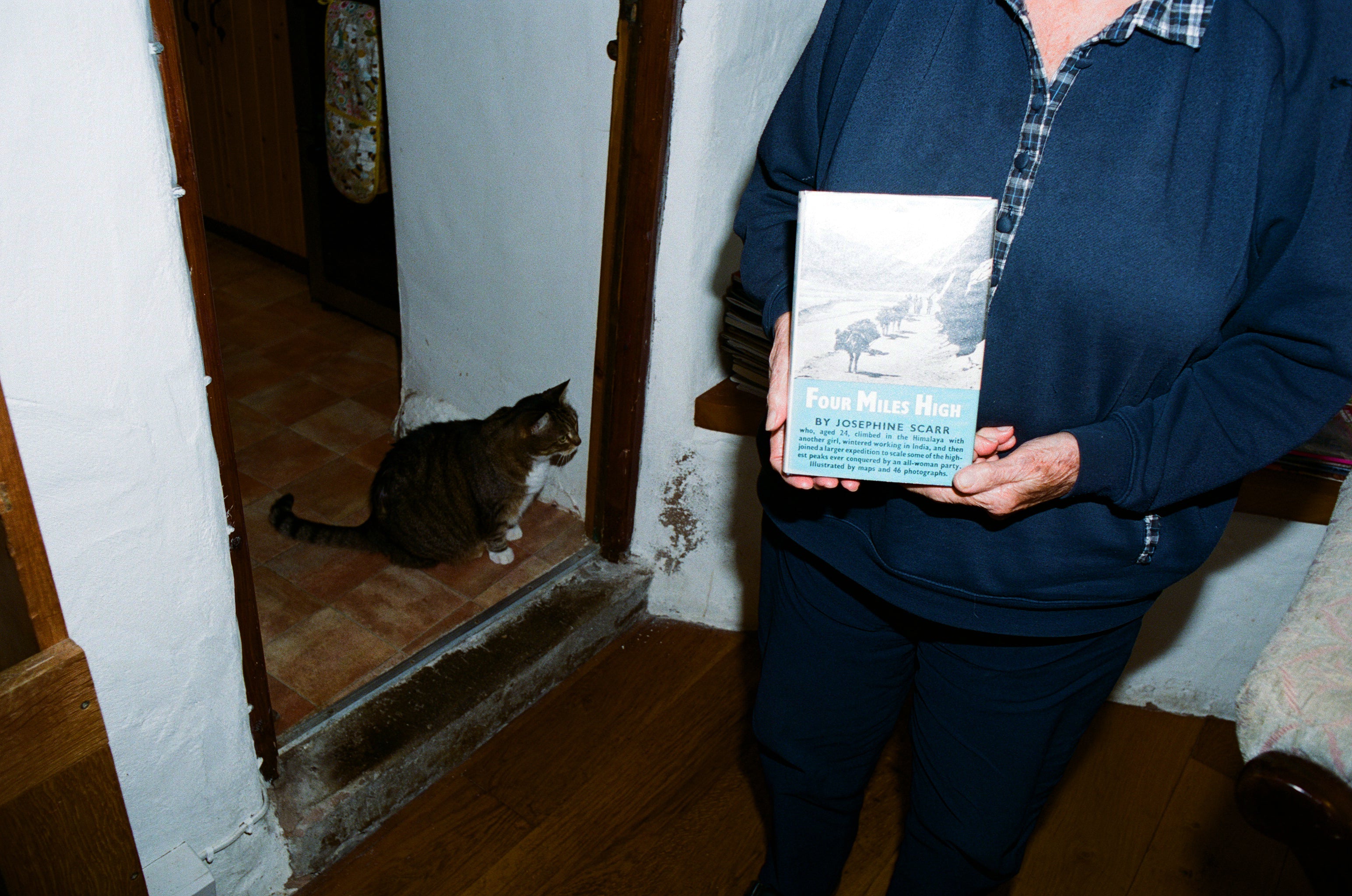

Jo: I think so, yes. I didn’t really know what to do when the expedition came to an end. The others either had children or jobs to go back to, but I didn’t because I hadn’t thought that far ahead. So for almost a year I wrote the book Four Miles High from the detailed diary I’d made on the expeditions. I then went around doing lectures about the expedition—but after that it was the question of ‘what next?’ I wanted to go climbing in New Zealand, and I found that the way to do it was to become a ten pound Pom.

Sam: What’s that?

Jo: You had to be under 40 and you had to be able to make a living, and they’d give you a chest X-Ray to make sure you didn’t have TB, and then for ten pounds you could go to Australia. From there I did the climbing in New Zealand, which I loved, but what had happened meanwhile was that I got a job at the university in Canberra, and from there I got very interested in Australian archaeology and Aboriginal things.

I turned my masters into a PHD and got totally involved in Australian archaeology. It was most exciting because I was given a huge chunk of South East Australia where no archaeologist had ever worked, and I was told to go and find out what was there. It was fabulous—again, it was discovery. And in those days, when you did a PHD, you had to write it up as a book—my book was called The Moth Hunters. I chose to do the archaeology of the Snowy Mountains—and I could even do some of my research on skis, as I’d go up to see if the moths had begun their migration to the mountains yet.

Sam: Where do moths come into this?

Jo: They were a very important insect for the Aborigines—they’d go up there and do ceremonies and live off moths for months. In fact, when I launched the book, we had a wine and moth party and I provided roasted moths on little canapes.

Sam: What does a moth taste like?

Jo: Like a roast chestnut. You build a fire on a rocky slab on the top of a mountain—the mountains there are about 6,0000 feet or so—and you collect the moths which are on the walls of the rock crevices—scoop them down off the wall into a container. They’re alive, but they’re doing the equivalent of hibernation—aestivating. You dump them on a heated rock and you roast them for a minute or two, turn them over with a stick, and then you winnow them by lifting them up with a stick… and then you eat them. I always used to keep roasted moths in my freezer so I could offer them to archaeologists.

Sam: Looking back at all these expeditions and adventures—what stands out as a highlight? What are you proudest of with all this?

Jo: I think with mountaineering, it was setting foot on a glacier that no human being had ever been on before. It wasn’t so much the rock climbing, as I was always a bit pushed on that. And then with archaeology I was given the Australian equivalent of an MBE in 2019—that means I can put AM at the end of my name. My three children were there, and I think that was the happiest day of my life—it brought it full circle.

Sam: Most people just dream of adventures like yours—what do you think set you apart in actually going on them?

Jo: I think, again, it was from reading the stories—reading all those adventure books I knew I didn’t want an office job. I was really looking to see how I could spend my life.

Nigel: I’m going to interject something in answer to that question… it's because she’s bloody stubborn.

Jo: I don’t give up. If I were to write my autobiography, I’d call it A Fortunate Life. Unfortunately there’s already a book in Australia with that title. But I feel I’ve been fortunate—I’ve had good health and I’ve survived various risky situations. I’ve always taken care, but there’s a lot of luck involved—I’ve been one of the lucky ones.

Thanks to Sam & Josh for the interview and of course, Jo and Nigel for the stories, tea, and biscuits.